කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය République démocratique du Congo (ප්රංශ) | |

|---|---|

| උද්යෝග පාඨය: "Justice – Paix – Travail" (ප්රංශ) "යුක්තිය - සාමය - වැඩ" | |

| ජාතික ගීය: Debout Congolais (ප්රංශ) "නැඟිටින්න, කොංගෝ" | |

| අගනුවර සහ විශාලතම නගරය | කිංෂාසා 4°19′S 15°19′E / 4.317°S 15.317°E |

| නිල භාෂා(ව) | ප්රංශ භාෂාව |

| පිළිගත් ජාතික භාෂා(ව) |

|

| ආගම (2021)[1] |

|

| ජාති නාම(ය) | කොංගෝ ජාතික |

| රජය | ඒකීය, අර්ධ ජනාධිපති, ජනරජය |

• ජනාධිපති | ෆීලික්ස් ෂිසෙකේඩි |

• අගමැති | සාමා ලුකොන්ඩේ |

| ව්යවස්ථාදායකය | පාර්ලිමේන්තුව |

| සෙනෙට් සභාව | |

| ජාතික සභාව | |

| පිහිටුවීම | |

• යටත් විජිතයක් බවට පත් වීම | 1879 නොවැම්බර් 17 |

| 1885 ජූලි 1 | |

| 1908 නොවැම්බර් 15 | |

• බෙල්ජියම වෙතින් නිදහස | 1960 ජූනි 30[2] |

• එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවිධානයට ඇතුළත් කර ගැනීම | 1960 සැප්තැම්බර් 20 |

• කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ලෙස නම් කිරීම | 1964 අගෝස්තු 1 |

• සයිරේ ජනරජය | 1971 ඔක්තෝබර් 27 |

• පළමු කොංගෝ යුද්ධය | 1997 මැයි 17 |

• වත්මන් ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව | 2006 පෙබරවාරි 18 |

| වර්ග ප්රමාණය | |

• සම්පූර්ණ | 2,345,409 km2 (905,567 sq mi) (11 වෙනි) |

• ජලය (%) | 3.32 |

| ජනගහණය | |

• 2023 ඇස්තමේන්තුව | 111,859,928[3] (14 වෙනි) |

• ජන ඝණත්වය | 46.3/km2 (119.9/sq mi) |

| දදේනි (ක්රශසා) | 2022 ඇස්තමේන්තුව |

• සම්පූර්ණ | |

• ඒක පුද්ගල | |

| දදේනි (නාමික) | 2022 ඇස්තමේන්තුව |

• සම්පූර්ණ | |

• ඒක පුද්ගල | |

| ගිනි (2012) | 42.1[5] මධ්යම |

| මාසද (2021) | 0.479[6] පහළ · 179 වෙනි |

| ව්යවහාර මුදල | කොංගෝ ෆ්රෑන්ක් (CDF) |

| වේලා කලාපය | UTC+1 to +2 (බටහිර අප්රිකානු වේලාව (WAT) සහ මධ්යම අප්රිකානු වේලාව (CAT)) |

| දින ආකෘති | දිදි/මාමා/වවවව |

| රිය ධාවන මං තීරුව | දකුණ |

| ඇමතුම් කේතය | +243 |

| ISO 3166 code | CD |

| අන්තර්ජාල TLD | .cd |

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය (DRC), කොංගෝ-කින්ෂාසා ලෙසද හැඳින්වේ, මධ්යම අප්රිකාවේ පිහිටි රටකි. භූමි ප්රමාණය අනුව, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය අප්රිකාවේ දෙවන විශාලතම රට වන අතර ලෝකයේ 11 වන විශාලතම රට වේ. මිලියන 112 ක පමණ ජනගහනයක් සිටින කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ලෝකයේ නිල වශයෙන් ෆ්රැන්කෝෆෝන් (ප්රංශ භාෂාව) භාවිතා කරන වැඩිම ජනගහනයක් සහිත රට වේ. ජාතික අගනුවර සහ විශාලතම නගරය කිංෂාසා වන අතර එය ආර්ථික මධ්යස්ථානය ද වේ. රට කොංගෝ ජනරජය, මධ්යම අප්රිකානු ජනරජය, දකුණු සුඩානය, උගන්ඩාව, රුවන්ඩාව, බුරුන්ඩි, ටැන්සානියාව (ටැංගනිකා විල හරහා), සැම්බියාව, ඇන්ගෝලාව, කැබින්ඩා (ඇන්ගෝලාවේ ප්රධාන භූමියෙන් පිටත පිහිටා ඇති) සහ දකුණු අත්ලාන්තික් සාගරයෙන් මායිම් වේ.

කොංගෝ ද්රෝණිය කේන්ද්ර කර ගනිමින්, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි භූමි ප්රදේශය ප්රථමයෙන් මධ්යම අප්රිකානු ආහාර සොයන්නන් විසින් වසර 90,000 කට පමණ පෙර වාසය කරන ලද අතර වසර 3,000 කට පමණ පෙර බන්ටු ප්රසාරණයෙන් ළඟා විය.[7] බටහිරින්, කොංගෝ රාජධානිය 14 සිට 19 වන සියවස දක්වා කොංගෝ නදියේ මුඛය වටා පාලනය කළේය. ඊසාන දෙසින්, මධ්යයේ සහ නැඟෙනහිර දෙසින්, අසන්ඩේ, ලුබා සහ ලුන්ඩා රාජධානි 16 වන සහ 17 වන සියවසේ සිට 19 වන සියවස දක්වා පාලනය විය. බෙල්ජියමේ දෙවන ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් රජු 1885 දී යුරෝපයේ යටත් විජිත ජාතීන්ගෙන් කොංගෝ භූමියේ අයිතිය විධිමත් ලෙස ලබා ගත් අතර එම ඉඩම ඔහුගේ පෞද්ගලික දේපළක් ලෙස ප්රකාශයට පත් කර එය කොංගෝ නිදහස් රාජ්යය ලෙස නම් කළේය. 1885 සිට 1908 දක්වා, ඔහුගේ යටත් විජිත හමුදාව රබර් නිෂ්පාදනය කිරීමට ප්රාදේශීය ජනතාවට බල කළ අතර පුලුල්ව පැතිරුණු කුරිරුකම් සිදු කළේය. 1908 දී ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් විසින් බෙල්ජියම් යටත් විජිතයක් බවට පත් වූ භූමිය පවරා දුන්නේය.

කොංගෝව 1960 ජූනි 30 වන දින බෙල්ජියමෙන් නිදහස ලබා ගත් අතර, බෙදුම්වාදී ව්යාපාර මාලාවකට, අගමැති පැට්රිස් ලුමුම්බා ඝාතනයට සහ 1965 කුමන්ත්රණයකින් මොබුටු සෙසේ සෙකෝ විසින් බලය අල්ලා ගැනීමට වහාම මුහුණ දෙන ලදී. මොබුටු 1971 දී රට සයිරේ නම් කළ අතර 1997 දී පළමු කොංගෝ යුද්ධයෙන් ඔහු පෙරලා දමන තෙක් දරුණු පුද්ගලවාදී ආඥාදායකත්වයක් පැනවීය. පසුව රට එහි නම වෙනස් කර ඇති අතර 1998 සිට 2003 දක්වා දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධයට මුහුණ දුන් අතර, එහි ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස මිලියන 5.4 ක ජනතාවක් මිය ගියහ.[8][9][10][11] 2001 සිට 2019 දක්වා රට පාලනය කළ ජනාධිපති ජෝසප් කබිලා යටතේ යුද්ධය අවසන් වූ අතර, ඔහු යටතේ රට තුළ මානව හිමිකම් දුර්වලව පැවති අතර බලහත්කාරයෙන් අතුරුදහන් කිරීම්, වධහිංසා පැමිණවීම්, අත්තනෝමතික ලෙස සිරගත කිරීම සහ සිවිල් නිදහස සීමා කිරීම වැනි නිරන්තර අපයෝජනයන් ඇතුළත් විය.[12] 2018 මහ මැතිවරණයෙන් පසුව, නිදහසෙන් පසු රටේ ප්රථම සාමකාමී බල සංක්රාන්තියේදී, කබිලාගෙන් පසු ජනාධිපති ලෙස පත් වූයේ එතැන් සිට ජනාධිපති ලෙස සේවය කළ ෆීලික්ස් ෂිසෙකේඩි විසිනි.[13] 2015 සිට, නැගෙනහිර කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය කිවු හි අඛණ්ඩ හමුදා ගැටුමක ස්ථානය විය.

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ස්වභාවික සම්පත්වලින් අතිශයින් පොහොසත් නමුත් දේශපාලන අස්ථාවරත්වය, යටිතල පහසුකම් හිඟකම, දූෂණය සහ සියවස් ගණනාවක් වාණිජ සහ යටත් විජිත නිස්සාරණය සහ සූරාකෑම යන දෙඅංශයෙන්ම පීඩා විඳිමින්, වසර 60කට වැඩි නිදහසකින් පසුව, සුළු වශයෙන් පුළුල් සංවර්ධනයක් සහිතව පවතී.[14] කිංෂාසා අගනුවරට අමතරව, ඊළඟ විශාලතම නගර දෙක වන ලුබුම්බෂි සහ ම්බුජි-මයි යන දෙකම පතල් නගර වේ. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි විශාලතම අපනයනය පිරිපහදු නොකල ඛනිජ වන අතර, චීනය 2019 දී එහි අපනයනවලින් 50% කට වඩා ලබා ගනී. 2021 දී, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි මානව සංවර්ධන මට්ටම මානව සංවර්ධන දර්ශකයට අනුව රටවල් 191 න් 179 වන ස්ථානයට පත් වූ අතර එය අවම සංවර්ධිත රටක් ලෙස වර්ගීකරණය කර ඇත.[15] 2018 වන විට, දශක දෙකක විවිධ සිවිල් යුද්ධ සහ අඛණ්ඩ අභ්යන්තර ගැටුම් වලින් පසුව, 600,000 පමණ කොංගෝ සරණාගතයින් තවමත් අසල්වැසි රටවල ජීවත් වේ.[16] ළමුන් මිලියන දෙකක් සාගින්නෙන් පෙළීමේ අවදානමක් ඇති අතර, සටන් නිසා මිලියන 4.5 ක ජනතාවක් අවතැන් වී ඇත.[17] රට එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවිධානය, නොබැඳි ව්යාපාරය, අප්රිකානු සංගමය, COMESA, දකුණු අප්රිකානු සංවර්ධන ප්රජාව, ජාත්යන්තර සංවිධානයේ ඩි ලා ෆ්රැන්කොෆෝනි සහ මධ්යම අප්රිකානු රාජ්යවල ආර්ථික ප්රජාවේ සාමාජිකයෙකි.

නිරුක්තිය

[සංස්කරණය]කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය නම් කර ඇත්තේ රට හරහා ගලා යන කොංගෝ නදිය අනුව ය. කොංගෝ ගඟ ලෝකයේ ගැඹුරුම ගංගාව වන අතර පිටකිරීමේදී ලෝකයේ තුන්වන විශාලතම ගංගාව වේ. 1876 දී බෙල්ජියමේ II ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් රජු විසින් පිහිටුවන ලද ඉහළ කොංගෝව පිළිබඳ අධ්යයනය සඳහා වූ කමිටුව (Comité d'études du haut Congo) සහ 1879 දී ඔහු විසින් පිහිටුවන ලද කොංගෝ ජාත්යන්තර සංගමය ද නම් කරන ලද්දේ ගගේ නමිනි.[18]

කොංගෝ ගඟ මුල් යුරෝපීය නාවිකයින් විසින් නම් කරන ලද්දේ 16 වන සියවසේදී කොන්ගෝ රාජධානිය සහ එහි බන්ටු වැසියන් වන කොංගෝ ජනයා ඔවුන් හමු වූ විට ය.[19][20] කොංගෝ යන වචනය පැමිණෙන්නේ කොංගෝ භාෂාවෙන් (කිකොංගෝ ලෙසද හැඳින්වේ). ඇමරිකානු ලේඛක සැමුවෙල් හෙන්රි නෙල්සන්ට අනුව: "'කොන්ගෝ' යන වචනයම මහජන රැස්වීමක් අඟවන අතර එය කොංගා මූලය වන 'රැස් කිරීම' මත පදනම් වූවක් විය හැකිය."[21] කොංගෝ ජනයාගේ නූතන නාමය බකොංගෝ 20 වැනි සියවසේ මුල් භාගයේදී හඳුන්වා දෙන ලදී.

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය අතීතයේ දී, කාලානුක්රමික අනුපිළිවෙල අනුව, කොංගෝ නිදහස් රාජ්යය, බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝව, කොංගෝ ජනරජය-ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්විල් ජනරජය, කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සහ සයිරේ ජනරජය ලෙස හැඳින්වේ. වර්තමාන නම කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය.

නිදහස ලබන විට, රට කොංගෝ-ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්විල් ජනරජය ලෙස නම් කරන ලද්දේ එහි අසල්වැසි කොංගෝ-බ්රසාවිල් ජනරජයෙන් වෙන්කර හඳුනා ගැනීම සඳහා ය. 1964 අගෝස්තු 1 වන දින ලුලුබුර්ග් ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව ප්රකාශයට පත් කිරීමත් සමඟ රට කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය බවට පත් වූ නමුත් 1971 ඔක්තෝම්බර් 27 වන දින ජනාධිපති මොබුටු සේසේ සෙකෝ විසින් සයරේ (කොංගෝ ගඟේ අතීත නාමය) ලෙස නම් කරන ලදී.[22]

සයරේ යන වචනය කිකොංගෝ වචනයක් වන nzadi ("ගංගාව"), nzadi o nzere ("ගංගා ගිලින ගංගා") හි බිදී ආ පෘතුගීසි අනුවර්තනයකි.[23][24][25] 16 වන සහ 17 වන සියවස් වලදී මෙම ගංගාව සයරේ ලෙස හඳුන්වන ලදී. 18 වන ශතවර්ෂයේ ඉංග්රීසි භාවිතයේදී කොංගෝව යන නම ක්රමයෙන් ප්රතිස්ථාපනය වී ඇති බව පෙනේ, 19 වන සියවසේ සාහිත්යයේ කොංගෝ යනු වඩාත් කැමති ඉංග්රීසි නාමයයි, නමුත් ස්වදේශිකයන් (එනම් පෘතුගීසි ව්යුත්පන්නයෙන් ව්යුත්පන්න වූ) නම ලෙස සයිරේ වෙත යොමු කිරීම් බහුලව පැවතුනි.[26]

1992 දී ස්වෛරී ජාතික සම්මේලනය රටේ නම "කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය" ලෙස වෙනස් කිරීමට ඡන්දය ප්රකාශ කළ නමුත් වෙනසක් සිදු නොවීය.[27] 1997 දී මොබුටු පෙරලා දැමූ විට ජනාධිපති ලෝරන්ට්-ඩේසිරේ කබිලා විසින් රටේ නම පසුව ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය කරන ලදී.[28] එය අසල්වැසි කොංගෝ ජනරජයෙන් වෙන්කර හඳුනා ගැනීම සඳහා, එය සමහර විට කොංගෝ (කින්ෂාසා), කොංගෝ-කින්ෂාසා හෝ බිග් කොන්ගෝ ලෙස හැඳින්වේ. එහි නම සමහර විට DR කොන්ගෝ, DRC, ලෙසද කෙටි වේ.[29] the DROC and RDC (ප්රංශ භාෂාවෙන්).[29]

ඉතිහාසය

[සංස්කරණය]බන්ටු ව්යාප්තියට පෙර, කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයෙන් සමන්විත භූමි ප්රදේශය මධ්යම අප්රිකාවේ පැරණිතම ජනාවාස වූ කණ්ඩායම් වන ම්බුටි ජනයාගේ නිවහන විය. නිවර්තන වනාන්තරවල භූ දර්ශනය සහ තෙත් සමක දේශගුණය කලාපීය ජනගහනය අඩු මට්ටමක තබා දියුණු සමාජ පිහිටුවීම වැළැක්විය. ඔවුන්ගේ දඩයම් එකතු කිරීමේ සංස්කෘතියේ නටබුන් බොහොමයක් වර්තමානය තුළ පවතී.

මුල් ඉතිහාසය

[සංස්කරණය]

දැනට කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ලෙස හඳුන්වන භූගෝලීය ප්රදේශය මීට වසර 90,000කට පෙර ජනාකීර්ණ විය.[30][31]

බන්ටු ජනයා ක්රි.පූ පළමු සහස්රයේ යම් අවස්ථාවක දී මධ්යම අප්රිකාවට ළඟා වූ අතර පසුව ක්රමයෙන් දකුණට ව්යාප්ත වීමට පටන් ගත්හ. එඬේර පාලනය සහ යකඩ යුගයේ ශිල්පීය ක්රම අනුගමනය කිරීමෙන් ඔවුන්ගේ ප්රචාරණය වේගවත් විය. දකුණේ සහ නිරිතදිග ප්රදේශවල ජීවත් වූ මිනිසුන් ආහාර සොයන කණ්ඩායම් වූ අතර, ඔවුන්ගේ තාක්ෂණයට ලෝහ තාක්ෂණයන් අවම වශයෙන් භාවිතා කිරීම පමණක් ඇතුළත් විය. මෙම කාලය තුළ ලෝහ මෙවලම් සංවර්ධනය කෘෂිකර්මාන්තයේ විප්ලවීය වෙනසක් ඇති කළේය. මෙය නැඟෙනහිර සහ ගිනිකොන දෙසින් දඩයම්කරුවන්ගේ කණ්ඩායම් අවතැන් වීමට හේතු විය. බන්ටු ව්යාප්තියේ අවසාන රැල්ල 10 වන සියවස වන විට සම්පූර්ණ වූ අතර, ඉන් අනතුරුව බන්ටු රාජධානි පිහිටුවීමෙන් පසු, වැඩිවන ජනගහණයෙන්, වහලුන්, ලුණු, යකඩ සහ තඹ වලින් වැඩි වශයෙන් වෙළඳාම් කළ සංකීර්ණ දේශීය, ප්රාදේශීය සහ විදේශීය වාණිජ ජාලයන් ඉක්මනින්ම හැකි විය.

කොංගෝ නිදහස් රාජ්යය (1877–1908)

[සංස්කරණය]

බෙල්ජියම් ගවේෂණය සහ පරිපාලනය 1870 සිට 1920 දක්වා සිදු විය. එය මුලින්ම මෙහෙයවනු ලැබුවේ බෙල්ජියමේ දෙවන ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් රජුගේ අනුග්රහය යටතේ ඔහුගේ ගවේෂණ කටයුතු සිදු කළ හෙන්රි මෝර්ටන් ස්ටැන්ලි විසිනි. ප්රධාන වශයෙන් ස්ටැන්ලි හොඳින් හඳුනන කුප්රකට ටිප්පු ටිප් වැනි අරාබි-ස්වාහීලී වහල් වෙළෙන්දන්ගේ නිරන්තර වහල් වැටලීම් හේතුවෙන් පූර්ව යටත් විජිත කොංගෝවේ නැගෙනහිර ප්රදේශ දැඩි ලෙස කඩාකප්පල් විය.[32]

කොංගෝව යටත් විජිතයක් බවට පත් විය යුතු දේ ගැන ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්ට නිර්මාණ තිබුණා.[33] සාකච්ඡා අනුප්රාප්තියක දී, ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්, ජාත්යන්තර අප්රිකානු සංගමයේ පෙරටුගාමී සංවිධානයේ සභාපති ලෙස මානුෂීය අරමුණු ප්රකාශ කරමින්, ඇත්ත වශයෙන්ම එක් යුරෝපීය ප්රතිවාදියෙකුට එරෙහිව තවත් තරඟකරුවෙකු ලෙස ක්රීඩා කළේය.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් රජු 1885 දී බර්ලින් සමුළුවේදී කොංගෝ භූමියට නිල වශයෙන් අයිතිය ලබා ගත් අතර ඉඩම ඔහුගේ පෞද්ගලික දේපළ බවට පත් කළේය. ඔහු එය කොංගෝ නිදහස් රාජ්යය ලෙස නම් කළේය.[33] ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්ගේ පාලන තන්ත්රය වෙරළ තීරයේ සිට ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්විල් (දැන් කිංෂාසා) අගනුවර දක්වා දිවෙන දුම්රිය මාර්ගය ඉදිකිරීම වැනි විවිධ යටිතල පහසුකම් ව්යාපෘති ආරම්භ කරන ලද අතර එය නිම කිරීමට වසර අටක් ගත විය.

