ගැහැනිය

මෙම ලිපිය පරිවර්තනය කළ යුතුය කරුණාකර මෙම ලිපිය සිංහල භාෂාවට පරිවර්තනය කිරීමෙන් දායකවන්න. |

ගැහැනිය යනු මනව වර්ගයාට අයත් ස්ත්රී ලිංගික ජීවියාය.ගැහැනිය යනුවෙන් සමාන්යයෙන් වැඩුනු හෙවත් ලිංගික පරිණතියට පත් ස්ත්රිය ලෙස හඳුන්වයි.කුඩා වියේදී ගැහැණු ළමයා ලෙස හදුන්වයි.එනම් ගැහැනිය යනු ගැහැනු මානවයාය.මිනිස් දරුවකුට උපත ලබාදිය හැක්කේ ගැහැනියට පමණය.මිනිසා ක්ෂීරපායි කාණ්ඩයට අයත් බැවින් මවු කුසින් බිහිවන මිනිස් ළදරුවා තම මවගෙන් කිරි උරාබීම සිදුකරයි.දරුවන් හදාවඩා ගැනීමේදී වැඩි මෙහෙයක් ගැහැනිය අතින් සිදුවේ.

නිරුක්තිය

[සංස්කරණය]ඉංග්රීසි බසින් ගැහැනිය හැදින්වීමට භාවිතවන "woman" යන වචනය wīfmann යන වචනයෙන් බිඳී අවකි. [1] wīmmann යන වදන wumman , සෙද අවසානයේ woman වෙනස්වී ඇත.[2] පැරණි ඉංග්රීසි භාෂාවේ wīfmann යන වදනෙහි තේරුමද ගැහැණිය යන්නයි.

තවත් අදහසක් නම් "woman" යන වචනය "womb".යන වචනයෙන් බිඳී ආවක් බවයි.පැරණි ඉංග්රීසි භාෂාවේ wambe යන වචනයේ අරුත උදරය යන්නයි.[3][4]

සිංහල බසින් ගැහැනිය යන වදනට සමාන පද ලෙස ස්ත්රිය,ලඳ,ලලනාව,ලතා,මාගම,මහිලාව,වාමී,වනිතාව,නාරී,බවලතී යන පද යෙදේ.

ජීව විද්යාත්මක සංකේතය

[සංස්කරණය]ග්රීක දේව විශ්වාසයන්ට අනුව ස්ත්රීත්වයට අධිපත් දේවතාවිය වන වීනස් දෙවඟනගේ සංකේතය ගැහැනිය හැදින්වීමට යොදාගනී.[5]

ජීව විද්යාව

[සංස්කරණය]

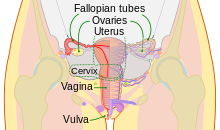

ජීව විද්යාත්මකව ගැහැනියට ස්ත්රී ප්රජනන පද්ධතියට අයත් අවයව පිහිටයි.කලලයක් දරා සිටීම හා එය පොෂණය කර මෙලොවට බිහිවීම හා එසේ බිහිවූ දරුවාට කිරි දී පොෂණය කිරීම හා සමාජයට අනුගත කිරීම යන කාර්ය රැසක් ගැහැනිය විසින් සිදුකරයි.ගැහැනු දරුවකු හා පිරිමි දරුවකු උපතේදී ලිංගික අවයව පරික්ෂා කිරීමෙන් මිස වෙනත් බාහිර ලක්ෂණ අනුව ලිංගිකත්වය හඳුනාගත නොහැකිය.එහෙත් ඇය ක්රමයෙන් වැඩිවියට පත්වන විට ක්රමයෙන් ද්වී ලිංගික ලක්ෂණ ඇතිවේ.ද්වී ලිංගික ලක්ෂණ මතුවීම ආසන්න වශයෙන් වයස අවුරුදු 10-13 අතර කාලය තුල සිදුවේ.මුලින්ම ඇයට ප්රථම ඔපස්වීම මෙම කාලය තුල සිදුවන අතර ඒ සමගම ද්වී ලිංගික ලක්ෂණ ඇතිවීම සිදුවේ.එවන් ද්වී ලිංගික ලක්ෂණ ලෙස කලවා අත් ගොබ මහත්වීම,පියයුරු වර්ධනයවීම,උකුල පළල් වීම, ලිංගේන්ද්රිය විශාලවීම,කිහිලි හා ලිංගේන්ද්රිය අවට රෝම වැවීම,යෝනි ස්රාව ඇතිවීම දැක්විය හැක.මෙසේ ද්වී ලිංගික ලක්ෂණ ඇතිවීම මගින් ඇය නව ජනිතයන්ට ජීවය ලබාදීමට සුදුසු තත්වයේ පසුවන බව පෙන්වයි.මෙම ද්වී ලිංගික ලක්ෂණ ඊස්ට්රජන් හෝමොනයේ ක්රියාකාරීත්වය නිසා ඇතිවේ.අර්ථවය ආරම්භ වීමත් සමග සංසේචනය නොවූ ඩිම්බ පිටවීම මාසිකව සිදුවේ.ලිංගිකව පරිණතවූ ගැහැනියක් හා පුරුෂයෙකු අතර ඇතිවන ලිංගික සංසර්ගයේදී පුරුෂයාගේ ශිශ්නයෙන් පිටවන ශුක්රාණු යෝනි මාර්ගය හරහා පැලෝපීය නාලවෙත ගමන්කර ඩිම්බයක් හා සංසේචනයවී ගර්භාෂයේ තැන්පත්වී ක්රමයෙන් වර්ධනයවී නව ජනිතයෙකු ලොවට බිහිවේ.