නිදහස් රාජ්යයේ යටත් විජිතවාදීන් රබර් නිෂ්පාදනය සඳහා දේශීය ජනගහනයට බල කළ අතර ඒ සඳහා මෝටර් රථ ව්යාප්තිය සහ රබර් ටයර් සංවර්ධනය වර්ධනය වන ජාත්යන්තර වෙළඳපොළක් නිර්මාණය කළේය. තමාට සහ තම රටට ගෞරව කිරීම සඳහා බ්රසල්ස් සහ ඔස්ටෙන්ඩ් හි ගොඩනැගිලි කිහිපයක් ඉදි කළ ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්ට රබර් අලෙවිය ධනයක් විය. රබර් කෝටා බලාත්මක කිරීම සඳහා ස්වදේශිකයන්ගේ අතපය කපා දැමීම ප්රතිපත්තියක් බවට පත් කළේය.[34]

1885-1908 කාලය තුළ, සූරාකෑමේ හා රෝගාබාධවල ප්රතිවිපාකයක් ලෙස කොංගෝ ජාතිකයන් මිලියන ගණනක් මිය ගියහ. සමහර ප්රදේශවල ජනගහනය නාටකාකාර ලෙස පහත වැටුණි - නිදි අසනීප සහ වසූරිය නිසා පහළ කොංගෝ ගඟ අවට ප්රදේශවල ජනගහනයෙන් අඩකට ආසන්න ප්රමාණයක් මිය ගිය බව ගණන් බලා ඇත.[34]

අපයෝජනයන් පිළිබඳ පුවත් පැතිරෙන්නට විය. 1904 දී, කොංගෝවේ බෝමා හි බ්රිතාන්ය කොන්සල්වරයා වන රොජර් කේස්මන්ට්, බ්රිතාන්ය රජය විසින් විමර්ශනය කිරීමට උපදෙස් දෙන ලදී. ඔහුගේ වාර්තාව, කේස්මන්ට් වාර්තාව නමින් මානුෂීය අපයෝජන චෝදනා සනාථ කළේය. බෙල්ජියම් පාර්ලිමේන්තුව ස්වාධීන විමර්ශන කොමිසමක් පිහිටුවීමට ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් II ට බල කළේය. එහි සොයාගැනීම් මගින් කේස්මන්ට්ගේ අපයෝජන වාර්තාව තහවුරු කරන ලද අතර, මෙම කාලසීමාව තුළ කොංගෝවේ ජනගහනය අඩකින් අඩු වී ඇති බව නිගමනය කළේය.[35] නිවැරදි වාර්තා නොමැති නිසා මිනිසුන් කී දෙනෙක් මිය ගියාද යන්න නිශ්චිතවම තීරණය කළ නොහැක.

බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝ (1908-1960)

[සංස්කරණය]

1908 දී, බෙල්ජියම් පාර්ලිමේන්තුව, මුලික අකමැත්තක් තිබියදීත්, ජාත්යන්තර පීඩනයට (විශේෂයෙන් එක්සත් රාජධානියෙන්) හිස නැමී II ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් රජුගෙන් නිදහස් රාජ්යය අත්පත් කර ගත්තේය.[36] 1908 ඔක්තෝබර් 18 වන දින බෙල්ජියම් පාර්ලිමේන්තුව කොංගෝව බෙල්ජියම් යටත් විජිතයක් ලෙස ඈඳා ගැනීමට පක්ෂව ඡන්දය ප්රකාශ කළේය. විධායක බලය යටත් විජිත කටයුතු පිළිබඳ බෙල්ජියම් ඇමතිවරයාට, යටත් විජිත කවුන්සිලයත් (දෙකම බ්රසල්ස්හි පිහිටා ඇත) සහාය විය. බෙල්ජියම් පාර්ලිමේන්තුව බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝව සම්බන්ධයෙන් ව්යවස්ථාදායක අධිකාරිය ක්රියාත්මක කළේය. 1923 දී යටත් විජිත අගනුවර බෝමා සිට ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්විල් දක්වා, අභ්යන්තරයට තව දුරටත් ඉහලට කිලෝ මීටර 300 (සැතපුම් 190) පමණ දුරට ගෙන ගියේය.[37]

කොංගෝ නිදහස් රාජ්යයේ සිට බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝවට සංක්රමණය වීම විවේකයක් වූ නමුත් එය විශාල අඛණ්ඩ පැවැත්මක් ද පෙන්නුම් කළේය. කොංගෝ නිදහස් රාජ්යයේ අවසන් ආණ්ඩුකාරවරයා වූ බැරන් තියෝෆිල් වාහිස් බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝවේ නිලයේ රැඳී සිටි අතර II ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්ගේ පරිපාලනයේ බහුතරය ඔහු සමඟ සිටියේය.[38] කොංගෝව සහ එහි ස්වභාවික හා ඛනිජ සම්පත් බෙල්ජියම් ආර්ථිකයට විවෘත කිරීම යටත් විජිත ව්යාප්තිය සඳහා ප්රධාන චේතනාව ලෙස පැවතුනි - කෙසේ වෙතත්, සෞඛ්ය සේවා සහ මූලික අධ්යාපනය වැනි අනෙකුත් ප්රමුඛතා සෙමෙන් වැදගත් විය.

යටත් විජිත පරිපාලකයින් භූමිය පාලනය කළ අතර ද්විත්ව නීති පද්ධතියක් පැවතුනි (යුරෝපීය අධිකරණ පද්ධතියක් සහ තවත් දේශීය අධිකරණ, tribunaux indigènes). දේශීය උසාවිවලට තිබුණේ සීමිත බලතල පමණක් වන අතර යටත් විජිත පරිපාලනයේ ස්ථිර පාලනය යටතේ පැවතුනි. බෙල්ජියම් බලධාරීන් ස්වදේශිකයන්ට කොංගෝවේ කිසිදු දේශපාලන ක්රියාකාරකමකට ඉඩ නොදුන් අතර,[39] ෆෝර්ස් පබ්ලික් කැරැල්ල මැඩපවත්වන ලදී.

බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝව ලෝක යුද්ධ දෙකට සෘජුවම සම්බන්ධ විය. පළමුවන ලෝක සංග්රාමයේදී (1914-1918), ජර්මානු නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාවේ ෆෝර්ස් පබ්ලික් සහ ජර්මානු යටත් විජිත හමුදාව අතර ආරම්භක ගැටුමක් විවෘත යුද්ධයක් බවට පත් වූයේ 1916 සහ 1917 දී ජර්මානු යටත් විජිත ප්රදේශයට ඇංග්ලෝ-බෙල්ජියම්-පෘතුගීසි ඒකාබද්ධ ආක්රමණයක් සමඟිනි. 1916 සැප්තැම්බර් මාසයේදී ජෙනරාල් චාල්ස් ටොම්බියර්ගේ නායකත්වය යටතේ දැඩි සටන් වලින් පසු ටබෝරා වෙත ගමන් කළ විට ෆෝස් පබ්ලික් කැපී පෙනෙන ජයග්රහණයක් ලබා ගත්තේය.

1918 න් පසු, බෙල්ජියම පෙරදිග ජර්මානු යටත් විජිතයක් වූ රුවන්ඩා-උරුන්ඩිට එරෙහිව ජාතීන්ගේ ලීගයක් සමඟ නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු ව්යාපාරයට ෆෝස් පබ්ලික්ගේ සහභාගීත්වය වෙනුවෙන් ත්යාග පිරිනමන ලදී. දෙවන ලෝක සංග්රාමයේදී, බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝව ලන්ඩනයේ පිටුවහල්ව සිටි බෙල්ජියම් රජයට තීරණාත්මක ආදායම් මාර්ගයක් සැපයූ අතර, ෆෝස් පබ්ලික් නැවතත් අප්රිකාවේ මිත්ර පාක්ෂික ව්යාපාරවලට සහභාගී විය. බෙල්ජියම් නිලධාරීන්ගේ අණ යටතේ බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝ හමුදා විශේෂයෙන් මේජර් ජෙනරාල් ඔගස්ටේ-එඩ්වාඩ් ගිලියාර්ට් යටතේ අසෝසා, බෝර්ටා[40] සහ සායෝ හි ඉතියෝපියාවේ ඉතාලි යටත් විජිත හමුදාවට එරෙහිව සටන් කළහ.[41]

නිදහස සහ දේශපාලන අර්බුදය (1960-1965)

[සංස්කරණය]

1960 මැයි මාසයේදී පැට්රිස් ලුමුම්බාගේ නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් ජාතිකවාදී ව්යාපාරයක් වූ ජාතික කොංගෝලා ව්යාපාරය පාර්ලිමේන්තු මැතිවරණය ජයග්රහණය කළේය. 1960 ජූනි 24 දින ලුමුම්බා කොංගෝ ජනරජයේ ප්රථම අග්රාමාත්යවරයා බවට පත් විය. පාර්ලිමේන්තුව විසින් එලායන්ස් ඩෙස් බකොන්ගෝ (ABAKO) පක්ෂයේ ජනාධිපති ලෙස ජෝසප් කසා-වුබු තේරී පත් විය. මතු වූ අනෙකුත් පක්ෂ අතරට ඇන්ටොයින් ගිසෙන්ගා විසින් නායකත්වය දුන් පාර්ටි සොලිඩෙයාර් අප්රිකන් සහ ඇල්බට් ඩෙල්වෝක්ස් සහ ලෝරන්ට් ම්බරිකෝ විසින් නායකත්වය දුන් පාර්ටි නැෂනල් ඩි පියුපිල් ඇතුළත් විය.[42]

බෙල්ජියම් කොංගෝව 1960 ජූනි 30 දින "République du Congo" (කොංගෝ ජනරජය) නමින් නිදහස ලබා ගත්තේය. අසල්වැසි ප්රංශ යටත් විජිතයක් වන මැද කොංගෝ (මොයෙන් කොංගෝ) ද නිදහස ලබා ගැනීමත් සමඟ "කොංගෝ ජනරජය" යන නම තෝරා ගත් බැවින්, එම රටවල් දෙක ඔවුන්ගේ රටේ නමට පසුව අගනුවර යොදා "කොංගෝ-ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්විල්" සහ "කොංගෝ-බ්රසාවිල්" ලෙස හැඳින්විණි.

නිදහසින් ටික කලකට පසු ෆෝස් පබ්ලික් කැරලි ගැසූ අතර, ජූලි 11 වන දින කටන්ගා පළාත (මොයිස් ෂොම්බේ විසින් මෙහෙයවනු ලැබේ) සහ දකුණු කසායි නව නායකත්වයට එරෙහිව බෙදුම්වාදී අරගලවල නිරත විය.[43][44] නිදහස ලැබීමෙන් පසු ඉතිරිව සිටි යුරෝපීයයන් 100,000 න් බොහෝ දෙනෙක් රටින් පලා ගිය අතර,[45] යුරෝපීය මිලිටරි සහ පරිපාලන ප්රභූව වෙනුවට කොංගෝ ජාතිකයන්ට මග විවර කළහ.[46] බෙදුම්වාදී ව්යාපාර මැඩලීමට උදව් ඉල්ලා ලුමුම්බා කළ ඉල්ලීම එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවිධානය ප්රතික්ෂේප කිරීමෙන් පසුව, ලුමුම්බා සෝවියට් සංගමයෙන් ආධාර ඉල්ලා සිටි අතර, ඔවුන් හමුදා සැපයුම් සහ උපදේශකයන් පිළිගෙන යවන ලදී. අගෝස්තු 23 වන දින, කොංගෝ සන්නද්ධ හමුදා දකුණු කසායි ආක්රමණය කළහ. දකුණු කසායි හි සන්නද්ධ හමුදාවන් විසින් සිදු කරන ලද සමූලඝාතන සහ රට තුළ සෝවියට් සභා සම්බන්ධ කිරීම සම්බන්ධයෙන් ඔහුට ප්රසිද්ධියේ දොස් පැවරූ කසා-වුබු විසින් 1960 සැප්තැම්බර් 5 වන දින ලුමුම්බා ධුරයෙන් පහ කරන ලදී.[47] ලුමුම්බා කසා-වුබුගේ ක්රියාව ව්යවස්ථා විරෝධී බව ප්රකාශ කළ අතර නායකයන් දෙදෙනා අතර අර්බුදයක් වර්ධනය විය.[48]

සැප්තැම්බර් 14 දින, කර්නල් ජෝසප් මොබුටු, එක්සත් ජනපදයේ සහ බෙල්ජියමේ පිටුබලය ඇතිව, ලුමුම්බා තනතුරෙන් ඉවත් කළේය. 1961 ජනවාරි 17 වන දින, ලුමුම්බා කටන්ගන් බලධාරීන්ට භාර දුන් අතර බෙල්ජියම් ප්රමුඛ කටන්ගන් හමුදා විසින් මරා දමන ලදී.[49] 2001 දී බෙල්ජියමේ පාර්ලිමේන්තුව විසින් කරන ලද පරීක්ෂණයකින් ලුමුම්බා ඝාතනයට බෙල්ජියම "සදාචාරාත්මකව වගකිව යුතු" බව සොයා ගත් අතර, ඔහුගේ මරණය සම්බන්ධයෙන් රට නිල වශයෙන් සමාව ඉල්ලා ඇත.[50]

1961 සැප්තැම්බර් 18 වන දින, සටන් විරාමයක් පිළිබඳ අඛණ්ඩ සාකච්ඡා වලදී, න්ඩෝලා අසල ගුවන් අනතුරක් හේතුවෙන්, එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ මහලේකම්ඩැග් හමර්ස්ක්ජෝල්ඩ්, මගීන් 15 දෙනා සමඟ මියයෑම අර්බුදයක් ඇති කළේය. පුලුල් ව්යාකූලත්වය සහ ව්යාකූලත්වය මධ්යයේ, තාක්ෂණවේදීන් (The Collège des commissaires généraux) විසින් තාවකාලික රජයක් මෙහෙයවන ලදී. 1963 ජනවාරි මාසයේදී එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ හමුදාවේ සහාය ඇතිව කටන්ගන් වෙන්වීම අවසන් විය. ජෝසප් ඉලියෝ, සිරිල් අදූලා සහ මොයිස් කැපෙන්ඩා ෂොම්බේගේ කෙටි කාලීන ආන්ඩු කිහිපයක් ඉක්මනින් අවසන් විය.

මේ අතර, රටේ නැගෙනහිරින්, සිම්බාස් නමින් හැඳින්වෙන සෝවියට් සහ කියුබානු පිටුබලය ලත් කැරලිකරුවන් නැගී සිටි අතර, සැලකිය යුතු භූමි ප්රමාණයක් අත්පත් කර ගනිමින් ස්ටැන්ලිවිල් හි කොමියුනිස්ට් "කොංගෝ මහජන සමූහාණ්ඩුවක්" ප්රකාශයට පත් කළහ. ප්රාණ ඇපකරුවන් සිය ගනනක් ගලවා ගැනීම සඳහා බෙල්ජියම් සහ ඇමරිකානු හමුදා විසින් සිදු කරන ලද ඩ්රැගන් රූජ් මෙහෙයුමේදී සිම්බාස් 1964 නොවැම්බර් මාසයේදී ස්ටැන්ලිවිල් වෙතින් ඉවතට තල්ලු කරන ලදී. කොංගෝ රජයේ හමුදා 1965 නොවැම්බර් වන විට සිම්බා කැරලිකරුවන් සම්පූර්ණයෙන්ම පරාජය කරන ලදී.[51]

ලුමුම්බා මීට පෙර මොබුටු නව කොංගෝ හමුදාවේ (Armée Nationale Congolaise) මාණ්ඩලික ප්රධානියා ලෙස පත් කර ඇත.[52] කසවුබු සහ ත්ෂොම්බේ අතර නායකත්ව අර්බුදයෙන් ප්රයෝජන ගනිමින්, මොබුටු කුමන්ත්රණයක් දියත් කිරීමට හමුදාව තුළ ප්රමාණවත් සහයෝගයක් ලබා ගත්තේය. 1965 මොබුටුගේ කුමන්ත්රණයට පෙර වර්ෂයේ ව්යවස්ථාපිත ජනමත විචාරණයක ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස රටේ නිල නාමය "කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය" ලෙස වෙනස් විය. 1971 දී මොබුටු නම නැවතත් "සයර් ජනරජය" ලෙස වෙනස් කරන ලදී.[53][22]

මොබුටු ආඥාදායකත්වය සහ සයිරේ (1965-1997)

[සංස්කරණය]

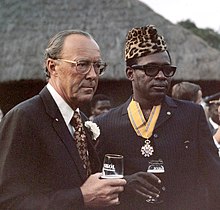

කොමියුනිස්ට්වාදයට විරුද්ධ වීම නිසා මොබුටුට එක්සත් ජනපදයේ දැඩි සහයෝගයක් ලැබුණි; ඔහුගේ පරිපාලනය අප්රිකාවේ කොමියුනිස්ට් ව්යාපාරවලට ඵලදායි ප්රතිවිරෝධයක් ලෙස සේවය කරනු ඇතැයි එක්සත් ජනපදය විශ්වාස කළේය.[54] තනි පක්ෂ ක්රමයක් ස්ථාපිත කරන ලද අතර, මොබුටු තමා රාජ්ය නායකයා ලෙස ප්රකාශ කළේය. ඔහු එකම අපේක්ෂකයා වූ මැතිවරණ වරින් වර පැවැත්වීය. සාපේක්ෂ සාමය සහ ස්ථාවරත්වය අත්පත් කරගනු ලැබුවද, මොබුටුගේ රජය දරුණු මානව හිමිකම් උල්ලංඝනය කිරීම්, දේශපාලන මර්දනය, පෞරුෂ වන්දනාව සහ දූෂණය සම්බන්ධයෙන් වැරදිකරු විය.

1967 අග භාගය වන විට මොබුටු තම දේශපාලන විරුද්ධවාදීන් සහ ප්රතිවාදීන් තම පාලන තන්ත්රයට සම්බන්ධ කර ගැනීම, ඔවුන් අත්අඩංගුවට ගැනීම හෝ වෙනත් ආකාරයකින් දේශපාලනික වශයෙන් බෙලහීන කිරීම මගින් ඔවුන්ව සාර්ථක ලෙස උදාසීන කළේය.[55] 1960 ගණන්වල අග භාගය පුරාම, මොබුටු පාලනය පවත්වා ගැනීම සඳහා කාර්යාලය තුළ සහ ඉන් පිටත ඔහුගේ රජයේ නිලධාරීන් අඛණ්ඩව මාරු කළේය. 1969 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී ජෝසෆ් කසා-වුබුගේ මරණයෙන් පළමු ජනරජයේ අක්තපත්ර ඇති කිසිවකුට ඔහුගේ පාලනයට අභියෝග කළ නොහැකි බව සහතික විය.[56] 1970 ගණන්වල මුල් භාගය වන විට, මොබුටු ප්රමුඛ අප්රිකානු ජාතියක් ලෙස සයිරේ ප්රකාශ කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළේය. ඔහු මහාද්වීපය හරහා නිතර සංචාරය කළ අතර රජය අප්රිකානු ප්රශ්න, විශේෂයෙන් දකුණු ප්රදේශයට අදාළ ප්රශ්න ගැන වඩාත් හඬ නඟා සිටියේය. සයිරේ කුඩා අප්රිකානු රාජ්යයන් කිහිපයක්, විශේෂයෙන් බුරුන්ඩි, චැඩ් සහ ටෝගෝ සමඟ අර්ධ-සේවාදායක සබඳතා ඇති කර ගත්තේය.[57]

දූෂණය කෙතරම් සුලභ වී ඇත්ද, "le mal Zairois" හෝ "Zairian sickness" යන යෙදුම,[58] දළ දූෂණය, සොරකම සහ වැරදි කළමනාකරණය යන අර්ථය ඇති අතර, මොබුටු විසින් වාර්තා කරන ලදී.[59]

ජාත්යන්තර ආධාර, බොහෝ විට ණය ආකාරයෙන්, මොබුටු පොහොසත් කළ අතර, ඔහු මාර්ග වැනි ජාතික යටිතල පහසුකම් 1960 දී පැවති දෙයින් හතරෙන් එකක් වැනි සුළු ප්රමාණයකට පිරිහීමට ඉඩ දුන්නේය.