ස්ත්රීන්ගේ බාහිර ලිංගික අවයවය ලෙස යෝනිය හඳුන්වයි.යොනි තොල් භගමණිය හා යෝනි විවරය ලිංගික සංසර්ගයේදී වැදගත්වේ.යෝනිය පුරුෂ ලිංගය ඇතුලු කිරීමේදී මෙන්ම දරු ප්රසූතියකදී ප්රසාරණය වීමේ හැකියාව පවතී. මිනිසා ක්ඹීරපායි සතකු බැවින් දරු ප්රසූතියෙන් පසු ළදරුවා විසින් කිරි උරාබීම සිදුකරයි.අනෙකුත් ක්ෂීරපායි සතුන්ගේ මෙන් දරු උපතින් පසු පියයුරු විශාල වීමක් ගැහැනිය තුලද දැකිය හැක.මෙම පියයුරු විශාලව වැඩීම ලිංගික දැරියක් මල්වරවීමෙන් ඇරඹේ.දරු ප්රසූතියෙන් පසු ඉතා හොදින් පියයුරු වැඩේ.මෙමගින් අලුත උපන් දරුවාට කිරි උරාබීම පහසු කරවයි.මීට අමතරව ලිංගික තෘප්තිය ලබාගත හැකි ස්ථානයක් ලෙසද පියයුරු ඉතා වැදගත්වේ.ස්ත්රී පුරුෂයන් වෙන් කොට හඳුනා ගැනීමටද පියයුරු වැදගත්වේ.පුරුෂයන්හටද නිසිලෙස නොවැඩුනු අසම්පූර්ණ පියයුරු දැකිය හැකිය.එහෙත් එම පියයුරු මගින් කිසි ලෙසකින් කිරි නිපදවීම සිදු නොවේ.

පුද්ගලයෙකුගේ ස්ත්රී පුරුෂ භාවය තීරනය වන්නේ ඩිම්බයක් හා ශුක්රාණුවත් අතර ඇතිවන සංසේචනයේදීමය.මිනිස් ශුක්රාණුවක හා ඩිම්බයක වර්ණ දේහ 23 බැගින් ඇත.මෙම වර්ණ දේහ සංසේචනයෙන් පසු 48ක් බවට පත්වේ.මවු පාර්ශවයෙන් ලැබෙන වර්ණ දේහයක අඩංගු වන්නේ X වර්ගයට අයත් වර්ණ දේහ පමණය.පිය පාර්ශවයෙන් ලැබෙන ශුක්රාණුවක X හෝ Y වර්ගයට අයත් වර්ණ දේහ පිහිටා තිබිය හැක.ඒ අනුව X වර්ණ දේහ දෙකක් එක්වීමෙන් ගැහැණු දරුවකු බිහිවේ.වර්ණ දේහ යුගල XY ලෙස එක්වුව හොත් පිරිමි දරුවකු බිහිවේ.ඒ අනුව උපත ලබන දරුවා කුමන ලිංගයට අයත් වන්නේද යන්න තීරනය වන්නේ පිය පාර්ශවයෙන් ලැබෙන වර්ණ දේහය මතයි.