අප්රිකානු ජාතිකවාදය සමඟ තමාව හඳුනා ගැනීමේ ව්යාපාරයක දී, 1966 ජුනි 1 සිට, මොබුටු ජාතියේ නගර නැවත නම් කළේය: ලියෝපෝල්ඩ්විල් කිංෂාසා බවට ද (රට කොංගෝ-කින්ෂාසා ලෙස හැඳින්විණි), ස්ටැන්ලිවිල් කිසන්ගානි බවට ද, එලිසබෙත්විල් ලුබුම්බාෂි බවට ද, කොක්විල්හැට්විල් ම්බණ්ඩකා බවට ද පත් විය. 1971 දී මොබුටු විසින් රට සයිරේ ජනරජය ලෙස නම් කරන ලදී,[22] වසර එකොළහකින් එහි සිව්වන නම වෙනස් වූ අතර සමස්තයක් වශයෙන් එහි හයවන නම වෙනස් විය. කොංගෝ ගඟ සයිරේ ගඟ ලෙස නම් කරන ලදී.

1970 සහ 1980 ගණන් වලදී, මොබුටුට අවස්ථා කිහිපයකදී එක්සත් ජනපදයට පැමිණෙන ලෙස ආරාධනා කරන ලදී, එක්සත් ජනපද ජනාධිපතිවරුන් වන රිචඩ් නික්සන්, රොනල්ඩ් රේගන් සහ ජෝර්ජ් එච්.ඩබ්ලිව්. බුෂ් හමුවිය.[60] සෝවියට් සංගමය විසුරුවා හැරීමෙන් පසු මොබුටු සමඟ එක්සත් ජනපද සබඳතා සිසිල් විය, ඔහු තවදුරටත් සීතල යුද්ධයේ මිතුරෙකු ලෙස අවශ්ය නොවන බව සලකනු ලැබීය. සයිරේ තුළ විරුද්ධවාදීන් ප්රතිසංස්කරණ සඳහා ඉල්ලීම් වේගවත් කළහ. 1990 දී මොබුටු විසින් තුන්වන ජනරජය ප්රකාශයට පත් කිරීමට මෙම වාතාවරණය දායක වූ අතර, එහි ව්යවස්ථාව ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ප්රතිසංස්කරණ සඳහා මග පෑදීය. ප්රතිසංස්කරණ බොහෝ දුරට අනවශ්ය දේවල් බවට පත් විය. 1997 දී සන්නද්ධ හමුදා ඔහුට පලා යාමට බල කරන තෙක් මොබුටු බලයේ දිගටම සිටියේය.[61]

1997 සැප්තැම්බර් මාසයේදී මොබුටු මොරොක්කෝවේ පිටුවහල්ව සිටියදී මිය ගියේය.[62]

මහාද්වීපික සහ සිවිල් යුද්ධ (1996-2007)

[සංස්කරණය]

1996 වන විට, රුවන්ඩා සිවිල් යුද්ධයෙන් සහ ජන සංහාරයෙන් සහ රුවන්ඩාවේ ටුට්සි නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් රජයක් බලයට පත්වීමෙන් පසුව, රුවන්ඩා හුටු මිලීෂියා හමුදා (ඉන්ටෙරහම්වේ) නැගෙනහිර සයිරේ වෙත පලා ගිය අතර රුවන්ඩාවට එරෙහි ආක්රමණ සඳහා කඳවුරු ලෙස සරණාගත කඳවුරු භාවිතා කළහ. ඔවුන් නැගෙනහිර සයිරේහි කොංගෝ වාර්ගික ටුට්සිවරුන්ට එරෙහිව උද්ඝෝෂනයක් දියත් කිරීම සඳහා සයිරියානු සන්නද්ධ හමුදාවන් සමඟ සන්ධානගත විය.[63]

පළමු කොංගෝ යුද්ධය දියත් කරමින් මොබුටු රජය පෙරලා දැමීම සඳහා රුවන්ඩා සහ උගන්ඩා හමුදාවන්ගේ සන්ධානයක් සයිරේ ආක්රමණය කළේය. ලෝරන්ට්-ඩෙසිරේ කබිලාගේ නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් සමහර විපක්ෂ නායකයින් සමඟ කොන්ගෝ විමුක්තිය සඳහා වූ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී බලවේගයන්ගේ සන්ධානය බවට පත් විය. 1997 දී මොබුටු පලා ගිය අතර කබිලා කිංෂාසා වෙත ගමන් කරමින් තමා ජනාධිපති ලෙස නම් කර රටේ නම කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය බවට පත් කළේය.[64][65]

කබිලා පසුව ඉල්ලා සිටියේ විදේශීය හමුදා හමුදා ඔවුන්ගේම රටවලට ආපසු යන ලෙසයි. රුවන්ඩා හමුදා ගෝමා වෙත පසු බැස කබිලාට එරෙහිව සටන් කිරීම සඳහා Rassemblement Congolais pour la Democratie නමින් නව ටුට්සි ප්රමුඛ කැරලිකාර හමුදා ව්යාපාරයක් දියත් කළ අතර උගන්ඩාව කොංගෝ යුද නායක ජීන් විසින් මෙහෙයවන ලද කොංගෝ විමුක්ති ව්යාපාරය නමින් කැරලිකාර ව්යාපාරයක් නිර්මාණය කිරීමට ජීන්-පියරේ බෙම්බා. උසිගන්වන ලදී.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත] රුවන්ඩා සහ උගන්ඩා හමුදා සමඟ කැරලිකාර ව්යාපාර දෙක 1998 දී කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හමුදාවට ප්රහාර එල්ල කරමින් දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධය ආරම්භ කළහ. ඇන්ගෝලා, සිම්බාබ්වේ සහ නැමීබියානු හමුදා රජයේ පාර්ශ්වයෙන් සතුරුකම්වලට ඇතුල් වූහ.

කබිලා 2001 දී ඝාතනය විය.[66] ඔහුගේ පුත් ජෝසප් කබිලා ඔහුගෙන් පසුව[67] බහුපාර්ශ්වික සාම සාකච්ඡා සඳහා කැඳවුම් කළේය. එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සාම සාධක භටයන්, MONUC, දැන් MONUSCO ලෙස හඳුන්වනු ලබන අතර, 2001 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී පැමිණියා. 2002-03 දී බෙම්බා මධ්යම අප්රිකානු ජනරජයට මැදිහත් වන ලෙස එහි හිටපු ජනාධිපති ඇන්ජ්-ෆීලික්ස් පටස්සේ ගෙන් ඉල්ලීය.[68] සාකච්ඡා සාම ගිවිසුමකට තුඩු දුන් අතර ඒ යටතේ කබිලා හිටපු කැරලිකරුවන් සමඟ බලය බෙදා ගනී. 2003 ජූනි වන විට රුවන්ඩාවේ හමුදා හැර අනෙකුත් සියලුම විදේශීය හමුදා කොංගෝවෙන් ඉවත් විය. මැතිවරණය අවසන් වනතුරු සංක්රාන්ති ආණ්ඩුවක් පිහිටුවන ලදී. ව්යවස්ථාවක් ඡන්දදායකයින් විසින් අනුමත කරන ලද අතර 2006 ජූලි 30 දින කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය එහි පළමු බහු-පක්ෂ මැතිවරණය පැවැත්වීය. 1960 න් පසු ප්රථම නිදහස් ජාතික මැතිවරණය මෙය වූ අතර, එය කලාපයේ ප්රචණ්ඩත්වයේ අවසානය සනිටුහන් කරනු ඇතැයි බොහෝ දෙනා විශ්වාස කළහ.[69] කෙසේ වෙතත්, කබිලා සහ බෙම්බා අතර මැතිවරණ ප්රතිඵල ආරවුලක් කිංෂාසා හි ඔවුන්ගේ ආධාරකරුවන් අතර ගැටුමක් බවට පත් විය. MONUC නගරය පාලනය සියතට ගත්තේය. 2006 ඔක්තෝම්බර් මාසයේදී නව මැතිවරණයක් සිදු වූ අතර එය කබිලා ජයග්රහණය කළ අතර 2006 දෙසැම්බර් මාසයේදී ඔහු ජනාධිපති ලෙස දිවුරුම් දුන්නේය.

අඛණ්ඩ ගැටුම් (2008-2018)

[සංස්කරණය]කිවු ගැටුම

[සංස්කරණය]

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදය සඳහා රැලියේ සාමාජිකයෙකු වන ලෝරන්ට් න්කුන්ඩා, හමුදාවට ඒකාබද්ධ වූ කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදය සඳහා වූ රැලියෙන් ඉවත් වන අතර, ඔහුට පක්ෂපාතී හමුදා සමඟින් ඉවත් වී, සන්නද්ධ සංවිධානයක් ආරම්භ කළ ජනතා ආරක්ෂාව සඳහා වූ ජාතික කොංග්රසය (CNDP) පිහිටුවන ලදී. 2009 මාර්තු මාසයේදී, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සහ රුවන්ඩාව අතර ගනුදෙනුවකින් පසුව, රුවන්ඩා හමුදා කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වෙත ඇතුළු වී න්කුන්ඩා අත්අඩංගුවට ගත් අතර FDLR සටන්කාමීන් පසුපස හඹා යාමට අවසර දෙන ලදී. CNDP රජය සමඟ සාම ගිවිසුමක් අත්සන් කරන ලද අතර, එහි සිරගතව සිටින සාමාජිකයින් නිදහස් කිරීම සඳහා දේශපාලන පක්ෂයක් බවට පත්වීමට සහ එහි සොල්දාදුවන් ජාතික හමුදාවට ඒකාබද්ධ කිරීමට එකඟ විය.[70] 2012 දී CNDP හි නායක බොස්කෝ නටගන්ඩා සහ ඔහුට පක්ෂපාතී හමුදා කැරලි ගසා කැරලිකාර හමුදාව මාර්තු 23 ව්යාපාරය (M23) පිහිටුවා ගත්හ. ඒ රජය ගිවිසුම කඩ කළ බව පවසමිනි.[71]

එහි ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස ඇති වූ M23 කැරැල්ලේදී, M23 2012 නොවැම්බර් මාසයේදී ගෝමා පළාත් අගනුවර අල්ලා ගත්තේය.[72][73] අසල්වැසි රටවලට, විශේෂයෙන් රුවන්ඩාවට, කැරලිකරුවන්ගේ කණ්ඩායම් සන්නද්ධ කිරීම සහ සම්පත් ලබාගැනීමට රටේ පාලනය ලබා ගැනීම සඳහා ඔවුන් රූකඩ ලෙස භාවිතා කිරීම සම්බන්ධයෙන් චෝදනා එල්ල වී ඇති අතර, එය ඔවුන් ප්රතික්ෂේප කරන චෝදනාවකි.[74][75] 2013 මාර්තු මාසයේදී එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ ආරක්ෂක කවුන්සිලය සන්නද්ධ කණ්ඩායම් උදාසීන කිරීමට එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ බලකා මැදිහත්වීම් බලකායට බලය ලබා දුන්නේය.[76] 2013 නොවැම්බර් 5 දින M23 එහි කැරැල්ල අවසන් කරන බව ප්රකාශ කළේය.[77]

මීට අමතරව, උතුරු කටන්ගා හි, ලෝරන්ට් කබිලා විසින් නිර්මාණය කරන ලද මායි-මායි විසින් කින්ෂාසා පාලනයෙන් ගිලිහී ගියේ 2013 දී ලුබුම්බාෂි පළාත් අගනුවර කෙටි කලකට ආක්රමණය කිරීමත් සමඟින් ලෝරන්ට් කබිලා විසින් කින්ෂාසා පාලනයෙන් ගිලිහී ගිය අතර පුද්ගලයන් 400,000 ක් පලා ගියහ.[78] ඉටුරි ගැටුමේ දී සහ ඉන් පිටතදී පිළිවෙළින් ලෙන්ඩු සහ හේමා ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම් නියෝජනය කරන බව කියන ජාතිකවාදී සහ ඒකාබද්ධතාවාදී පෙරමුණ සහ කොංගෝ දේශප්රේමීන්ගේ සංගමය අතර ගැටුම් ඇති විය. ඊසානදිගින්, ජෝසප් කෝනිගේ ශ්රේෂ්ඨ ප්රතිරෝධක හමුදාව 2005 දී උගන්ඩාවේ සහ දකුණු සුඩානයේ ඔවුන්ගේ මුල් කඳවුරු වලින් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වෙත ගොස් ගරඹා ජාතික වනෝද්යානයේ කඳවුරු පිහිටුවා ගත්හ.[79][80]

කොංගෝවේ යුද්ධය දෙවන ලෝක යුද්ධයෙන් පසු බිහිසුනු යුද්ධයක් ලෙස විස්තර කර ඇත.[14] 2017 දෙසැම්බර් 8 වන දින බෙනි ප්රදේශයේ සෙමුලිකි හි කැරලිකරුවන්ගේ ප්රහාරයකින් එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සොල්දාදුවන් 14 දෙනෙකු සහ කොංගෝ නිත්ය සොල්දාදුවන් පස් දෙනෙකු මිය ගියහ. කැරලිකරුවන් මිත්ර ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී හමුදාවන් ලෙස සැලකේ.[81] දෙසැම්බර් ප්රහාරයේ එම ආක්රමණිකයා බව එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ විමර්ශනවලින් තහවුරු විය.[82]

2009 දී, නිව් යෝර්ක් ටයිම්ස් වාර්තා කළේ, කොංගෝවේ මිනිසුන් මසකට 45,000ක් ලෙස ඇස්තමේන්තුගත අනුපාතයකින් දිගටම මිය ගිය බවයි[83] - දිගු ගැටුම් වලින් මියගිය සංඛ්යාව 900,000 සිට 5,400,000 දක්වා පරාසයක ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇත.[84] පුලුල්ව පැතිරුනු රෝග සහ සාගතය හේතුවෙන් මරණ සංඛ්යාව සිදුවේ; මිය ගිය පුද්ගලයන්ගෙන් අඩක් පමණ වයස අවුරුදු පහට අඩු දරුවන් බව වාර්තා පෙන්වා දෙයි.[85] ආයුධ රැගෙන යන්නන් සිවිල් වැසියන් ඝාතනය කිරීම, දේපළ විනාශ කිරීම, පුලුල්ව පැතිරුණු ලිංගික හිංසනයන්,[86] ලක්ෂ සංඛ්යාත ජනතාවක් තම නිවෙස්වලින් පලා යාමට හේතු වන අතර, මානුෂීය සහ මානව හිමිකම් නීති උල්ලංඝනය කිරීම් පිළිබඳව නිතර නිතර වාර්තා වී ඇත. එක් අධ්යයනයකින් හෙළි වූයේ කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ සෑම වසරකම කාන්තාවන් 400,000කට වඩා දූෂණයට ලක් වන බවයි.[87] 2018 සහ 2019 දී කොංගෝව ලෝකයේ ඉහළම ලිංගික ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය වාර්තා කර ඇත.[69] හියුමන් රයිට්ස් වොච් සහ නිව් යෝර්ක් විශ්ව විද්යාලය පදනම් කරගත් කොන්ගෝ පර්යේෂණ කණ්ඩායමට අනුව, 2017 ජුනි සිට 2019 ජුනි දක්වා කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි නැගෙනහිර කිවු කලාපයේ සන්නද්ධ හමුදා සිවිල් වැසියන් 1,900 කට අධික සංඛ්යාවක් මරා දමා අවම වශයෙන් පුද්ගලයින් 3,300 ක් පැහැරගෙන ඇත.[88]

කබිලාගේ නිල කාලය සහ බහුවිධ රාජ්ය විරෝධී විරෝධතා

[සංස්කරණය]2015 දී රට පුරා විශාල විරෝධතා ඇති වූ අතර විරෝධතාකරුවන් ඉල්ලා සිටියේ කබිලා ජනාධිපති ධුරයෙන් ඉවත් විය යුතු බවයි. විරෝධතා ආරම්භ වූයේ කොංගෝ ඉහළ මන්ත්රී මණ්ඩලය විසින් ද සම්මත කළහොත් අවම වශයෙන් ජාතික සංගණනයක් පවත්වන තෙක් කබිලාව බලයේ තබා ගත හැකි බවට කොංගෝ පහළ මන්ත්රී මණ්ඩලය විසින් නීතියක් සම්මත කිරීමෙන් පසුවය (මෙම ක්රියාවලිය වසර කිහිපයක් ගතවනු ඇත.) ඔහුට සහභාගී වීම ව්යවස්ථානුකූලව තහනම් කර ඇති සැලසුම් සහගත 2016 මැතිවරණයෙන් පසු ඔහු බලයේ සිටියේය. මෙම පනත සම්මත විය; කෙසේ වෙතත්, සංගණනයක් සිදු වන තෙක් කබිලා බලයේ තබා ගැනීමේ විධිවිධානයෙන් එය ඉවත් කරන ලදී. සංගණනයක් පැවැත්විය යුතු නමුත් එය මැතිවරණ පැවැත්වෙන කාලය සමඟ තවදුරටත් බැඳී නැත. 2015 දී, 2016 අගභාගයේදී මැතිවරණ පැවැත්වීමට නියමිතව තිබූ අතර කොංගෝවේ සාමකාමී වාතාවරණයක් පැවැත්විණි.[89]

2016 නොවැම්බර් 27 වන දින කොංගෝ විදේශ ඇමති රේමන්ඩ් ෂිබන්ඩා මාධ්ය වෙත පැවසුවේ ජනාධිපති කබිලාගේ ධුර කාලය අවසන් වන දෙසැම්බර් 20 න් පසු 2016 දී මැතිවරණයක් නොපවත්වන බවයි. මැඩගස්කරයේ පැවති සම්මන්ත්රණයකදී ෂිබන්ඩා කියා සිටියේ කබිලාගේ රජය කොංගෝවෙන්, එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවිධානයෙන් සහ වෙනත් තැන්වල "මැතිවරණ විශේෂඥයන්ගෙන් උපදෙස් ලබා ගත්" බවත්, "ඡන්දදායකයින් ලියාපදිංචි කිරීමේ මෙහෙයුම 2017 ජූලි 31 දිනෙන් අවසන් කිරීමටත්, 2018 අප්රේල් මාසයේ දී මැතිවරණය පැවැත්වීමටත් තීරණය කර ඇති බවත්ය."[90] කබිලාගේ නිල කාලය අවසන් වූ දෙසැම්බර් 20 වැනිදා රට තුළ විරෝධතා ඇති විය. රට පුරා, විරෝධතාකරුවන් දුසිම් ගනනක් මිය ගිය අතර සිය ගනනක් අත්අඩංගුවට ගන්නා ලදී.

ප්රාදේශීය ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය අලුත් වීම

[සංස්කරණය]වර්තමානයේ නෝර්වීජියානු සරණාගත කවුන්සිලයේ මහලේකම් ජෑන් ඊගෙලන්ඩ් ට අනුව, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි තත්වය 2016 සහ 2017 දී බෙහෙවින් නරක අතට හැරුණු අතර එය බොහෝ අවධානයට ලක්වන සිරියාවේ සහ යේමනයේ යුද්ධ හා සැසඳිය හැකි ප්රධාන සදාචාරාත්මක හා මානුෂීය අභියෝගයකි. කාන්තාවන් සහ ළමයින් ලිංගික අපයෝජනයට ලක් වන අතර "හැකි සෑම ආකාරයකින්ම අපයෝජනයට ලක් වේ". උතුරු කිවු හි ගැටුමට අමතරව, කසායි කලාපයේ ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය වැඩි විය. සන්නද්ධ කණ්ඩායම් කලාපයේ සහ ජාත්යන්තර වශයෙන් ධනවතුන් වෙනුවෙන් රන්, දියමන්ති, තෙල් සහ කොබෝල්ට් ලබා දීම කරගෙන ගියහ. වාර්ගික හා සංස්කෘතික එදිරිවාදිකම් ද, ආගමික චේතනාවන් සහ කල් දැමූ මැතිවරණ සමඟ දේශපාලන අර්බුදය ද විය. ඊගෙලන්ඩ් පවසන්නේ කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි තත්වය "ස්ථාවර ලෙස නරක" බව මිනිසුන් විශ්වාස කරන නමුත් ඇත්ත වශයෙන්ම එය වඩාත් නරක අතට හැරී ඇති බවයි. "අවුරුදු 15 කට පෙර න්යාය පත්රයේ ඉහළින්ම තිබූ කොංගෝවේ විශාල යුද්ධ නැවතත් නරක අතට හැරෙමින් තිබේ".[91] ගැටුම හේතුවෙන් ඇති වූ රෝපණ හා අස්වනු නෙලීමේ බාධා කිරීම් මිලියන දෙකක පමණ ළමුන්ගේ කුසගින්න උත්සන්න කිරීමට ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇත.[92]

හියුමන් රයිට්ස් වොච් 2017 දී ප්රකාශ කළේ කබිලා සිය ධුර කාලය අවසානයේ ධුරයෙන් ඉවත් වීම ප්රතික්ෂේප කිරීම සම්බන්ධයෙන් රට පුරා ඇති වූ විරෝධතා මැඩපැවැත්වීම සඳහා හිටපු මාර්තු 23 ව්යාපාරයේ සටන්කරුවන් බඳවා ගත් බවයි. "M23 සටන්කාමීන් කොංගෝවේ ප්රධාන නගරවල වීදිවල මුර සංචාරයේ යෙදී සිටි අතර, විරෝධතාකරුවන්ට හෝ ජනාධිපතිවරයාට තර්ජනයක් යැයි සැලකෙන වෙනත් අයට වෙඩි තැබීම හෝ අත්අඩංගුවට ගැනීම" සිදු කරන බව ඔවුහු පැවසූහ.[93]

රජයේ හමුදා සහ ප්රබල ප්රාදේශීය යුධ නායකයෙකු වන ජෙනරල් ඩෙල්ටා අතර මැසිසි හි දරුණු සටන් ඇවිලී ඇත. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ මෙහෙයුම එහි විශාලතම හා වඩාත්ම මිල අධික සාම සාධක උත්සාහයයි, නමුත් එය 2017 දී මැසිසි අසල එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ කඳවුරු පහක් වසා දැමුවේ, එක්සත් ජනපදය විසින් වියදම් කපා හැරීමකින් පසුවය.[94]

2018 මැයි 10 වන දින, කොංගෝ නාරිවේද විශේෂඥ වෛද්ය ඩෙනිස් මුක්වේගේට නොබෙල් සාම ත්යාගය පිරිනමන ලද්දේ ලිංගික හිංසනය යුද්ධයේ සහ සන්නද්ධ ගැටුම්වල ආයුධයක් ලෙස භාවිතා කිරීම අවසන් කිරීමට ගත් උත්සාහය වෙනුවෙන් ය.

2018 වාර්ගික ගැටුම

[සංස්කරණය]2018 දෙසැම්බර් 16-17 දිනවල මයි-නොඩොම්බේ පළාතේ යුම්බි හිදී ගෝත්රික ගැටුමක් ඇති විය. මාසික ගෝත්රික රාජකාරි, ඉඩම්, කෙත්වතු සහ ජල සම්පත් සම්බන්ධයෙන් ඇති වූ ගැඹුරු එදිරිවාදිකම්වලදී ගම් හතරක බනුනු මිනිසුන් 900කට ආසන්න පිරිසක් බටෙන්ඩේ ප්රජාවේ සාමාජිකයන් විසින් ඝාතනය කරන ලදී. බනුනු 100 ක් පමණ කොන්ගෝ ගඟේ මොනින්ඩේ දූපතට ද තවත් 16,000 ක් කොංගෝ ජනරජයේ මකොටිම්පොකෝ දිස්ත්රික්කයට ද පලා ගියහ. ලේ වැගිරීමේදී මිලිටරි ආකාරයේ උපක්රම යොදාගත් අතර සමහර ප්රහාරකයින් හමුදා නිල ඇඳුමින් සැරසී සිටියහ. පළාත් පාලන ආයතන සහ ආරක්ෂක අංශවල කොටස් ඔවුන්ට සහයෝගය ලබා දුන් බවට සැක පහළ විය.[95]

2018 මැතිවරණය සහ නව ජනාධිපති (2018–වර්තමානය)

[සංස්කරණය]

2018 දෙසැම්බර් 30 මහ මැතිවරණයක් පැවැත්විණි. 2019 ජනවාරි 10 වන දින මැතිවරණ කොමිසම විසින් විපක්ෂ අපේක්ෂක ෆීලික්ස් ෂිසෙකේඩි ජනාධිපතිවරණ ජයග්රාහකයා ලෙස ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලද අතර,[96] ඔහු ජනවාරි 24 වන දින නිල වශයෙන් ජනාධිපති ලෙස දිවුරුම් දුන්නේය.[97] කෙසේ වෙතත්, ප්රතිඵල වංචා සහගත බවටත්, ෂිසෙකේඩි සහ කබිලා අතර ගනුදෙනුවක් සිදුවී ඇති බවටත් පුලුල්ව පැතිරුනු සැකයක් මතුවිය. කතෝලික සභාව පැවසුවේ නිල ප්රතිඵලය තම මැතිවරණ නිරීක්ෂකයින් රැස් කළ තොරතුරුවලට අනුරූප නොවන බවයි.[98] කිවු හි ඉබෝලා පැතිරීම මෙන්ම දැනට පවතින හමුදා ගැටුම් ද උපුටා දක්වමින් රජය සමහර ප්රදේශවල මාර්තු දක්වා ඡන්දය ප්රමාද කර තිබුණි. මෙම කලාප විපක්ෂ බලකොටු ලෙස හඳුන්වන බැවින් මෙය විවේචනයට ලක් විය.[99][100][101] 2019 අගෝස්තු මාසයේදී, ෆීලික්ස් ෂිසෙකේඩිගේ සමාරම්භකයෙන් මාස හයකට පසු, සභාග රජයක් ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලදී.[102]

කබිලාගේ දේශපාලන සගයන් ප්රධාන අමාත්යාංශ, ව්යවස්ථාදායකය, අධිකරණය සහ ආරක්ෂක සේවාවන්හි පාලනය පවත්වාගෙන ගියේය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, ෂිසෙකේඩි තම බලය ශක්තිමත් කර ගැනීමට සමත් විය. පියවර මාලාවක් තුළ, ඔහු ජාතික සභාවේ සාමාජිකයින් 500 න් 400 කට ආසන්න පිරිසකගේ සහයෝගය ලබා ගනිමින් තවත් නීති සම්පාදකයින් දිනා ගත්තේය. පාර්ලිමෙන්තු දෙකේම කබිලාට පක්ෂපාතී කථිකයන් බලෙන් එළියට දැමීය. 2021 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී කබිලාගේ ආධාරකරුවන් නොමැතිව නව රජය පිහිටුවන ලදී.[103]

රට තුළ විශාල සරම්ප පැතිරීමකින් 2019 දී 5,000 කට ආසන්න පිරිසක් මිය ගියහ.[104] ඉබෝලා වසංගතය 2020 ජුනි මාසයේදී අවසන් වූ අතර එය වසර 2ක් තුළ මරණ 2,280ක් සිදු විය.[105] Équateur පළාතේ තවත් කුඩා ඉබෝලා රෝගයක් 2020 ජුනි මාසයේදී ආරම්භ වූ අතර අවසානයේ මරණ 55 ක් සිදු විය..[106][107] ගෝලීය COVID-19 වසංගතය ද 2020 මාර්තු මාසයේදී කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වෙත ළඟා වූ අතර, එන්නත් කිරීමේ ව්යාපාරයක් 2021 අප්රේල් 19 වන දින ආරම්භ විය.[108][109]

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ඉතාලි තානාපති ලූකා අත්තනාසියෝ සහ ඔහුගේ ආරක්ෂකයා 2021 පෙබරවාරි 22 වන දින උතුරු කිවු හි දී ඝාතනය කරන ලදී.[110] 2021 අප්රේල් 22 වන දින, කෙන්යානු ජනාධිපති උහුරු කෙන්යාටා සහ ෂිසෙකේඩි අතර රැස්වීම්වල ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස දෙරට අතර ජාත්යන්තර වෙළඳාම සහ ආරක්ෂාව (ප්රතිත්රස්තවාදය, ආගමන, සයිබර් ආරක්ෂාව සහ රේගු) වැඩි කිරීමට නව ගිවිසුම් ඇති විය.[111] 2022 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේදී රට තුළ කුමන්ත්රණයක් පිළිබඳ අවිනිශ්චිතතාවයට තුඩු දුන් නමුත්[112] කුමන්ත්රණ උත්සාහය අසාර්ථක විය.[113]

භූගෝලය

[සංස්කරණය]

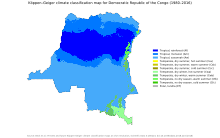

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය පිහිටා ඇත්තේ මධ්යම උප සහරා අප්රිකාවේ, වයඹ දෙසින් කොංගෝ ජනරජය, උතුරින් මධ්යම අප්රිකානු ජනරජය, ඊසාන දෙසින් දකුණු සුඩානය, නැගෙනහිරින් උගන්ඩාව, රුවන්ඩාව සහ බුරුන්ඩි, සහ ටැන්සානියාව (ටැංගනිකා විල හරහා), දකුණින් සහ ගිනිකොන දෙසින් සැම්බියාවෙන්, නිරිත දෙසින් ඇන්ගෝලාවෙන්, සහ බටහිරින් දකුණු අත්ලාන්තික් සාගරයෙන් සහ බටහිරින් ඇන්ගෝලාවේ කැබින්ද පළාතෙන් මායිම්වය. රට පිහිටා ඇත්තේ අක්ෂාංශ 6°N සහ 14°S අතර දේශාංශ 12°E සහ 32°E අතර ය. එය උතුරින් තුනෙන් එකක් සහ දකුණින් තුනෙන් දෙකක් සමඟ සමකය හරහා ගමන් කරයි. වර්ග කිලෝමීටර් 2,345,408 (වර්ග සැතපුම් 905,567) ක භූමි ප්රමාණයකින් යුත් එය ඇල්ජීරියාවට පසුව, ප්රදේශය අනුව අප්රිකාවේ දෙවන විශාලතම රට වේ.

එහි සමක පිහිටීම හේතුවෙන්, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ඉහළ වර්ෂාපතනයක් අත්විඳින අතර ලෝකයේ වැඩිම ගිගුරුම් සහිත වැසි ඇති වේ. සමහර ස්ථානවල වාර්ෂික වර්ෂාපතනය මිලිමීටර 2,000 (අඟල් 80) ඉක්මවිය හැකි අතර, ඇමසන් වනාන්තරයෙන් පසුව ලෝකයේ දෙවන විශාලතම වැසි වනාන්තරය වන කොංගෝ වැසි වනාන්තරය මෙම ප්රදේශය පවත්වා ගෙන යයි. සශ්රීක වනාන්තරයේ මෙම දැවැන්ත ව්යාප්තිය බටහිරින් අත්ලාන්තික් සාගරය දෙසට බෑවුම් වන ගංගාවේ විශාල, පහත් බිම් මධ්යම ද්රෝණියේ වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් ආවරණය කරයි. මෙම ප්රදේශය දකුණින් සහ නිරිත දෙසින් සැවානා වලට ඒකාබද්ධ වන සානු වලින් වටවී ඇති අතර බටහිරින් කඳුකර ටෙරස් සහ උතුරින් කොංගෝ ගඟෙන් ඔබ්බට විහිදෙන තෘණ බිම් වලින් වටවී ඇත. ග්ලැසියර වූ රවෙන්සෝරි කඳු අන්ත නැගෙනහිර කලාපයේ දක්නට ලැබේ.

නිවර්තන දේශගුණය කොංගෝ ගංගා පද්ධතිය ඇති කළ අතර එය ගලා යන වැසි වනාන්තර සමඟ භූගෝලීය වශයෙන් කලාපය ආධිපත්යය දරයි. කොංගෝ ද්රෝණිය මුළු රටම පාහේ අල්ලාගෙන ඇති අතර එය කිලෝමීටර් 1,000,000 (වර්ග සැතපුම් 390,000) ප්රදේශයකි. ගංගාව සහ එහි අතු ගංගා කොංගෝ ආර්ථිකයේ සහ ප්රවාහනයේ කොඳු නාරටිය වේ. ප්රධාන අතු ගංගාවලට කසායි, සංඝා, උබංගි, රුසිසි, අරුවිමි සහ ලුලොංගා ඇතුළත් වේ. කොංගෝ ගඟ ලෝකයේ ඕනෑම ගංගාවක දෙවන විශාලතම ජල ප්රවාහය සහ දෙවන විශාලතම ජල පෝෂකය වේ. (දෙකම ඇමසන් ගඟට පසුපසින්). කොංගෝ ගංගාවේ මූලාශ්ර පිහිටා ඇත්තේ නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු රිෆ්ට් හි බටහිර ශාඛාව මෙන්ම ටැන්ගානිකා විල සහ මුවේරු විල දෙපස පිහිටි ඇල්බර්ටයින් රිෆ්ට් කඳුකරයේ ය. ගංගාව සාමාන්යයෙන් කිසන්ගානි සිට බොයෝමා ඇල්ලට මදක් පහළින් බටහිරට ගලා බසී, පසුව ක්රමයෙන් නිරිත දෙසට නැමී, ම්බණ්ඩකා පසුකර, උබංගි ගඟ හා එක් වී, මැලේබෝ (ස්ටැන්ලි තටාකය) තටාකයට ගලා යයි. කිංෂාසා සහ බ්රසාවිල් තටාකයේ ගඟේ ප්රතිවිරුද්ධ පැතිවල පිහිටා ඇත. එවිට ගංගාව පටු වී ගැඹුරු කැනියන් කිහිපයක් හරහා වැටී, එය සාමූහිකව ලිවිංස්ටෝන් දිය ඇල්ල ලෙස හැඳින්වේ, සහ බෝමා පසුකර අත්ලාන්තික් සාගරයට දිව යයි. ගංගාව සහ එහි උතුරු ඉවුරේ කිලෝමීටර 37ක් පළල (සැතපුම් 23) වෙරළ තීරයක් අත්ලාන්තික් සාගරයට රටෙහි එකම පිටවීම සපයයි.

කොංගෝවේ භූගෝලය හැඩගැස්වීමේදී ඇල්බර්ටයින් රිෆ්ට් ප්රධාන කාර්යභාරයක් ඉටු කරයි. රටේ ඊසානදිග කොටස වඩාත් කඳු සහිත වනවා පමණක් නොව, භූගෝලීය චලනයන් ගිනිකඳු ක්රියාකාරකම් ඇති කරයි, සමහර විට ජීවිත අහිමි වේ. මෙම ප්රදේශයේ භූ විද්යාත්මක ක්රියාකාරකම් හේතුවෙන් අප්රිකානු මහා විල් ද නිර්මාණය විය, ඉන් හතරක් කොංගෝවේ නැගෙනහිර මායිමේ පිහිටා ඇත: ඇල්බට් විල, කිවු විල, එඩ්වඩ් විල සහ ටැන්ගානිකා විල.

රිෆ්ට් නිම්නය කොංගෝවේ දකුණු හා නැගෙනහිර පුරා ඛනිජ සම්පත් විශාල ප්රමාණයක් හෙළිදරව් කර ඇති අතර එය පතල් කැණීමට ප්රවේශ විය හැකිය. කොබෝල්ට්, තඹ, කැඩ්මියම්, කාර්මික සහ මැණික් ගුණාත්මක දියමන්ති, රන්, රිදී, සින්ක්, මැංගනීස්, ටින්, ජර්මනියම්, යුරේනියම්, රේඩියම්, බොක්සයිට්, යකඩ යපස් සහ ගල් අඟුරු, විශේෂයෙන්ම කොංගෝවේ ගිනිකොනදිග කටන්ගා ප්රදේශයේ බහුලව දක්නට ලැබේ.[114]

2002 ජනවාරි 17 වන දින, නයිරගොන්ගෝ කන්ද පුපුරා ගිය අතර, අතිශය තරල ලාවා ධාරා තුනක් පැයට කිලෝමීටර 64 (පැයට සැතපුම් 40) සහ මීටර් 46 (යාර 50) පළලින් ගලා ගියේය. 45 දෙනෙකු මිය ගිය අතර 120,000 කට නිවාස අහිමි වූ අතර, එම ගංගා තුනෙන් එකක් කෙලින්ම ගෝමා හරහා ගලා ගියේය. පුපුරා යාමේදී 400,000 කට අධික පිරිසක් නගරයෙන් ඉවත් කරන ලදී. ලාවා ගලා ගොස් කිවු විලෙහි ජලය විෂ වී එහි ශාක, සතුන් සහ මාළු මරා දැමීය. ගබඩා කර තිබූ පෙට්රල් පුපුරා යාමේ හැකියාව නිසා ගුවන් යානා දෙකක් පමණක් ප්රාදේශීය ගුවන් තොටුපළෙන් පිටත් විය. ලාවා ගුවන් තොටුපළ හරහා ගලා ගොස් ධාවන පථයක් විනාශ කර නවතා තිබූ ගුවන් යානා කිහිපයක් සිර කළේය. සිද්ධියෙන් මාස හයකට පසු, අසල පිහිටි නයමුරගිර කන්ද ද පුපුරා ගියේය. කන්ද පසුව 2006 දී නැවත වරක් පුපුරා ගියේය, නැවත වරක් 2010 ජනවාරි මාසයේදී පිපිරීය.[115]

ජෛව විවිධත්වය සහ සංරක්ෂණය

[සංස්කරණය]

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ වැසි වනාන්තරවල සාමාන්ය චිම්පන්සි සහ බොනෝබෝ (හෝ පිග්මි චිම්පන්සි), අප්රිකානු වනාන්තර අලි, කඳු ගෝරිල්ලා, ඔකාපි, කැලෑ මී හරක්, දිවියා සහ, වැනි දුර්ලභ හා ආවේණික විශේෂ රැසක් ඇතුළුව විශාල ජෛව විවිධත්වයක් ඇත. රටේ තව දුරටත් දකුණට, දකුණු සුදු රයිනෝසිරස්. රටේ ජාතික වනෝද්යාන පහක් ලෝක උරුම අඩවි ලෙස ලැයිස්තුගත කර ඇත: ගරුම්බා, කහුසි-බීගා, සලෝංග සහ විරුංගා යන ජාතික වනෝද්යාන සහ ඔකාපි වනජීවී රක්ෂිතය. කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය මෙගාඩිවර්ස් රටවල් 17 න් එකක් වන අතර එය වඩාත් ජෛව විවිධත්වයෙන් යුත් අප්රිකානු රට වේ.[116]

සංරක්ෂණවාදීන් විශේෂයෙන් ප්රයිමේටස් ගැන කනස්සල්ලට පත්ව ඇත. කොංගෝවේ මහා වානර විශේෂ කිහිපයක් වාසය කරයි: ඒ සාමාන්ය චිම්පන්සියා (Pan troglodytes), බොනොබෝ (Pan paniscus), නැගෙනහිර ගෝරිල්ලා (Gorilla beringei) සහ බටහිර ගෝරිල්ලා (Gorilla gorilla) වේ.[117] බොනොබෝස් වනාන්තරයේ දක්නට ලැබෙන ලොව එකම රට එයයි. මහා වානර වඳවීම ගැන බොහෝ කනස්සල්ල මතු වී ඇත. දඩයම් කිරීම සහ වාසස්ථාන විනාශ කිරීම හේතුවෙන්, චිම්පන්සි, බොනොබෝ සහ ගෝරිල්ලන්ගේ සංඛ්යාව (එක් එක් ජනගහණයක් වරක් මිලියන ගණනක් වූ) දැන් ගෝරිල්ලන් 200,000 ක්, චිම්පන්සියන් 100,000 ක් සහ සමහර විට බොනොබෝස් 10,000 ක් පමණ දක්වා අඩු වී ඇත.[118][119] ගෝරිල්ලන්, චිම්පන්සියන්, බොනොබෝ සහ ඔකාපි යන සතුන් සියල්ලම ලෝක සංරක්ෂණ සංගමය විසින් වඳවීමේ තර්ජනයට ලක්ව ඇත.