මවගෙන් හා පියාගෙන් ලැබෙන වර්ණ දේහවල අඩංගු ජාන තුල ඇති DNA අනු මිගින් නව ජනිතයාගේ ස්වරූපය තීරනය වෙයි.DNA මගින් පුද්ගල ස්වභාවය තීරනය කිරීමේදී පිය පාර්ෂවයට වඩා වැඩි වටිනාකමක්මවු පාර්ශවයට ලැබේ.එයට හේතුව නම් මවු පාර්ශවයෙන් ලැබෙන මක්රොෙකාන්ඩීය DNA අනු වෙනස් නොවී පැවතීමයි.ඒ අනුව යම් මානව වර්ගයක පූර්වජකයන් කෙසේද යන්න තීරනය කිරීමට මානව විද්යාඥයන් විසින් මයික්රොෙකාන්ඩීය DNA පරීක්ෂණය යොදාගනී.

ආයු අපේක්ෂාව අනුව පිරිමියාට වැඩි ආයු කාලයක් ස්ත්රිය ගතකරයි.[6] genetics (redundant and varied genes present on sex chromosomes in women); sociology (such as the fact that women are not expected in most modern nations to perform military service); health-impacting choices (such as suicide or the use of cigarettes, and alcohol); the presence of the female hormone estrogen, which has a cardioprotective effect in premenopausal women; and the effect of high levels of androgens in men. Out of the total human population in 2015, there were 101.8 men for every 100 women.[7]

Girls' bodies undergo gradual changes during puberty, analogous to but distinct from those experienced by boys. Puberty is the process of physical changes by which a child's body matures into an adult body capable of sexual reproduction to enable fertilisation. It is initiated by hormonal signals from the brain to the gonads-either the ovaries or the testes. In response to the signals, the gonads produce hormones that stimulate libido and the growth, function, and transformation of the brain, bones, muscle, blood, skin, hair, breasts, and sexual organs. Physical growth—height and weight—accelerates in the first half of puberty and is completed when the child has developed an adult body. Until the maturation of their reproductive capabilities, the pre-pubertal, physical differences between boys and girls are the genitalia, the penis and the vagina. Puberty is a process that usually takes place between the ages 10–16, but these ages differ from girl to girl. The major landmark of girls' puberty is menarche, the onset of menstruation, which occurs on average between ages 12–13.[8][9][10][11]

Most girls go through menarche and are then able to become pregnant and bear children.[12] This generally requires internal fertilization of her eggs with the sperm of a man through sexual intercourse, though artificial insemination or the surgical implantation of an existing embryo is also possible (see reproductive technology). The study of female reproduction and reproductive organs is called gynaecology.[13]

සෞඛ්ය

[සංස්කරණය]

Women's health refers to health issues specific to human female anatomy. There are some diseases that primarily affect women, such as lupus. Also, there are some gender-related illnesses that are found more frequently or exclusively in women, e.g., breast cancer, cervical cancer, or ovarian cancer. Women and men may have different symptoms of an illness and may also respond to medical treatment differently. This area of medical research is studied by gender-based medicine.[14]

The issue of women's health has been taken up by many feminists, especially where reproductive health is concerned. Women's health is positioned within a wider body of knowledge cited by, amongst others, the World Health Organisation, which places importance on gender as a social determinant of health.[15]

Maternal mortality or maternal death is defined by WHO as "the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes."[16] About 99% of maternal deaths occur in developing countries. More than half of them occur in sub-Saharan Africa and almost one third in South Asia. The main causes of maternal mortality are severe bleeding (mostly bleeding after childbirth), infections (usually after childbirth), pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, unsafe abortion, and pregnancy complications from malaria and HIV/AIDS.[17] Most European countries, Australia, as well as Japan and Singapore are very safe in regard to childbirth, while Sub-Saharan countries are the most dangerous.[18]

ප්රජනන අයිතිය හා නිදහස

[සංස්කරණය]

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics has stated that:[19]

- (...) the human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. Equal relationships between women and men in matters of sexual relations and reproduction, including full respect for the integrity of the person, require mutual respect, consent and shared responsibility for sexual behavior and its consequences.