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ප්රධාන පාරිසරික ගැටළු අතර වන විනාශය, දඩයම් කිරීම, වනජීවී ජනගහනයට තර්ජනයක් වන, ජල දූෂණය සහ පතල් කැණීම් ඇතුළත් වේ. 2015 සිට 2019 දක්වා කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ වන විනාශය දෙගුණ වී ඇත.[120] 2021 දී, කොංගෝලියානු වැසි වනාන්තරවල වන විනාශය 5% කින් වැඩි විය.[121]

පරිපාලන අංශ

[සංස්කරණය]රට දැනට කිංෂාසා නගර-පළාත සහ අනෙකුත් පළාත් 25 කට බෙදා ඇත. පළාත් 145 කට සහ නගර 32 කට බෙදා ඇත. 2015ට පෙර රටේ පළාත් 11ක් තිබුණා.[122]

රජය සහ දේශපාලනය

[සංස්කරණය]

ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථා දෙකක් අතර වසර හතරක අන්තරයකින් පසු, ආණ්ඩුවේ විවිධ මට්ටම්වල පිහිටුවා ඇති නව දේශපාලන ආයතන මෙන්ම රටපුරා පළාත් සඳහා නව පරිපාලන අංශ ද සමඟින්, 2006 දී නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාවක් ක්රියාත්මක වූ අතර ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ දේශපාලනය කොංගෝව අවසානයේ ස්ථාවර ජනාධිපති ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයක් බවට පත් විය. 2003 සංක්රාන්ති ව්යවස්ථාව[123] මගින් සෙනෙට් සභාවකින් සහ ජාතික සභාවකින් සමන්විත ද්විමණ්ඩල ව්යවස්ථාදායකයක් සහිත පාර්ලිමේන්තුවක් ස්ථාපිත කර තිබුණි.

රටේ නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව සම්පාදනය කිරීමේ වගකීම වෙනත් දේ අතර සෙනෙට් සභාවට තිබුණි. විධායක බලය ජනාධිපතිවරයෙකු සහ උප ජනාධිපතිවරුන් හතර දෙනෙකුගේ ප්රධානත්වයෙන් යුත් 60 දෙනෙකුගෙන් යුත් කැබිනට් මණ්ඩලයකට පැවරී ඇත. ත්රිවිධ හමුදාවේ සේනාධිනායකයා වූයේද ජනාධිපතිවරයාය. සංක්රාන්ති ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව මගින් ව්යවස්ථාමය අර්ථකථන බලතල සහිත ශ්රේෂ්ඨාධිකරණය ප්රධානත්වයෙන් සාපේක්ෂ ස්වාධීන අධිකරණයක් ද පිහිටුවන ලදී.[124]

තුන්වන ජනරජයේ ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව ලෙසද හැඳින්වෙන 2006 ව්යවස්ථාව 2006 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේ සිට ක්රියාත්මක විය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, 2006 ජූලි මැතිවරණයෙන් මතු වූ තේරී පත් වූ නිලධාරීන්ගේ පදවි ප්රාප්තිය දක්වා සංක්රාන්ති ව්යවස්ථාව සමඟ එයට සමගාමී අධිකාරියක් තිබුණි. නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව යටතේ ව්යවස්ථාදායකය ද්විමණ්ඩල ලෙස පැවතුනි; විධායකය සමගාමීව ජනාධිපතිවරයෙකු විසින් භාර ගන්නා ලද අතර අගමැතිවරයෙකුගේ නායකත්වයෙන් යුත් රජය, ජාතික සභාවේ බහුතරයක් ලබා ගත හැකි පක්ෂයෙන් පත් කරන ලදී.

රජය - ජනාධිපතිවරයා නොවේ - පාර්ලිමේන්තුවට වගකිව යුතුය. නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව මඟින් පළාත් ආණ්ඩුවලට නව බලතල ද ලබා දී ඇති අතර, ඔවුන් තෝරා පත් කර ගන්නා ආණ්ඩුකාරවරයා සහ පළාත් ආණ්ඩුවේ ප්රධානියා අධීක්ෂණය කරන පළාත් පාර්ලිමේන්තු නිර්මාණය කළේය. අලූත් ආයතන තුනකට බෙදුණු ශ්රේෂ්ඨාධිකරණය අතුරුදන් වීම නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාවෙන් ද දක්නට ලැබිණි. ශ්රේෂ්ඨාධිකරණයේ ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාමය අර්ථ නිරූපණ වරප්රසාදය දැන් ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථා අධිකරණය සතුය.[125]

මධ්යම අප්රිකා එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ උප කලාපයේ පිහිටා තිබුණද, ජාතිය දකුණු අප්රිකානු සංවර්ධන ප්රජාවේ (SADC) සාමාජිකයෙකු ලෙස දකුණු අප්රිකාව සමඟ ආර්ථික වශයෙන් සහ කලාපීය වශයෙන් අනුබද්ධ වේ.[126]

විදේශ සබඳතා

[සංස්කරණය]

හිඟ අමුද්රව්ය සඳහා ඉල්ලුමේ ගෝලීය වර්ධනය සහ චීනය, ඉන්දියාව, රුසියාව, බ්රසීලය සහ අනෙකුත් සංවර්ධනය වෙමින් පවතින රටවල කාර්මික නැගීම් හේතුවෙන් සංවර්ධිත රටවල් නව සම්පත් හඳුනා ගැනීම් සහ සහතික කිරීම සඳහා උපාය මාර්ග ලෙස අඛණ්ඩ පදනමක් මත රටේ ආරක්ෂක අවශ්යතා සඳහා අවශ්ය උපායමාර්ගික සහ තීරණාත්මක ද්රව්ය ප්රමාණවත් සැපයුමක් ලබා දේ.[127] එක්සත් ජනපදයේ ජාතික ආරක්ෂාව සඳහා කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි වැදගත්කම ඉස්මතු කරමින්, ප්රභූ කොංගෝ ඒකකයක් පිහිටුවීමේ ප්රයත්නය මෙම මූලෝපායික වශයෙන් වැදගත් කලාපය තුළ සන්නද්ධ හමුදා වෘත්තීමය කිරීම සඳහා එක්සත් ජනපදයේ නවතම උත්සාහයයි.[128]

බොහෝ කාර්මික සහ මිලිටරි යෙදුම් සඳහා භාවිතා කරන උපායමාර්ගික සහ තීරණාත්මක ලෝහයක් වන කොබෝල්ට් වැනි ස්වාභාවික සම්පත් වලින් පොහොසත් කොංගෝවට වැඩි ආරක්ෂාවක් ගෙන ඒම සඳහා ආර්ථික සහ උපාය මාර්ගික දිරිගැන්වීම් තිබේ.[127] කොබෝල්ට් විශාලතම භාවිතය වන්නේ ජෙට් එන්ජින් කොටස් සෑදීමට භාවිතා කරන සුපිරි මිශ්ර ලෝහ වලය. කොබෝල්ට් චුම්බක මිශ්ර ලෝහවල සහ සිමෙන්ති කාබයිඩ් වැනි කැපීමේ සහ ඇඳුම්-ප්රතිරෝධී ද්රව්යවල ද භාවිතා වේ. ඛනිජ තෙල් සහ රසායනික සැකසුම් සඳහා උත්ප්රේරක ඇතුළු විවිධ යෙදුම්වල රසායනික කර්මාන්තය සැලකිය යුතු ප්රමාණයකින් කොබෝල්ට් පරිභෝජනය කරයි; තීන්ත සහ තීන්ත සඳහා වියළන කාරක; පෝසිලේන් එනමල් සඳහා බිම් කබා; පිඟන් මැටි සහ වීදුරු සඳහා වර්ණක; සහ සෙරමික්, තීන්ත සහ ප්ලාස්ටික් සඳහා වර්ණක සදහා භාවිතා වේ. ලෝකයේ කොබෝල්ට් සංචිතවලින් 80% ක් රට සතුය.[129]

විද්යුත් වාහන සඳහා බැටරි සඳහා කෝබෝල්ට් වල වැදගත්කම සහ විදුලි මිශ්රණයේ කඩින් කඩ පුනර්ජනනීය ද්රව්ය විශාල ප්රමාණයක් සහිත විද්යුත් ජාල ස්ථායීකරණය හේතුවෙන්, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වැඩි භූ දේශපාලන තරඟයක වස්තුවක් බවට පත්විය හැකි යැයි සිතේ.[127]

21 වන ශතවර්ෂයේ දී, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි චීන ආයෝජන සහ චීනය වෙත කොංගෝ අපනයනය වේගයෙන් වර්ධනය වී ඇත. 2019 ජූලි මාසයේදී, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ඇතුළු රටවල් 37 ක එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ තානාපතිවරු, උයිගුර්වරුන්ට සහ අනෙකුත් මුස්ලිම් වාර්ගික සුළු ජාතීන්ට චීනය සැලකීම ආරක්ෂා කරමින් එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ මානව හිමිකම් කවුන්සිලයට ඒකාබද්ධ ලිපියක් අත්සන් කර ඇත.[130]

2021 දී, ජනාධිපති ෆීලික්ස් ෂිසෙකේඩි, ඔහුගේ පූර්වගාමියා වූ ජෝසෆ් කබිලා විසින්[131] චීනය සමඟ අත්සන් කරන ලද පතල් කොන්ත්රාත්තු සමාලෝචනය කරන ලෙස ඉල්ලා සිටියේය, විශේෂයෙන් බිලියන ගණනක සිකොමයින් 'යටිතල පහසුකම් සඳහා ඛනිජ' ගනුදෙනුව ප්රධාන වේ.[132]

හමුදා ශක්තිය

[සංස්කරණය]

Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC) පුද්ගලයන් 144,000කින් පමණ සමන්විත වන අතර ඔවුන්ගෙන් බහුතරයක් ගොඩබිම් හමුදාවේ කොටසක් වන අතර කුඩා ගුවන් හමුදාවක් සහ ඊටත් වඩා කුඩා නාවික හමුදාවක් ද වේ. දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධය අවසන් වීමෙන් පසු 2003 දී FARDC පිහිටුවන ලද අතර බොහෝ හිටපු කැරලිකාර කණ්ඩායම් එහි ශ්රේණිවලට ඒකාබද්ධ කරන ලදී. නොහික්මුණු සහ දුර්වල පුහුණුව ලත් හිටපු කැරලිකරුවන් සිටීම මෙන්ම අරමුදල් නොමැතිකම සහ විවිධ මිලීෂියාවන්ට එරෙහිව වසර ගණනාවක් සටන් කිරීම හේතුවෙන්, FARDC අධික දූෂණයෙන් හා අකාර්යක්ෂමතාවයෙන් පීඩා විඳිති. දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධය අවසානයේ අත්සන් කරන ලද ගිවිසුම්, කබිලාගේ රජයේ හමුදා (FAC), RCD සහ MLC වලින් සමන්විත නව "ජාතික, ප්රතිව්යුහගත සහ ඒකාබද්ධ" හමුදාවක් ඉල්ලා සිටියේය. RCD-N, RCD-ML සහ Mai-Mai වැනි කැරලිකරුවන් නව සන්නද්ධ හමුදාවන්හි කොටසක් බවට පත්වන බව ද නියම කර ඇත. වටලෑමේ හෝ යුද්ධයේ ප්රාන්ත ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන සහ ආරක්ෂක අංශ ප්රතිසංස්කරණ, නිරායුධකරණය / බලමුලු ගැන්වීම සහ ජාතික ආරක්ෂක ප්රතිපත්ති පිළිබඳ උපදෙස් ලබා දෙන සුපිරි ආරක්ෂක කවුන්සිලයක් නිර්මාණය කිරීම සඳහා ද එය සපයන ලදී. FARDC සංවිධානය කරනු ලබන්නේ කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ පළාත් පුරා විසිරී ඇති සේනාංක පදනම් කරගෙන ය. කොංගෝ හමුදා නැගෙනහිර උතුරු කිවු කලාපයේ කිවු ගැටුමට, ඉටුරි කලාපයේ ඉටුරි ගැටුමට සහ දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධයේ සිට අනෙකුත් කැරලිවලට එරෙහිව සටන් කරමින් සිටිති. FARDC හැරුණු විට, එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ විශාලතම සාම සාධක මෙහෙයුම වන MONUSCO ලෙස හඳුන්වනු ලබන අතර, සාම සාධක භටයින් 18,000ක් පමණ රට තුළ පවතී.

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය න්යෂ්ටික අවි තහනම් කිරීම පිළිබඳ එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ ගිවිසුමට අත්සන් තැබීය.[133]

දූෂණය

[සංස්කරණය]මොබුටුගේ ඥාතියෙක් ඔහුගේ පාලන කාලය තුළ රජය අයථා ලෙස ආදායම් එකතු කළ ආකාරය පැහැදිලි කළේය: "මොබුටු අපේ එකාට බැංකුවට ගිහින් මිලියනයක් ගන්න කියනවා. අපි අතරමැදියෙක් ළඟට ගිහින් එයාට කියනවා මිලියන පහක් ගන්න කියලා. ඔහු මොබුටුගේ බලය ඇතිව බැංකුවට ගොස් දහය එළියට ගත්තා. මොබුටුට එකක් ලැබුණා, අපි අනෙක් නවය ගත්තා."[134] 1996 දී ආර්ථික බිඳවැටීමකට තුඩු දුන් දේශපාලන ප්රතිවාදීන් ඔහුගේ පාලනයට අභියෝග කිරීම වැළැක්වීම සඳහා මොබුටු දූෂණය ආයතනගත කළේය.[135]

මොබුටු බලයේ සිටියදී ඇමෙරිකානු ඩොලර් බිලියන 4-5ක් සොරකම් කළ බවට චෝදනා එල්ල විය.[136] ඔහු කිසිම ආකාරයකින් පළමු දූෂිත කොංගෝ නායකයා නොවීය: "සංවිධානාත්මක සොරකම් කිරීමේ පද්ධතියක් ලෙස ආන්ඩුව II ලියෝපෝල්ඩ් රජු වෙත ආපසු යයි", 2009 දී ඇඩම් හොච්ස්චයිල්ඩ් සඳහන් කළේය.[137] 2009 ජූලි මාසයේදී ස්විට්සර්ලන්ත අධිකරණයක් තීරණය කළේ ජාත්යන්තර වත්කම් ප්රතිසාධන නඩුවක සීමාවන් ප්රඥප්තිය අවසන් වී ඇති බවත්, මොබුටුගේ ස්විස් බැංකුවක තැන්පත් කර ඇති ඩොලර් මිලියන 6.7 ක පමණ වත්කම් මොබුටුගේ පවුලට ආපසු ලබා දිය යුතු බවත් ය.[138]

ජනාධිපති කබිලා 2001 දී බලයට පත්වීමෙන් පසු ආර්ථික අපරාධ මර්දන කොමිසම පිහිටුවන ලදී.[139] කෙසේ වෙතත්, 2016 දී Enough ව්යාපෘතිය කොංගෝව ප්රචණ්ඩකාරී ක්ලෙප්ටොක්රැසියක් ලෙස පවත්වාගෙන යන බවට වාර්තාවක් නිකුත් කළේය.[140]

2020 ජූනි මාසයේදී, කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ අධිකරණයක් විසින් ජනාධිපති ෂිසෙකේඩිගේ මාණ්ඩලික ප්රධානී Vital Kamerhe දූෂණයට වරදකරු බව තීරණය කළේය. ඩොලර් මිලියන 50ක් (පවුම් මිලියන 39ක්) පමණ රාජ්ය මුදල් අවභාවිත කිරීමේ චෝදනාවට මුහුණ දීමෙන් පසුව ඔහුට වසර 20ක බරපතළ වැඩ සහිත සිර දඬුවමක් නියම විය. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි දූෂණ සම්බන්ධයෙන් වරදකරු වූ ඉහළම පුද්ගලයා ඔහු විය.[141] කෙසේ වෙතත්, Kamerhe දැනටමත් 2021 දෙසැම්බර් මාසයේදී නිදහස් කරන ලදී.[142]

2021 නොවැම්බරයේදී, කබිලා සහ ඔහුගේ සගයන් ඉලක්ක කර ගනිමින් කිංෂාසා හි අධිකරණ පරීක්ෂණයක් ආරම්භ කරන ලද්දේ ඩොලර් මිලියන 138 ක වංචාවක් සිදු කළ බවට හෙළිදරව් වීමෙන් පසුවය.[143]

මානව හිමිකම්

[සංස්කරණය]

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ ජාත්යන්තර අපරාධ අධිකරණ විමර්ශනය 2004 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී කබිලා විසින් ආරම්භ කරන ලදී. ජාත්යන්තර අපරාධ අධිකරණයේ අභිචෝදකයා 2004 ජූනි මාසයේදී නඩුව ආරම්භ කළේය. ළමා සොල්දාදුවන්හි කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය විශාල පරිමාණයෙන් භාවිතා කර ඇති අතර 2011 දී එය ඇස්තමේන්තු කරන ලදී. ළමයින් 30,000ක් තවමත් සන්නද්ධ කණ්ඩායම් සමඟ ක්රියාත්මක වේ.[144] 2013 දී කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ළමා ශ්රමයේ නරකම ආකාරයන් පිළිබඳ එක්සත් ජනපද කම්කරු දෙපාර්තමේන්තුවේ සොයාගැනීම් අනුව ළමා ශ්රමය සහ බලහත්කාර ශ්රමය පිළිබඳ අවස්ථා නිරීක්ෂණය කර වාර්තා කර ඇති අතර[145] ළමා ශ්රමය හෝ බලහත්කාර ශ්රමය මගින් රටේ පතල් කර්මාන්තය විසින් නිෂ්පාදනය කරන ලද භාණ්ඩ හයක් දෙපාර්තමේන්තුවේ 2014 දෙසැම්බර් නිෂ්පාදනය කරන ලද භාණ්ඩ ලැයිස්තුවේ දැක්වේ.

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය 2006 වසරේ සිට සමලිංගික විවාහ තහනම් කර ඇති අතර,[146] LGBT ප්රජාව කෙරෙහි දක්වන ආකල්ප සාමාන්යයෙන් ජාතිය පුරා ඍණාත්මක වේ.[147]

අපරාධ සහ නීතිය ක්රීයාත්මක කිරීම

[සංස්කරණය]කොංගෝ ජාතික පොලිසිය යනු කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ මූලික පොලිස් බලකායයි.[148]

කාන්තාවන්ට එරෙහි හිංසනය

[සංස්කරණය]කාන්තාවන්ට එරෙහි හිංසනය සාමාන්ය දෙයක් ලෙස සමාජයේ විශාල අංශ විසින් වටහාගෙන ඇති බව පෙනේ.[149] 2013-2014 DHS සමීක්ෂණය (පිටු. 299) සොයාගෙන ඇත්තේ, යම් යම් තත්වයන් යටතේ ස්වාමිපුරුෂයෙකු තම බිරිඳට පහර දීම යුක්ති සහගත බව කාන්තාවන්ගෙන් 74.8% ක් එකඟ වූ බවයි.[150]

2006 දී එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ කාන්තාවන්ට එරෙහි වෙනස්කම් ඉවත් කිරීම පිළිබඳ කමිටුව පශ්චාත් යුධ සංක්රාන්ති සමය තුළ කාන්තාවන්ගේ මානව හිමිකම් සහ ස්ත්රී පුරුෂ සමානාත්මතාවය ප්රවර්ධනය කිරීම ප්රමුඛතාවයක් ලෙස නොසැලකීම ගැන කනස්සල්ල පළ කළේය.[151][152] කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ සන්නද්ධ හමුදා සහ රටේ නැගෙනහිර ප්රදේශයේ සන්නද්ධ කණ්ඩායම් විසින් සමූහ දූෂණ, ලිංගික ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය සහ ලිංගික වහල්භාවය යුද අවියක් ලෙස භාවිතා කරයි.[153] විශේෂයෙන්ම රටේ නැඟෙනහිර ප්රදේශය "ලෝකයේ ස්ත්රී දූෂණ අගනුවර" ලෙස විස්තර කර ඇති අතර එහි පැතිරී ඇති ලිංගික ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය ලෝකයේ නරකම ලෙස විස්තර කර ඇත.[154][155]

කාන්තා ලිංගික ඡේදනය (FGM) මහා පරිමාණයෙන් සිදු නොවූවත් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ද සිදු කෙරේ. FGM පැතිරීම කාන්තාවන්ගෙන් 5% ක් ලෙස ගණන් බලා ඇත.[156][157] FGM නීති විරෝධී ය: ලිංගික ඉන්ද්රියන්ගේ "ශාරීරික හෝ ක්රියාකාරී අඛණ්ඩතාව" උල්ලංඝනය කරන ඕනෑම පුද්ගලයෙකුට නීතියෙන් වසර දෙකේ සිට පහ දක්වා සිර දඬුවමක් සහ කොංගෝ ෆ්රෑන්ක් 200,000 ක දඩයක් නියම කෙරේ.[158][159]

2007 ජූලි මාසයේදී ජාත්යන්තර රතු කුරුස කමිටුව නැගෙනහිර කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි තත්වය ගැන කනස්සල්ල පළ කළේය.[160] "පෙන්ඩුලම් විස්ථාපනය" සංසිද්ධියක් වර්ධනය වී ඇති අතර, මිනිසුන් රාත්රියේදී ආරක්ෂිත ස්ථානයට ඉක්මන් වේ. 2007 ජූලි මාසයේදී නැගෙනහිර කොංගෝවේ සංචාරය කළ කාන්තාවන්ට එරෙහි ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය පිළිබඳ එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ විශේෂ වාර්තාකරු යකින් එර්ටර්ක් ට අනුව, උතුරු සහ දකුණු කිවු හි කාන්තාවන්ට එරෙහි ප්රචණ්ඩත්වයට "හිතාගත නොහැකි ම්ලේච්ඡත්වය" ඇතුළත් විය. "සන්නද්ධ කණ්ඩායම් ප්රාදේශීය ප්රජාවන්ට පහර දීම, කොල්ලකෑම, දූෂණය කිරීම, කාන්තාවන් සහ ළමයින් පැහැරගෙන යාම සහ ඔවුන් ලිංගික වහලුන් ලෙස වැඩ කිරීමට සලස්වන" බව එර්ටර්ක් තවදුරටත් පැවසීය.[161] 2008 දෙසැම්බරයේදී, ගාඩියන් හි ගාඩියන් ෆිල්ම්ස් විසින් කොල්ලකෑම් මිලීෂියා විසින් අපයෝජනයට ලක් වූ 400 කට අධික කාන්තාවන් සහ ගැහැණු ළමයින්ගේ සාක්ෂි ලේඛනගත කරන චිත්රපටයක් නිකුත් කරන ලදී.[162]

2010 ජුනි මාසයේදී ඔක්ස්ෆෑම් කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ ස්ත්රී දූෂණ සංඛ්යාවේ නාටකාකාර වර්ධනයක් වාර්තා කළ අතර හාවඩ් හි පර්යේෂකයන් සොයා ගත්තේ සිවිල් වැසියන් විසින් සිදු කරන ලද දූෂණ දහහත් ගුණයකින් වැඩි වී ඇති බවයි.[163] 2014 ජූනි මාසයේදී ෆ්රීඩම් ෆ්රම් ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලද්දේ දේශපාලනිකව ක්රියාකාරී කාන්තාවන්ට දඬුවම් වශයෙන් කොංගෝ බන්ධනාගාරවල රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන් විසින් සාමාන්ය ලෙස ස්ත්රී දූෂණ සහ ලිංගික හිංසනය භාවිතා කරන බවට වාර්තා වී ඇති බවයි.[164] වාර්තාවේ ඇතුළත් කාන්තාවන් කින්ෂාසා අගනුවර ඇතුළු රට පුරා ස්ථාන කිහිපයකදී සහ ගැටුම් කලාපවලින් බැහැර වෙනත් ප්රදේශවල අපයෝජනයට ලක්ව ඇත.[164]

2015 දී, ෆිලිම්බි සහ එමානුවෙල් වෙයි වැනි රට තුළ සහ ඉන් පිටත සිටින පුද්ගලයින් 2016 මැතිවරණය ළං වන විට ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය සහ අස්ථාවරත්වය මැඩපැවැත්වීමේ අවශ්යතාවය ගැන කතා කළහ.[165][166]

ආර්ථිකය

[සංස්කරණය]

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ ප්රාථමික මුදල් වර්ගය ලෙස ක්රියා කරන කොංගෝ ෆ්රෑන්ක් සංවර්ධනය සහ නඩත්තු කිරීමේ වගකීම කොංගෝ මහ බැංකුව සතු වේ. 2007 දී, ලෝක බැංකුව කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයට ඉදිරි වසර තුන තුළ ඩොලර් බිලියන 1.3 දක්වා ආධාර අරමුදල් ප්රදානය කිරීමට තීරණය කළේය.[167] කොංගෝ රජය 2009 දී අප්රිකාවේ ව්යාපාර නීතිය සමගි කිරීමේ සංවිධානයේ (OHADA) සාමාජිකත්වය පිළිබඳ සාකච්ඡා ආරම්භ කළේය.[168]

DRC ලෝකයේ ස්වභාවික සම්පත් අතින් පොහොසත්ම රටවලින් එකක් ලෙස පුළුල් ලෙස සැලකේ; එහි ප්රයෝජනයට නොගත් අමු ඛනිජ නිධි වටිනාකම ඇමෙරිකානු ඩොලර් ට්රිලියන 24 ඉක්මවන බව ගණන් බලා ඇත.[169][170][171] කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතුව ලෝකයේ කෝල්ටන්වලින් 70%ක්, කොබෝල්ට්වලින් 33%, දියමන්ති සංචිතවලින් 30%කට වඩා සහ තඹවලින් 10% ක් ඇත.[172][173]

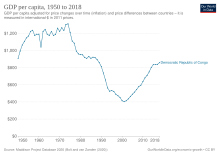

මෙතරම් විශාල ඛනිජ සම්පත් තිබියදීත්, කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ ආර්ථිකය 1980 ගණන්වල මැද භාගයේ සිට විශාල ලෙස පහත වැටී ඇත. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සිය අපනයන ආදායමෙන් 70%ක් දක්වා 1970 ගනන් සහ 1980 ගනන්වල ඛනිජ වලින් උපයා ගත් අතර එම අවස්ථාවේ දී සම්පත් මිල පිරිහුණු විට එය විශේෂයෙන් බලපෑවේය. 2005 වන විට, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ආදායමෙන් 90% ක් එහි ඛනිජ වලින් ලබා ගන්නා ලදී.[174] කොංගෝ පුරවැසියන් පෘථිවියේ දුප්පත්ම ජනතාව අතර වේ. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ලෝකයේ ඒක පුද්ගල දළ දේශීය නිෂ්පාදිතයේ අඩුම හෝ ආසන්නතම නාමික දළ දේශීය නිෂ්පාදිතය අඛණ්ඩව ඇත. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය යනු දූෂණ සංජානන දර්ශකයේ පහළම ශ්රේණිගත රටවල් විස්සෙන් එකකි.

පතල් කැණීම

[සංස්කරණය]

DRC යනු ලොව විශාලතම කොබෝල්ට් ලෝපස් නිෂ්පාදකයා වන අතර තඹ සහ දියමන්ති ප්රධාන නිෂ්පාදකයෙකි.[175] දෙවැන්න බටහිරින් කසායි පළාතෙන් පැමිණේ. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි විශාලතම පතල් දකුණු කටන්ගා පළාතේ පිහිටා ඇති අතර ඒවා ඉතා යාන්ත්රිකකරණය කර ඇති අතර වසරකට තඹ සහ කොබෝල්ට් ලෝපස් ටොන් මිලියන ගණනක ධාරිතාවක් සහ ලෝහ ලෝපස් සඳහා පිරිපහදු කිරීමේ හැකියාව ඇත. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය යනු ලොව දෙවන විශාලතම දියමන්ති නිපදවන ජාතිය වන අතර,[b] එහි නිෂ්පාදනයෙන් වැඩි කොටසක් සඳහා අත්කම් සහ කුඩා පරිමාණ පතල් කම්කරුවන් වගකිව යුතුය.

1960 දී නිදහස ලබන විට, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය දකුණු අප්රිකාවට පසුව අප්රිකාවේ දෙවන වඩාත්ම කාර්මික රට විය; එය සමෘද්ධිමත් පතල් අංශයක් සහ සාපේක්ෂව ඵලදායී කෘෂිකාර්මික අංශයක් ගැන පුරසාරම් දොඩයි.[176] දිගුකාලීන ගැටුම්වල ප්රතිඵලය පිළිබඳ අවිනිශ්චිතතාව, යටිතල පහසුකම් නොමැතිකම සහ දුෂ්කර මෙහෙයුම් පරිසරය හේතුවෙන් විදේශීය ව්යාපාර මෙහෙයුම් සීමා කර ඇත. අවිනිශ්චිත නෛතික රාමුවක්, දූෂණය, උද්ධමනය සහ රජයේ ආර්ථික ප්රතිපත්ති සහ මූල්ය මෙහෙයුම්වල විවෘතභාවය නොමැතිකම වැනි මූලික ගැටලුවල බලපෑම යුද්ධ විසින් තීව්ර කළේය.

2002 අගභාගයේදී, ආක්රමණික විදේශීය හමුදාවන්ගෙන් විශාල කොටසක් ඉවත් වූ විට තත්ත්වය වැඩිදියුණු විය. ජාත්යන්තර මූල්ය අරමුදල සහ ලෝක බැංකු දූත මණ්ඩල ගණනාවක් රජය සමඟ සුසංයෝගී ආර්ථික සැලැස්මක් සකස් කිරීමට උදව් කළ අතර ජනාධිපති කබිලා ප්රතිසංස්කරණ ක්රියාත්මක කිරීමට පටන් ගත්තේය. බොහෝ ආර්ථික ක්රියාකාරකම් තවමත් දළ දේශීය නිෂ්පාදිතයේ දත්තවලට පිටින් පවතී. 2011 වන විට ශ්රේණිගත කළ රටවල් 187 න් අඩුම මානව සංවර්ධන දර්ශකය කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතු විය.[177]

DRC හි ආර්ථිකය පතල් කැණීම මත දැඩි ලෙස රඳා පවතී. කෙසේ වෙතත්, ශිල්පීය පතල් කැණීමේ කුඩා පරිමාණ ආර්ථික ක්රියාකාරකම් අවිධිමත් අංශයේ සිදු වන අතර එය දළ දේශීය නිෂ්පාදිතයේ දත්ත වලින් පිළිබිඹු නොවේ.[178] කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි දියමන්තිවලින් තුනෙන් එකක් හොර රහසේ රටින් පිටට ගෙන යන බව විශ්වාස කෙරෙන අතර, දියමන්ති නිෂ්පාදන මට්ටම් ප්රමාණනය කිරීමට අපහසු වේ.[179] 2002 දී රටේ නැඟෙනහිර ප්රදේශයෙන් ටින් සොයා ගත් නමුත් අද වන විට කැණීම් කර ඇත්තේ කුඩා පරිමාණයෙන් පමණි.[180] කෝල්ටන්, කැසිටරයිට්, ටැන්ටලම් සහ ටින් ලෝපස් වැනි ඛනිජ වර්ග නැගෙනහිර කොංගෝවේ යුද්ධයට උත්තේජක සැපයීය.[181]

ලොව විශාලතම කොබෝල්ට් පිරිපහදුව බවට පත් කරමින් වසරකට තඹ ටොන් 175,000 ක් සහ කොබෝල්ට් ටොන් 8,000 ක ධාරිතාවයකින් යුත් ලුයිලු ලෝහමය කම්හල ස්විට්සර්ලන්තයට අයත් සමාගමක් වන කටන්ගා මයිනින් ලිමිටඩ් සතු වේ. ප්රධාන පුනරුත්ථාපන වැඩසටහනකින් පසු, සමාගම 2007 දෙසැම්බර් මාසයේදී තඹ නිෂ්පාදන මෙහෙයුම් සහ 2008 මැයි මාසයේදී කොබෝල්ට් නිෂ්පාදනය නැවත ආරම්භ කළේය.[182]

2013 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී, දූෂණ විරෝධී රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන හෙළිදරව් කළේ, උත්සන්න වූ නිෂ්පාදනය සහ ධනාත්මක කාර්මික කාර්ය සාධනය තිබියදීත්, පතල් අංශයෙන් ඩොලර් මිලියන 88 ක් ලබා ගැනීමට කොංගෝ බදු බලධාරීන් අපොහොසත් වී ඇති බවයි. අතුරුදහන් වූ අරමුදල් 2010 සිට වන අතර බදු ආයතන ඒවා මහ බැංකුවට ගෙවා තිබිය යුතුය.[183] පසුව 2013 දී, Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative විසින් ප්රමාණවත් වාර්තාකරණය, අධීක්ෂණය සහ ස්වාධීන විගණන හේතුවෙන් සාමාජිකත්වය සඳහා රටේ අපේක්ෂකත්වය අත්හිටුවන ලදී, නමුත් 2013 ජූලි මාසයේදී EITI විසින් රටට පූර්ණ සාමාජිකත්වය ලබා දෙන මට්ටමට රට සිය ගිණුම්කරණ සහ විනිවිදභාවයේ භාවිතයන් වැඩිදියුණු කරන ලදී.

2018 පෙබරවාරියේදී, ගෝලීය වත්කම් කළමනාකරණ සමාගමක් වන AllianceBernstein,[184] විද්යුත් වාහන ධාවනය කරන ලිතියම්-අයන බැටරි සඳහා අත්යවශ්ය වන කොබෝල්ට් සම්පත් නිසා කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ආර්ථික වශයෙන් "විදුලි වාහන යුගයේ සෞදි අරාබිය" ලෙස අර්ථ දැක්වීය.[185]

ගමනාගමනය

[සංස්කරණය]

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ ගොඩබිම් ප්රවාහනය සැමවිටම දුෂ්කර වී ඇත. කොංගෝ ද්රෝණියේ භූමිය සහ දේශගුණය මාර්ග සහ දුම්රිය ඉදිකිරීම් සඳහා බරපතල බාධක ඉදිරිපත් කරන අතර, මෙම විශාල රට හරහා ඇති දුර විශාලය. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතුව යාත්රා කළ හැකි ගංගා ඇති අතර අප්රිකාවේ වෙනත් ඕනෑම රටකට වඩා බෝට්ටුවෙන් සහ තොටුපළෙන් වැඩි මගීන් සහ භාණ්ඩ ප්රවාහනය කරයි, නමුත් රට තුළ, විශේෂයෙන් ග්රාමීය ප්රදේශවල බොහෝ ස්ථාන අතර භාණ්ඩ හා මිනිසුන් ගෙනයාමේ එකම ඵලදායී මාධ්යය ගුවන් ප්රවාහනයයි. නිදන්ගත ආර්ථික වැරදි කළමනාකරණය, දේශපාලන දූෂණය සහ අභ්යන්තර ගැටුම් යටිතල පහසුකම් සඳහා දිගුකාලීන අඩු ආයෝජනයකට තුඩු දී ඇත.

දුම්රිය

[සංස්කරණය]

දුම්රිය ප්රවාහනය සපයනු ලබන්නේ කොංගෝ රේල් රෝඩ්ස් කම්පැනි (Société nationale des chemins de fer du Congo), ඔෆිස් නැෂනල් ඩෙස් ට්රාන්ස්පෝර්ට්ස් කොංගෝ සහ යූලේ රේල්වේයිස් (Office des Chemins de fer des Ueles, CFU). කොංගෝවේ බොහෝ යටිතල පහසුකම් මෙන්ම, දුම්රිය මාර්ග දුර්වල නඩත්තු, අපිරිසිදු, ජනාකීර්ණ සහ අනතුරුදායක වේ.

මහා මාර්ග

[සංස්කරණය]කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතුව එහි ජනගහනයෙන් සහ අප්රිකාවේ ප්රමාණයෙන් ඕනෑම රටකට වඩා අඩු සර්ව කාලගුණයක් සහිත අධිවේගී මාර්ග ඇත — මුළු කිලෝමීටර 2,250 (සැතපුම් 1,400), එයින් හොඳ තත්ත්වයේ ඇත්තේ කිලෝමීටර් 1,226 (සැතපුම් 762) පමණි. මෙය ඉදිරිදර්ශනයක තැබීමට, ඕනෑම දිශාවකට රට හරහා ඇති මාර්ග දුර කිලෝමීටර් 2,500 (සැතපුම් 1,600) (උදා: මතඩි සිට ලුබුම්බාෂි දක්වා, මාර්ගයෙන් කිලෝමීටර් 2,700 (සැතපුම් 1,700)) වේ. කිලෝමීටර් 2,250 (සැතපුම් 1,400) සංඛ්යාව ජනගහනයෙන් මිලියනයකට 35 කිලෝමීටර් (සැතපුම් 22) ක පදික මාර්ගයක් බවට පරිවර්තනය වේ. සැම්බියාව සහ බොට්ස්වානා සඳහා සංසන්දනාත්මක සංඛ්යා පිළිවෙලින් 721 km (448 සැතපුම්) සහ 3,427 km (2,129 mi) වේ.[c]

ට්රාන්ස්-අප්රිකානු මහාමාර්ග ජාලයේ මාර්ග තුනක් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හරහා ගමන් කරයි:

- ට්රිපොලි-කේප් ටවුන් අධිවේගී මාර්ගය: මෙම මාර්ගය රටේ බටහිර අන්තය හරහා ජාතික මාර්ග අංක 1 හි කිංෂාසා සහ මටාඩි අතර, සාධාරණ තත්ත්වයේ ඇති එකම පදික කොටසකින් කිලෝමීටර 285 (සැතපුම් 177) දුරින් ගමන් කරයි.

- ලාගෝස්-මොම්බාසා අධිවේගී මාර්ගය: කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය යනු මෙම නැගෙනහිර-බටහිර අධිවේගී මාර්ගයේ ඇති ප්රධාන අවසන් අන්තයක් වන අතර එම නිසා නව මාර්ගයක් ඉදිකිරීමට අවශ්ය වේ.

- බීරා-ලොබිටෝ අධිවේගී මාර්ගය: මෙම නැගෙනහිර-බටහිර අධිවේගී මාර්ගය කටන්ගා හරහා ගමන් කරන අතර, කොල්වේසි සහ ලුබුම්බෂි අතර ඉතා දුර්වල තත්ත්වයේ ඇති මාර්ගයක් සහ එහි දිගින් වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් නැවත ඉදිකිරීම අවශ්ය වේ. සැම්බියානු දේශසීමාවට කෙටි දුරින් සාධාරණ තත්ත්වයේ මාර්ගයක් ඇත.

ජලය

[සංස්කරණය]කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතුව කිලෝමීටර් දහස් ගණනක් යාත්රා කළ හැකි ජල මාර්ග තිබේ. සම්ප්රදායිකව ජල ප්රවාහනය රටේ දළ වශයෙන් තුනෙන් දෙකක පමණ එහා මෙහා ගමන් කිරීමේ ප්රමුඛ මාධ්යය වී ඇත.