Violations of reproductive rights include forced pregnancy, forced sterilization and forced abortion.

Forced sterilization was practiced during the first half of the 20th century by many Western countries. Forced sterilization and forced abortion are reported to be currently practiced in countries such as Uzbekistan and China.[20][21][22][23][24][25]

The lack of adequate laws on sexual violence combined with the lack of access to contraception and/or abortion are a cause of enforced pregnancy (see pregnancy from rape).[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

සංස්කෘතිය

[සංස්කරණය]

In many prehistoric cultures, women assumed a particular cultural role. In hunter-gatherer societies, women were generally the gatherers of plant foods, small animal foods and fish, while men hunted meat from large animals.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

In more recent history, gender roles have changed greatly. Originally, starting at a young age, aspirations occupationally are typically veered towards specific directions according to gender.[26] Traditionally, middle class women were involved in domestic tasks emphasizing child care. For poorer women, especially working class women, although this often remained an ideal,[specify] economic necessity compelled them to seek employment outside the home. Many of the occupations that were available to them were lower in pay than those available to men.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

As changes in the labor market for women came about, availability of employment changed from only "dirty", long hour factory jobs to "cleaner", more respectable office jobs where more education was demanded, women's participation in the U.S. labor force rose from 6% in 1900 to 23% in 1923. These shifts in the labor force led to changes in the attitudes of women at work, allowing for the revolution which resulted in women becoming career and education oriented.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

In the 1970s, many female academics, including scientists, avoided having children. However, throughout the 1980s, institutions tried to equalize conditions for men and women in the workplace. However, the inequalities at home stumped women's opportunities to succeed as far as men. Professional women are still responsible for domestic labor and child care. As people would say, they have a "double burden" which does not allow them the time and energy to succeed in their careers. Furthermore, though there has been an increase in the endorsement of egalitarian gender roles in the home by both women and men, a recent research study showed that women focused on issues of morality, fairness, and well-being, while men focused on social conventions.[27] Until the early 20th century, U.S. women's colleges required their women faculty members to remain single, on the grounds that a woman could not carry on two full-time professions at once. According to Schiebinger, "Being a scientist and a wife and a mother is a burden in society that expects women more often than men to put family ahead of career." (pg. 93).[28]

Movements advocate equality of opportunity for both sexes and equal rights irrespective of gender. Through a combination of economic changes and the efforts of the feminist movement,[specify] in recent decades women in many societies now have access to careers beyond the traditional homemaker.

Although a greater number of women are seeking higher education, salaries are often less than those of men. CBS News claimed in 2005 that in the United States women who are ages 30 to 44 and hold a university degree make 62 percent of what similarly qualified men do, a lower rate than in all but three of the 19 countries for which numbers are available. Some Western nations with greater inequity in pay are Germany, New Zealand and Switzerland.[29]

කාන්තාවන්ට එරෙහි ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය

[සංස්කරණය]

The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women defines "violence against women" as:[30]

any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

and identifies three forms of such violence: that which occurs in the family, that which occurs within the general community, and that which is perpetrated or condoned by the State. It also states that "violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women".[31]

Violence against women remains a widespread problem, fueled, especially outside the West, by patriarchal social values, lack of adequate laws, and lack of enforcement of existing laws. Social norms that exist in many parts of the world hinder progress towards protecting women from violence. For example, according to surveys by UNICEF, the percentage of women aged 15–49 who think that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife under certain circumstances is as high as 90% in Afghanistan and Jordan, 87% in Mali, 86% in Guinea and Timor-Leste, 81% in Laos, and 80% in the Central African Republic.[32] A 2010 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found that stoning as a punishment for adultery was supported by 82% of respondents in Egypt and Pakistan, 70% in Jordan, 56% Nigeria, and 42% in Indonesia.[33]

Specific forms of violence that affect women include female genital mutilation, sex trafficking, forced prostitution, forced marriage, rape, sexual harassment, honor killings, acid throwing, and dowry related violence. Governments can be complicit in violence against women, for instance through practices such as stoning (as punishment for adultery).