ගුවන්

[සංස්කරණය]2016 වන විට, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය තුළ ගුවන් ගමන් පිරිනමන එක් ප්රධාන ජාතික ගුවන් සේවයක් (Congo Airways) තිබුණි. කොංගෝ එයාර්වේස් කින්ෂාසා ජාත්යන්තර ගුවන් තොටුපළේ පිහිටා ඇත. ප්රමාණවත් ආරක්ෂක ප්රමිතීන් නොමැති නිසා කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය විසින් සහතික කරන ලද සියලුම ගුවන් ප්රවාහකයන් යුරෝපීය කොමිසම විසින් යුරෝපා සංගමයේ ගුවන් තොටුපලවලින් තහනම් කර ඇත.[186]

ජාත්යන්තර ගුවන් සමාගම් කිහිපයක් කිංෂාසා හි ජාත්යන්තර ගුවන් තොටුපළට සේවා සපයන අතර කිහිපයක් ලුබුම්බෂි ජාත්යන්තර ගුවන් තොටුපළ වෙත ජාත්යන්තර ගුවන් ගමන් සපයයි.

බලශක්තිය

[සංස්කරණය]ගල් අඟුරු සහ බොරතෙල් සම්පත් යන දෙකම 2008 දක්වා දේශීය වශයෙන් භාවිතා කරන ලදී. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතුව ඉන්ගා වේලි අසල කොංගෝ ගඟේ ජල විදුලිය සඳහා යටිතල පහසුකම් ඇත.[187] රටේ උපායමාර්ගික වැදගත්කම සහ මධ්යම අප්රිකාවේ ආර්ථික බලවතෙකු ලෙස එහි විභව භූමිකාව පිළිබඳ එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ වාර්තාවකට අනුව, අප්රිකාවේ වනාන්තරවලින් 50% ක් සහ මුළු මහාද්වීපයටම ජල විදුලි බලය සැපයිය හැකි ගංගා පද්ධතියක් ද රට සතුව ඇත.[188]

විදුලිය නිපදවීම සහ බෙදා හැරීම Société Nationale d'électricité විසින් පාලනය කරනු ලබන නමුත් විදුලිය ලබා ගත හැක්කේ රටෙන් 15% කට පමණි.[189] කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය විදුලි බල තටාක තුනක සාමාජිකයෙකි. එනම් දකුණු අප්රිකානු බල සංචිතය, නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු බල සංචිතය සහ මධ්යම අප්රිකානු බල සංචිතයයි.

පුනර්ජනනීය බලශක්තිය

[සංස්කරණය]බහුල හිරු එළිය නිසා, සූර්ය සංවර්ධනය සඳහා ඇති හැකියාව කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ඉතා ඉහළ ය. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි දැනටමත් සූර්ය බලශක්ති පද්ධති 836 ක් පමණ ඇති අතර, සම්පූර්ණ බලය 83 MW වන අතර, ඉක්වදෝර් (167), කටන්ගා (159), නෝර්ඩ්-කිවු (170), කසායි පළාත් දෙක (170) සහ බාස්-කොංගෝ (170) ලෙස පිහිටා ඇත. එසේම, 148 කැරිටාස්ජාල පද්ධතියෙහි සම්පූර්ණ බලය 6.31 MW වේ.[190]

ජනවිකාශනය

[සංස්කරණය]ජනගහනය

[සංස්කරණය]

CIA World Factbook 2023 වන විට ජනගහනය මිලියන 111 ඉක්මවන බව ගණන් බලා ඇත.[191] 1950 සහ 2000 අතර, රටේ ජනගහනය මිලියන 12.2 සිට මිලියන 46.9 දක්වා හතර ගුණයකින් වැඩි විය.[192]

භාෂා

[සංස්කරණය]

ප්රංශ යනු කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ නිල භාෂාවයි. එය කොංගෝවේ විවිධ ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම් අතර සන්නිවේදනය සඳහා පහසුකම් සලසමින් භාෂා භාෂාව ලෙස සංස්කෘතික වශයෙන් පිළිගැනේ. 2018 OIF වාර්තාවකට අනුව, මිලියන 49 ක කොංගෝ ජනතාව (ජනගහනයෙන් 51%) ප්රංශ භාෂාවෙන් කියවීමට සහ ලිවීමට හැකිය.[193] 2021 සමීක්ෂණයකින් හෙළි වූයේ ජනගහනයෙන් 74% කට ප්රංශ භාෂාව කතා කළ හැකි බවත්, එය රටේ වැඩිපුරම කතා කරන භාෂාව බවට පත් කරන බවත්ය.[194]

කිංෂාසා හි, 2014 දී ජනගහනයෙන් 67% කට ප්රංශ කියවීමට සහ ලිවීමට හැකි වූ අතර 68.5% කට එය කථා කිරීමට සහ තේරුම් ගැනීමට හැකි විය.[195]

රට තුළ භාෂා 242 ක් පමණ කතා කරන අතර, ඉන් හතරකට ජාතික භාෂා තත්ත්වය ඇත: කිටුබා (කිකොන්ගෝ), ලිංගාලා, ෂිලුබා සහ ස්වහීලී. සමහර සීමිත පුද්ගලයින් සංඛ්යාවක් මේවා පළමු භාෂා ලෙස කතා කළත්, ජනගහනයෙන් බහුතරයක් ඒවා තම ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායමේ මව් භාෂාවෙන් පසුව දෙවන භාෂාව ලෙස කතා කරයි. බෙල්ජියම් යටත් විජිත පාලනය යටතේ ලිංගාලා ෆෝස් පබ්ලික්හි නිල භාෂාව වූ අතර අද දක්වා සන්නද්ධ හමුදාවන්ගේ ප්රමුඛ භාෂාව ලෙස පවතී. මෑත කැරලි වලින් පසු, නැගෙනහිර හමුදාවේ හොඳ කොටසක් ස්වහීලී භාෂාව භාවිතා කරයි, එහිදී එය කලාපීය භාෂා භාෂාව වීමට තරඟ කරයි.

බෙල්ජියම් පාලනය යටතේ, බෙල්ජියම් ජාතිකයන් ප්රාථමික පාසල්වල ජාතික භාෂා හතර ඉගැන්වීම සහ භාවිතය ආරම්භ කළ අතර, යුරෝපීය යටත් විජිත සමයේ දේශීය භාෂා පිළිබඳ සාක්ෂරතාව තිබූ අප්රිකානු ජාතීන් කිහිපයෙන් එකක් බවට එය පත් විය. නිදහසින් පසු මෙම ප්රවණතාවය ආපසු හැරවිය, ඒ ප්රංශ භාෂාව සියලු මට්ටම්වල අධ්යාපනයේ එකම භාෂාව බවට පත් වූ විටය.[196] 1975 සිට, ප්රාථමික අධ්යාපනයේ පළමු වසර දෙක තුළ ජාතික භාෂා හතර නැවත හඳුන්වා දී ඇති අතර, තුන්වන වසරේ සිට ප්රංශ අධ්යාපනයේ එකම භාෂාව බවට පත් විය, නමුත් ප්රායෝගිකව නාගරික ප්රදේශවල බොහෝ ප්රාථමික පාසල් ප්රංශ භාවිතා කරන්නේ පළමු වසරේ සිටය.[196] පෘතුගීසි භාෂාව විදේශීය භාෂාවක් ලෙස කොංගෝ පාසල්වල උගන්වනු ලැබේ. ප්රංශ භාෂාව සමඟ ඇති ශබ්දකෝෂ සමානතාවය සහ ශබ්ද විද්යාව පෘතුගීසි භාෂාව මිනිසුන්ට ඉගෙන ගැනීමට සාපේක්ෂව පහසු භාෂාවක් බවට පත් කරයි. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි දළ වශයෙන් 175,000 පෘතුගීසි කථිකයන්ගෙන් වැඩි දෙනෙක් ඇන්ගෝලියානු සහ මොසැම්බිකානු විදේශිකයන් වේ.

ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම්

[සංස්කරණය]ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම් 250කට වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් සහ ගෝත්ර 450ක් (ජනවාර්ගික උප කණ්ඩායම්) කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි වාසය කරයි. ඔවුන් බන්ටු, සුඩානික්, නිලෝටික්, උබන්ජියන් සහ පිග්මි යන භාෂාමය කණ්ඩායම් වලට අයත් වේ. මෙම විවිධත්වය නිසා කොංගෝවේ ප්රමුඛ ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායමක් නොමැත, කෙසේ වෙතත් පහත ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම් ජනගහනයෙන් 51.5% ක් නියෝජනය කරයි:[197]

- ලුබා-කසායි

- කොංගෝ

- මොංගෝ

- ලුබකට්

- ලුලුවා

- ටෙටෙලා

- නන්දේ

- න්ග්බැන්ඩි

- න්ගොම්බේ

- යකා

- න්ග්බාකා

2021 දී, එක්සත් ජාතීන් විසින් රටේ ජනගහනය මිලියන 96 ක් ලෙස ඇස්තමේන්තු කරන ලද අතර,[198][199] එය පවතින යුද්ධය නොතකා 1992 දී මිලියන 39.1 සිට වූ වේගවත් වර්ධනයකි.[200] ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම් 250 ක් පමණ හඳුනාගෙන නම් කර ඇත. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි පිග්මිවරුන් 600,000 ක් පමණ ජීවත් වෙති.[201]

ආගම්

[සංස්කරණය]

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ප්රමුඛතම ආගම ක්රිස්තියානි ධර්මයයි. 2013-2014 ජනවිකාශනය සහ සෞඛ්ය සමීක්ෂණ වැඩසටහන මගින් පවත්වන ලද 2013-14 සමීක්ෂණයකින් පෙන්නුම් කළේ ජනගහනයෙන් 93.7% කිතුනුවන් (කතෝලිකයන් 29.7%, රෙපරමාදු භක්තිකයින් 26.8% සහ අනෙකුත් කිතුනුවන් 37.2%) සමන්විත බවයි. නව ක්රිස්තියානි ආගමික ව්යාපාරයක් වන කිම්බංගුවාදය හි 2.8% ක් අනුගත වූ අතර මුස්ලිම්වරුන් 1% කි.[202]

අනෙකුත් මෑත ඇස්තමේන්තු මගින් ක්රිස්තියානි ධර්මය බහුතර ආගම ලෙස සොයාගෙන ඇති අතර, 2010 Pew පර්යේෂණ මධ්යස්ථාන ඇස්තමේන්තුවකට අනුව[203] ජනගහනයෙන් 95.8% ක් අනුගමනය කරන අතර CIA World Factbook මෙම අගය 95.9% ක් ලෙස වාර්තා කරයි.[204] ඉස්ලාම් අනුගාමිකයින්ගේ අනුපාතය 1%[205] සිට 12%[206] දක්වා විවිධ ලෙස ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇත.

අගරදගුරු පදවි හයක් සහ රදගුරු පදවි 41ක් සමඟ රට තුළ කතෝලිකයන් මිලියන 35ක් පමණ සිටිති.[7] කතෝලික පල්ලියේ බලපෑම අධිතක්සේරු කිරීම දුෂ්කර ය. ෂැට්ස්බර්ග් එය හැඳින්වූයේ රටේ "රාජ්ය හැරුණු විට එකම සැබෑ ජාතික ආයතනය" ලෙසය.[10] එහි පාසල් වල ප්රාථමික පාසල් සිසුන්ගෙන් 60% කට වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් සහ එහි ද්විතීයික සිසුන්ගෙන් 40% කට වඩා අධ්යාපනය ලබා ඇත. පල්ලිය සතුව පුළුල් රෝහල්, පාසල් සහ සායන ජාලයක් මෙන්ම ගොවිපලවල්, ගොවිපලවල්, වෙළඳසැල් සහ ශිල්පීන්ගේ සාප්පු ඇතුළු බොහෝ රදගුරු ආර්ථික ව්යවසායන් ද හිමිකරගෙන කළමනාකරණය කරයි.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

ප්රොතෙස්තන්ත නිකායන් හැට දෙකක් කොංගෝවේ ක්රිස්තු දේවස්ථානයේ කුඩය යටතේ සංධානගත වේ. එය බොහෝ විට කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය රෙපරමාදු භක්තිකයන් ආවරණය වන බැවින් එය බොහෝ විට රෙපරමාදු පල්ලිය ලෙස හැඳින්වේ. සාමාජිකයින් මිලියන 25කට වඩා වැඩි සංඛ්යාවක් සිටින එය ලොව විශාලතම රෙපරමාදු සංවිධානයන්ගෙන් එකකි.

කිම්බංගුවාදය යටත් විජිත පාලනයට තර්ජනයක් ලෙස සලකනු ලැබූ අතර එය බෙල්ජියම්වරුන් විසින් තහනම් කරන ලදී. කිම්බංගුවාදය, නිල වශයෙන් "අනාගතවක්තෘ සයිමන් කිම්බංගු විසින් පෘථිවිය මත ක්රිස්තුස් වහන්සේගේ සභාව" ලෙස හැදින්වේ,[207] මූලික වශයෙන් මධ්යම කොන්ගෝව සහ කිංෂාසා හි බකොන්ගෝ අතර සාමාජිකයින් මිලියන තුනක් පමණ ඇත.

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ 18 වැනි සියවසේ සිට, නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාවේ අරාබි වෙළඳුන් ඇත් දත් සහ වහල් වෙළඳාම සඳහා අභ්යන්තරයට තල්ලු කළ විට ඉස්ලාම් ආගම පවතී. අද, Pew පර්යේෂණ මධ්යස්ථානයට අනුව මුස්ලිම්වරුන් කොංගෝ ජනගහනයෙන් ආසන්න වශයෙන් 1% කි. බහුතරය සුන්නි මුස්ලිම්වරු.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

රට තුළ ජීවත් වූ බහායි ඇදහිල්ලේ පළමු සාමාජිකයන් පැමිණියේ 1953 දී උගන්ඩාවෙනි. වසර හතරකට පසු පළමු ප්රාදේශීය පරිපාලන සභාව තේරී පත් විය. 1970 දී ජාතික අධ්යාත්මික සභාව (ජාතික පරිපාලන සභාව) මුලින්ම තේරී පත් විය. 1970 ගණන්වල සහ 1980 ගණන්වල ආගම තහනම් කළත්, විදේශීය ආණ්ඩු වැරදි ලෙස නිරූපණය කිරීම නිසා, 1980 දශකය අවසන් වන විට තහනම ඉවත් කරන ලදී. 2012 දී රට තුළ ජාතික බහායි නමස්කාර මන්දිරයක් ඉදිකිරීමට සැලසුම් කරන ලදී.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

සාම්ප්රදායික ආගම් ඒකදේවවාදය, සජීවීවාදය, ජීවවාදය, ආත්මය සහ මුතුන්මිත්තන්ගේ නමස්කාරය, මායා කර්මය සහ මන්තර ගුරුකම් වැනි සංකල්ප මූර්තිමත් කරන අතර වාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම් අතර පුළුල් ලෙස වෙනස් වේ. සමමුහුර්ත නිකායන් බොහෝ විට ක්රිස්තියානි ධර්මයේ අංග සම්ප්රදායික විශ්වාසයන් සහ චාරිත්ර වාරිත්ර සමඟ ඒකාබද්ධ කරන අතර ප්රධාන ධාරාවේ පල්ලි විසින් ක්රිස්තියානි ධර්මයේ කොටසක් ලෙස පිළිගනු නොලැබේ. විශේෂයෙන්ම ළමයින්ට සහ වැඩිහිටියන්ට එරෙහිව මායා කර්ම චෝදනා සම්බන්ධයෙන් පෙරමුණ ගෙන සිටින එක්සත් ජනපදයේ ආනුභාව ලත් පෙන්තකොස්ත පල්ලි විසින් මෙහෙයවන ලද පුරාණ විශ්වාසයන්ගේ නව ප්රභේදයන් පුළුල් ලෙස ව්යාප්ත වී ඇත.[පැහැදීම ඇවැසිය][208] මන්ත්ර ගුරුකම් සම්බන්ධයෙන් චෝදනා එල්ල වූ දරුවන් නිවෙස්වලින් සහ පවුලෙන් පිටමං කරනු ලබන අතර, බොහෝ විට පාරේ ජීවත් වීමට යවනු ලබන අතර, මෙම දරුවන්ට එරෙහිව ශාරීරික හිංසනයට හේතු විය හැක.[209][පැහැදීම ඇවැසිය][210] කොංගෝ ළමා භාරය වැනි වීදි දරුවන්ට ආධාර කරන පුණ්යායතන තිබේ.[211] කොංගෝ ළමා භාරයේ ප්රමුඛතම ව්යාපෘතිය වන්නේ ලුබුම්බාෂි හි වීදි දරුවන් නැවත එක් කිරීමට ක්රියා කරන කිම්බිලියෝ ය.[212] මෙම ළමුන් සඳහා සාමාන්ය යෙදුම වන්නේ enfants sorciers (ළමා මායාකාරියන්) හෝ enfants dits sorciers (මායාකාරියන් සම්බන්ධයෙන් චෝදනා ලැබූ ළමුන්) යන්නයි. මෙම විශ්වාසය ප්රයෝජනයට ගැනීමට නිකායට අයත් නොවන පල්ලි සංවිධාන පිහිටුවාගෙන ඇත්තේ භූතයන් දුරුකිරීම සඳහා අධික මුදලක් අයකරමිනි. මෑතකදී නීතියෙන් තහනම් කර ඇතත්, මෙම භූතයන් දුරු කිරීම සඳහා ළමුන් බොහෝ විට ප්රචණ්ඩකාරී අපයෝජනයන්ට ලක්ව ඇත්තේ ස්වයං ප්රකාශිත අනාගතවක්තෘවරුන් සහ පූජකයන් අතින්.[213]

අධ්යාපනය

[සංස්කරණය]

2014 දී, DHS ජාතික සමීක්ෂණයකට අනුව වයස අවුරුදු 15 සහ 49 අතර ජනගහනයේ සාක්ෂරතා අනුපාතය 75.9% (පිරිමි 88.1% සහ 63.8% කාන්තා) ලෙස ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇත.[214] අධ්යාපන ක්රමය පාලනය වන්නේ රජයේ අමාත්යාංශ තුනකිනි: අමාත්යවරයා, ද්විතීයික සහ වෘත්තිකයින් (MEPSP), අමාත්යවරයා ද l'Enseignement Supérieur et Universitaire (MESU) සහ Ministère des Affaires සමාජීය. කොංගෝ ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාවේ එය එසේ විය යුතු බව පැවසුවද[215] (2005 කොංගෝ ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාවේ 43 වැනි වගන්තිය) ප්රාථමික අධ්යාපනය නොමිලයේ හෝ අනිවාර්ය නොවේ.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

1990 ගණන්වල අග භාගයේ - 2000 ගණන්වල මුල් භාගයේ පළමු සහ දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධවල ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස, රටේ ළමුන් මිලියන 5.2 කට වැඩි පිරිසකට කිසිදු අධ්යාපනයක් නොලැබුණි.[216] සිවිල් යුද්ධය අවසන් වීමෙන් පසුව, යුනෙස්කෝවට අනුව, ප්රාථමික පාසල්වලට ඇතුළත් වූ ළමුන් සංඛ්යාව 2002 දී මිලියන 5.5 සිට 2018 මිලියන 16.8 දක්වා ඉහළ යාමත් සමඟ හා 2007 දී ද්විතීයික පාසල්වලට ඇතුළත් වූ ළමුන් සංඛ්යාව මිලියන 2.8 සිට 2015 දී මිලියන 4.6 දක්වා ඉහළ යාමත් සමඟ තත්ත්වය විශාල ලෙස වැඩිදියුණු වී ඇත.[217]

ප්රාථමික පාසල්වල ශුද්ධ පැමිණීම 2014 දී 82.4%ක් ලෙස ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇති පරිදි මෑත වසරවලදී සැබෑ පාසල් පැමිණීමද විශාල ලෙස වර්ධනය වී ඇත (වයස අවුරුදු 6-11 දක්වා ළමුන් පාසල් ගොස් 82.4%; පිරිමි ළමුන් සඳහා 83.4%, ගැහැණු ළමුන් සඳහා 80.6%).[218]

සෞඛ්ය

[සංස්කරණය]