There have also been many forms of violence against women which have been prevalent historically, notably the burning of witches, the sacrifice of widows (such as sati) and foot binding. The prosecution of women accused of witchcraft has a long tradition, for example witch trials in the early modern period (between the 15th and 18th centuries) were common in Europe and in the European colonies in North America. Today, there remain regions of the world (such as parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, rural North India, and Papua New Guinea) where belief in witchcraft is held by many people, and women accused of being witches are subjected to serious violence.[34][35][36] In addition, there are also countries which have criminal legislation against the practice of witchcraft. In Saudi Arabia, witchcraft remains a crime punishable by death, and in 2011 the country beheaded a woman for 'witchcraft and sorcery'.[37][38]

It is also the case that certain forms of violence against women have been recognized as criminal offenses only during recent decades, and are not universally prohibited, in that many countries continue to allow them. This is especially the case with marital rape.[39][40] In the Western World, there has been a trend towards ensuring gender equality within marriage and prosecuting domestic violence, but in many parts of the world women still lose significant legal rights when entering a marriage.[41]

Sexual violence against women greatly increases during times of war and armed conflict, during military occupation, or ethnic conflicts; most often in the form of war rape and sexual slavery. Contemporary examples of sexual violence during war include rape during the Bangladesh Liberation War, rape in the Bosnian War, rape during the Rwandan Genocide, and rape during Second Congo War. In Colombia, the armed conflict has also resulted in increased sexual violence against women.[42]

Laws and policies on violence against women vary by jurisdiction. In the European Union, sexual harassment and human trafficking are subject to directives.[43][44]

විලාසිතා

[සංස්කරණය]Women in different parts of the world dress in different ways, with their choices of clothing being influenced by local culture, religious tenets traditions, social norms, and fashion trends, amongst other factors. Different societies have different ideas about modesty. However, in many jurisdictions, women's choices in regard to dress are not always free, with laws limiting what they may or may not wear. This is especially the case in regard to Islamic dress. While certain jurisdictions legally mandate such clothing (the wearing of the headscarf), other countries forbid or restrict the wearing of certain hijab attire (such as burqa/covering the face) in public places (one such country is France - see French ban on face covering). These laws are highly controversial.[45]

පවුල් ජීවිතය

[සංස්කරණය]

| 7–8 Children 6–7 Children 5–6 Children 4–5 Children | 3–4 Children 2–3 Children 1–2 Children 0–1 Children |

The total fertility rate (TFR) - the average number of children born to a woman over her lifetime — differs significantly between different regions of the world. In 2016, the highest estimated TFR was in Niger (6.62 children born per woman) and the lowest in Singapore (0.82 children/woman).[47] While most Sub-Saharan African countries have a high TFR, which creates problems due to lack of resources and contributes to overpopulation, most Western countries currently experience a sub replacement fertility rate which may lead to population ageing and population decline.

In many parts of the world, there has been a change in family structure over the past few decades. For instance, in the West, there has been a trend of moving away from living arrangements that include the extended family to those which only consist of the nuclear family. There has also been a trend to move from marital fertility to non-marital fertility. Children born outside marriage may be born to cohabiting couples or to single women. While births outside marriage are common and fully accepted in some parts of the world, in other places they are highly stigmatized, with unmarried mothers facing ostracism, including violence from family members, and in extreme cases even honor killings.[48][49] In addition, sex outside marriage remains illegal in many countries (such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan,[50] Afghanistan,[51][52] Iran, Kuwait,[53] Maldives,[54] Morocco,[55] Oman,[56] Mauritania,[57] United Arab Emirates,[58][59] Sudan,[60] and Yemen[61]).

The social role of the mother differs between cultures. In many parts of the world, women with dependent children are expected to stay at home and dedicate all their energy to child raising, while in other places mothers most often return to paid work (see working mother and stay-at-home mother).