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි රෝහල්වලට කිංෂාසා මහ රෝහල ඇතුළත් වේ. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ළදරු මරණ අනුපාතය (චැඩ්ට පසුව) ලෝකයේ දෙවන ඉහළම අනුපාතය ඇත. 2011 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී, එන්නත් සඳහා ගෝලීය සන්ධානය හි ආධාර හරහා, නියුමොකොකල් රෝග වැළැක්වීම සඳහා නව එන්නතක් කිංෂාසා වටා හඳුන්වා දෙන ලදී.[219] 2012 දී ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇත්තේ වයස අවුරුදු 15-49 අතර වැඩිහිටියන්ගෙන් 1.1% ක් පමණ HIV/AIDS සමඟ ජීවත් වන බවයි.[220] මැලේරියාව[221][222] සහ කහ උණ ගැටළු වේ.[223] 2019 මැයි මාසයේදී කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ඉබෝලා පැතිර යාමෙන් මියගිය සංඛ්යාව 1,000 ඉක්මවා ගියේය.[224]

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි කහ උණ ආශ්රිත මරණ සංඛ්යාව සාපේක්ෂව අඩුය. ලෝක සෞඛ්ය සංවිධානයේ (WHO) 2021 වාර්තාවට අනුව, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි කහ උණ හේතුවෙන් ජීවිත අහිමි වූයේ පුද්ගලයන් දෙදෙනෙකුට පමණි.[225]

ලෝක බැංකු සමූහයට අනුව, 2016 දී රථවාහන අනතුරු හේතුවෙන් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි මාර්ගවල පුද්ගලයින් 26,529 දෙනෙකුට ජීවිත අහිමි විය.[226]

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි මාතෘ සෞඛ්ය දුර්වලයි. 2010 ඇස්තමේන්තු වලට අනුව, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ලෝකයේ 17 වන ඉහළම මාතෘ මරණ අනුපාතය ඇත.[227] යුනිසෙෆ් සංවිධානයට අනුව වයස අවුරුදු පහට අඩු ළමුන්ගෙන් 43.5% ක් වර්ධනය අඩාල වීමේ තත්ත්වයට පත්ව ඇත.[228]

එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ හදිසි ආහාර සහන ඒජන්සිය අනතුරු ඇඟවූයේ කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි COVID-19 න් පසු උත්සන්න වන ගැටුම් සහ නරක අතට හැරෙන තත්ත්වය මධ්යයේ, කුසගින්නෙන් මිය යා හැකි බැවින් මිලියන සංඛ්යාත ජීවිත අවදානමට ලක්ව ඇති බවයි. ලෝක ආහාර වැඩසටහනේ දත්ත වලට අනුව, 2020 දී කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි පුද්ගලයන් දස දෙනෙකුගෙන් හතර දෙනෙකුට ආහාර සුරක්ෂිතතාවක් නොමැති අතර මිලියන 15.6 ක් පමණ සාගින්න අර්බුදයකට මුහුණ දී සිටිති.[229]

කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ වායු දූෂණ මට්ටම ඉතා සෞඛ්යයට අහිතකරයි. 2020 දී, කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ වාර්ෂික සාමාන්ය වායු දූෂණය 34.2 µg/m³ විය, එය ලෝක සෞඛ්ය සංවිධානයේ PM2.5 මාර්ගෝපදේශය මෙන් 6.8 ගුණයකට ආසන්නය (5 µg/m³: 2021 සැප්තැම්බර් මාසයේදී සකසා ඇත).[230] මෙම දූෂණ මට්ටම් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි සාමාන්ය පුරවැසියෙකුගේ ආයු අපේක්ෂාව වසර 2.9 කින් පමණ අඩු කිරීමට ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇත.[230] දැනට, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය සතුව ජාතික පරිසර වායු තත්ත්ව ප්රමිතියක් නොමැත.[231]

විශාලතම නගර

[සංස්කරණය]| ස්ථානය | පළාත | ජනගහණය | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

කිංෂාසා  ම්බුජි-මයි |

1 | කිංෂාසා | කිංෂාසා | 15,628,000 |  ලුබුම්බෂි  කනංග | ||||

| 2 | ම්බුජි-මයි | කසායි-පෙරදිග | 2,765,000 | ||||||

| 3 | ලුබුම්බෂි | හවුට්-කටන්ගා | 2,695,000 | ||||||

| 4 | කනංග | කසායි-මධ්යම | 1,593,000 | ||||||

| 5 | කිසංගනී | ටෂොපෝ | 1,366,000 | ||||||

| 6 | බුකාවු | දකුණු කිවු | 1,190,000 | ||||||

| 7 | ත්ෂිකාපා | කසායි | 1,024,000 | ||||||

| 8 | බුනියා | ඉටුරි | 768,000 | ||||||

| 9 | ගෝමා | උතුරු කිවු | 707,000 | ||||||

| 10 | උවිර | දකුණු කිවු | 657,000 | ||||||

සංක්රමණය

[සංස්කරණය]

රටේ බොහෝ විට අස්ථායී තත්ත්වය සහ රාජ්ය ව්යුහයන්ගේ තත්ත්වය අනුව, විශ්වසනීය සංක්රමණ දත්ත ලබා ගැනීම අතිශයින් දුෂ්කර ය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, සාක්ෂිවලින් පෙනී යන්නේ සංක්රමණිකයන්ගේ සංඛ්යාවේ මෑත කාලීන අඩුවීම් තිබියදීත්, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ඔවුන් සඳහා ගමනාන්ත රටක් ලෙස දිගටම පවතින බවයි. සංක්රමණය ස්වභාවයෙන්ම ඉතා විවිධවේ; සරණාගතයින් මහා විල් කලාපයේ නොයෙකුත් සහ ප්රචණ්ඩ ගැටුම් වල නිෂ්පාදන හා ජනගහනයේ වැදගත් උප කුලකයක් වේ. මීට අමතරව, රටේ විශාල පතල් මෙහෙයුම් අප්රිකාවෙන් සහ ඉන් ඔබ්බෙන් සංක්රමණික කම්කරුවන් ආකර්ෂණය කරයි. අනෙකුත් අප්රිකානු රටවලින් සහ ලෝකයේ සෙසු ප්රදේශවලින් වාණිජ කටයුතු සඳහා සැලකිය යුතු සංක්රමණයක් ද ඇත, නමුත් මෙම චලනයන් හොඳින් අධ්යයනය කර නොමැත.[234] දකුණු අප්රිකාව සහ යුරෝපය දෙසට සංක්රමණ සංක්රමණය ද භූමිකාවක් සිදුවේ.

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වෙත සංක්රමණය වීම පසුගිය දශක දෙක තුළ ක්රමානුකූලව අඩු වී ඇති අතර, බොහෝ විට රට අත්විඳින ලද සන්නද්ධ ප්රචණ්ඩත්වයේ ප්රතිඵලයක් විය හැකිය. සංක්රමණ සඳහා වූ ජාත්යන්තර සංවිධානයට අනුව, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි සංක්රමණිකයන් සංඛ්යාව 1960 දී යන්තම් මිලියනයකට වඩා අඩු වී ඇති අතර, 1990 දී 754,000 දක්වා ද, 2005 දී 480,000 දක්වා ද, 2010 දී ඇස්තමේන්තුගත 445,000 දක්වා ද පහත වැටී ඇත. අක්රමවත් සංක්රමණිකයන් පිළිබඳ දත්ත ද නොමැත, කෙසේ වෙතත් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ජාතිකයන් සමඟ අසල්වැසි රටවල ජනවාර්ගික සබඳතා සැලකිල්ලට ගෙන, අක්රමවත් සංක්රමණය සැලකිය යුතු සංසිද්ධියක් ලෙස උපකල්පනය කෙරේ.[234]

විදේශයන්හි කොංගෝ ජාතිකයන් සඳහා සංඛ්යා ප්රභවය අනුව මිලියන තුනේ සිට හය දක්වා විශාල වශයෙන් වෙනස් වේ. මෙම විෂමතාවය නිල, විශ්වසනීය දත්ත නොමැතිකම නිසාය. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වෙතින් පැමිණෙන සංක්රමණිකයන් සියල්ලටම වඩා දිගුකාලීන සංක්රමණිකයන් වන අතර, ඔවුන්ගෙන් බහුතරය අප්රිකාවේ සහ අඩු ප්රමාණයකට යුරෝපයේ ජීවත් වෙති; ඇස්තමේන්තුගත 2000 දත්ත වලට අනුව පිළිවෙලින් 79.7% සහ 15.3%. නව ගමනාන්ත රටවලට දකුණු අප්රිකාව සහ යුරෝපයට යන මාර්ගයේ විවිධ ස්ථාන ඇතුළත් වේ. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය කලාපයේ සහ ඉන් ඔබ්බෙහි පිහිටි සරණාගතයින් සැලකිය යුතු සංඛ්යාවක් බිහි කර ඇත. UNHCR ට අනුව, කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය වෙතින් සරණාගතයින් 460,000 කට වඩා වැඩි සංඛ්යාවක් සිටින විට මෙම සංඛ්යාව 2004 දී ඉහළ ගියේය. 2008 දී කොංගෝ සරණාගතයින් 367,995 ක් වූ අතර ඔවුන්ගෙන් 68% ක් වෙනත් අප්රිකානු රටවල ජීවත් වූහ.[234]

2003 වසරේ සිට කොංගෝ සංක්රමණිකයන් 400,000කට වැඩි පිරිසක් ඇන්ගෝලාවෙන් නෙරපා හැර ඇත.[235]

සංස්කෘතිය

[සංස්කරණය]

සංස්කෘතිය එහි විවිධ ජනවාර්ගික කණ්ඩායම්වල විවිධත්වය සහ රට පුරා ඔවුන්ගේ විවිධ ජීවන රටාවන් පිළිබිඹු කරයි - වෙරළ තීරයේ කොංගෝ ගඟේ මුඛයේ සිට, වැසි වනාන්තරය හරහා ඉහළට සහ එහි මධ්යයේ සැවානා හරහා, ඈත ජනාකීර්ණ කඳුකරය දක්වා. නැගෙනහිර. 19 වන සියවසේ අග භාගයේ සිට, සාම්ප්රදායික ජීවන ක්රම යටත් විජිතවාදය, නිදහස සඳහා වූ අරගලය, මොබුටු යුගයේ එකතැන පල්වීම සහ වඩාත් මෑතදී පළමු සහ දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධ විසින් ගෙන එන ලද වෙනස්කම් වලට භාජනය වී ඇත. මෙම බලපෑම් මධ්යයේ වුවද, කොංගෝවේ චාරිත්ර වාරිත්ර සහ සංස්කෘතීන් ඔවුන්ගේ පෞද්ගලිකත්වය බොහෝ දුරට රඳවාගෙන ඇත. රටේ මිලියන 81ක වැසියන් (2016) ප්රධාන වශයෙන් ග්රාමීය වේ. නාගරික ප්රදේශවල ජීවත් වන 30% බටහිර බලපෑම්වලට වඩාත්ම විවෘත වී ඇත.

සංගීතය

[සංස්කරණය]කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි කියුබානු රුම්බා, මුලින් කොංගෝවේ කුම්බා සහ මෙරෙන්ගු කෙරෙහි එහි බලපෑම් ඇත. ඒ දෙන්නා පසුව සුකස් බිහි කරනවා.[236] අනෙකුත් අප්රිකානු ජාතීන් කොංගෝ සෝකස් වෙතින් ලබාගත් සංගීත ප්රභේද නිෂ්පාදනය කරයි. සමහර අප්රිකානු සංගීත කණ්ඩායම් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ප්රධාන භාෂාවක් වන ලිංගාලා භාෂාවෙන් ගායනා කරති. "le sapeur", පපා වෙම්බා ගේ මගපෙන්වීම යටතේ, එම කොංගෝ ජාතික සුකස්, සෑම විටම මිල අධික මෝස්තර ඇඳුම් වලින් සැරසී සිටින තරුණ පරම්පරාවක් සඳහා ස්වරය සකසා ඇත. ඔවුන් කොංගෝ සංගීතයේ සිව්වන පරම්පරාව ලෙස හඳුන්වනු ලැබූ අතර බොහෝ විට පැමිණෙන්නේ හිටපු සුප්රසිද්ධ සංගීත කණ්ඩායමක් වන වෙන්ගේ සංගීත කණ්ඩායමෙනි. දැන් එංගලන්තයේ ජීවත් වන සංගීත කලාකරු එලිසෝ කිසොංගා, මුලින් කොංගෝවේ සිට ඇත.

ක්රීඩා

[සංස්කරණය]පාපන්දු, පැසිපන්දු සහ රග්බි ඇතුළු බොහෝ ක්රීඩා කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ක්රීඩා කෙරේ. ස්ටේඩ් ෆෙඩ්රික් කිබස්සා මලිබා ඇතුළුව රට පුරා ක්රීඩාංගණ ගණනාවක ක්රීඩා කරනු ලැබේ.[237] සයරේ ලෙස ඔවුන් 1974 FIFA ලෝක කුසලානයට සහභාගී විය.

ජාත්යන්තර වශයෙන්, රට එහි වෘත්තීය පැසිපන්දු NBA සහ පාපන්දු ක්රීඩකයින් සඳහා විශේෂයෙන් ප්රසිද්ධය. ඩිකෙම්බේ මුටොම්බෝ යනු මෙතෙක් ක්රීඩා කළ හොඳම අප්රිකානු පැසිපන්දු ක්රීඩකයෙකි. මුටොම්බෝ ඔහුගේ මව් රටේ මානුෂීය ව්යාපෘති සඳහා ප්රසිද්ධය. බිස්මැක් බයියොම්බෝ, ක්රිස්ටියන් අයෙන්ගා, ජොනතන් කුමින්ගා සහ එමානුවෙල් මුඩියායි පැසිපන්දු ක්රීඩාවේ සැලකිය යුතු ජාත්යන්තර අවධානයක් දිනාගත් තවත් අය වෙති. කොංගෝ ක්රීඩකයින් සහ කොන්ගෝ සම්භවයක් ඇති ක්රීඩකයින් කිහිප දෙනෙකු - ප්රහාරක රොමේලු ලුකාකු, යානික් බොලැසි සහ ඩියුමර්සි ම්බොකානි - ලෝක පාපන්දු ක්රීඩාවේ ප්රමුඛත්වය ලබා ගෙන ඇත. කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය අප්රිකානු ජාතීන්ගේ කුසලාන පාපන්දු තරඟාවලිය දෙවරක් දිනා ඇත.

කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය කාන්තා ජාතික වොලිබෝල් කණ්ඩායම අවසන් වරට 2021 කාන්තා අප්රිකානු ජාතීන්ගේ වොලිබෝල් ශූරතාවලිය සඳහා සුදුසුකම් ලබා ඇත.[238] 2018-2020 CAVB බීච් වොලිබෝල් මහද්වීපික කුසලානයට කාන්තා සහ පිරිමි යන අංශ දෙකෙන්ම තරඟ කළ ජාතික කණ්ඩායමක් බීච් වොලිබෝල් ක්රීඩාවේ රට නියෝජනය කළේය.[239]

මාධ්ය

[සංස්කරණය]කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි පුවත්පත් අතර L'Avenir, Radion Télévision Mwangaza, Le Phare, Le Potentiel, Le Soft සහ LeCongolais.CD[240], දිනපතා වෙබ් පාදක වේ.[241] Radio Télévision Nationale Congolaise (RTNC) යනු කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ ජාතික විකාශකයා වේ. RTNC දැනට ලිංගාලා, ප්රංශ සහ ඉංග්රීසි භාෂාවෙන් විකාශනය කරයි.

සාහිත්යය

[සංස්කරණය]කොංගෝ කතුවරුන් කොන්ගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය හි ජනතාව අතර ජාතික විඥානය පිළිබඳ හැඟීමක් වර්ධනය කිරීමේ මාර්ගයක් ලෙස සාහිත්යය භාවිතා කරයි. ෆෙඩ්රික් කම්බෙම්බා යමුසාංගී කොංගෝවේ හැදී වැඩුණු පරම්පරා අතර, ඔවුන් යටත් විජිතයක් වූ කාලයේ, නිදහස සඳහා සටන් කරමින් සහ ඉන් පසුව සාහිත්ය ලියයි. යමුසාංගී සම්මුඛ සාකච්ඡාවකදී[242] කියා සිටියේ තමාට සාහිත්යයේ දුරස්ථභාවය දැනුණු බවත්, සම්පූර්ණ කවය නම් නවකතාව තමා රචනා කළ බවට පිළියමක් අවශ්ය බවත්ය, එය පොතේ ආරම්භයේ දී විවිධ කණ්ඩායම් අතර සංස්කෘතියේ වෙනසක් දැනෙන එමානුවෙල් නම් පිරිමි ළමයෙකුගේ කතාවකි.[243] කටන්ගා පළාතේ කතුවරයකු වන රයිස් නෙසා බොනේසා, ගැටුම් ආමන්ත්රණය කිරීමට සහ ඒවා සමඟ කටයුතු කිරීමට මාර්ගයක් ලෙස කලාත්මක ප්රකාශන ප්රවර්ධනය කිරීම සඳහා නවකතා සහ කවි ලිවීය.[244]

සටහන්

[සංස්කරණය]- ^ The term "Kikongo" in the Constitution is actually referring to the Kituba language – which is known as Kikongo ya leta by its speakers – not the Kongo language proper. The confusion arises from the fact that the government of the DRC officially recognizes and refers to the language as "Kikongo".

- ^ In terms of annual carats produced

- ^ The figures are obtained by dividing the population figures in the Wikipedia country articles by the paved roads figure in the 'Transport in [country]' articles.

යොමු කිරීම්

[සංස්කරණය]- ^ "Democratic Republic of the Congo". United States Department of State. 2022-06-02. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-03-23.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency (2014). "Democratic Republic of the Congo". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency. 22 February 2021 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Congo, Democratic Republic of the". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 September 2022. (Archived 2022 edition)

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 2022. සම්ප්රවේශය December 14, 2022.

- ^ "GINI index coefficient". CIA Factbook. 7 July 2021 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 16 July 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF) (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. සම්ප්රවේශය 30 September 2022.

- ^ a b Van Reybrouck, David (2015). Congo : the epic history of a people. New York, NY: HarperCollins. pp. Chapter 1 and 2. ISBN 9780062200129.

- ^ Coghlan, Benjamin; et al. (2007). Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An ongoing crisis: Full 26-page report (PDF) (Report). p. 26. 8 September 2013 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත (PDF). සම්ප්රවේශය 21 March 2013.

- ^ Robinson, Simon (28 May 2006). "The deadliest war in the world". Time. 11 September 2013 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b Bavier, Joe (22 January 2008). "Congo War driven crisis kills 45,000 a month". Reuters. 14 April 2011 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 2 May 2010.

- ^ "Measuring Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo" (PDF). International Rescue Committee. 2007. 11 August 2011 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත (PDF). සම්ප්රවේශය 2 September 2011.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of Congo in Crisis | Human Rights Watch". 13 May 2021 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 May 2021.

- ^ Mwanamilongo, Saleh; Anna, Cara (24 January 2019). "Congo's surprise new leader in 1st peaceful power transfer". Associated Press. 18 May 2021 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 29 May 2021.

- ^ a b BBC. (9 October 2013). "DR Congo: Cursed by its natural wealth". BBC News website සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 31 මැයි 2018 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Foreword by UNDP Administrator", Arab Human Development Report 2022, Arab Human Development Report (United Nations): pp. ii–iii, 2022-06-29, , , http://dx.doi.org/10.18356/9789210019293c001, ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 2023-01-16

- ^ Samir Tounsi (6 June 2018). "DR Congo crisis stirs concerns in central Africa". AFP. 13 June 2018 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 6 June 2018.

- ^ Robyn Dixon (12 April 2018). "Violence is roiling the Democratic Republic of Congo. Some say it's a strategy to keep the president in power". Los Angeles Times. 8 June 2018 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 June 2018.

- ^ Bobineau, Julien; Gieg, Philipp (2016). The Democratic Republic of the Congo. La République Démocratique du Congo (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). LIT Verlag Münster. p. 32. ISBN 978-3-643-13473-8.