ආගම

[සංස්කරණය]Particular religious doctrines have specific stipulations relating to gender roles, social and private interaction between the sexes, appropriate dressing attire for women, and various other issues affecting women and their position in society. In many countries, these religious teachings influence the criminal law, or the family law of those jurisdictions (see Sharia law, for example). The relation between religion, law and gender equality has been discussed by international organizations.[62]

Education

[සංස්කරණය]Female education includes areas of gender equality and access to education, and its connection to the alleviation of poverty. Also involved are the issues of single-sex education and religious education in that the division of education along gender lines as well as religious teachings on education have been traditionally dominant and are still highly relevant in contemporary discussions of educating females as a global consideration.

While the feminist movement has certainly promoted the importance of the issues attached to female education the discussion is wide-ranging and by no means narrowly defined. It may include, for example, HIV/AIDS education.[1] Universal education, meaning state-provided primary and secondary education independent of gender is not yet a global norm, even if it is assumed in most developed countries. In some Western countries, women have surpassed men at many levels of education. For example, in the United States in 2005/2006, women earned 62% of associate degrees, 58% of bachelor's degrees, 60% of master's degrees, and 50% of doctorates.[2]

සාක්ෂරතාව

[සංස්කරණය]World literacy is lower for females than for males. The CIA World Factbook presents an estimate from 2010 which shows that 80% of women are literate, compared to 88.6% of men (aged 15 and over). Literacy rates are lowest in South and West Asia, and in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa.[63]

The educational gender gap in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries has been reduced over the last 30 years. Younger women today are far more likely to have completed a tertiary qualification: in 19 of the 30 OECD countries, more than twice as many women aged 25 to 34 have completed tertiary education than have women aged 55 to 64. In 21 of 27 OECD countries with comparable data, the number of women graduating from university-level programmes is equal to or exceeds that of men. 15-year-old girls tend to show much higher expectations for their careers than boys of the same age.[64] While women account for more than half of university graduates in several OECD countries, they receive only 30% of tertiary degrees granted in science and engineering fields, and women account for only 25% to 35% of researchers in most OECD countries.[65]

There is a common misconception that women have still not advanced in achieving academic degrees. According to Margaret Rossiter, a historian of science, women now earn 54 percent of all bachelor's degrees in the United States. However, although there are more women holding bachelor's degrees than men, as the level of education increases, the more men tend to fit the statistics[පැහැදීම ඇවැසිය] instead of women. At the graduate level, women fill 40 percent of the doctorate degrees (31 percent of them being in engineering).[66]

While to this day women are studying at prestigious universities at the same rate as men,[පැහැදීම ඇවැසිය] they are not being given the same chance to join faculty. Sociologist Harriet Zuckerman has observed that the more prestigious an institute is, the more difficult and time-consuming it will be for women to obtain a faculty position there. In 1989, Harvard University tenured its first woman in chemistry, Cynthia Friend, and in 1992 its first woman in physics, Melissa Franklin. She also observed that women were more likely to hold their first professional positions as instructors and lecturers while men are more likely to work first in tenure positions. According to Smith and Tang, as of 1989, 65 percent of men and only 40 percent of women held tenured positions and only 29 percent of all scientists and engineers employed as assistant professors in four-year colleges and universities were women.[67]

රැකියා

[සංස්කරණය]In 1992, women earned 9 percent of the PhDs awarded in engineering, but only one percent of those women became professors.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත] In 1995, 11 percent of professors in science and engineering were women. In relation, only 311 deans of engineering schools were women, which is less than 1 percent of the total. Even in psychology, a degree in which women earn the majority of PhDs, they hold a significant amount of fewer tenured positions, roughly 19 percent in 1994.[68]

කාන්තා දේශපාලනය

[සංස්කරණය]

Women are underrepresented in government in most countries. In October 2013, the global average of women in national assemblies was 22%.[70] Suffrage is the civil right to vote. Women's suffrage in the United States was achieved gradually, first at state and local levels, starting in the late 19th century and early 20th century, and in 1920 women in the US received universal suffrage, with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Some Western countries were slow to allow women to vote; notably Switzerland, where women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971, and in the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden women were granted the right to vote on local issues only in 1991, when the canton was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland;[71][72] and Liechtenstein, in 1984, through a women's suffrage referendum.

කලාව හා සාහිත්ය

[සංස්කරණය]

Women have, throughout history, made contributions to science, literature and art. One area where women have been permitted most access historically was that of obstetrics and gynecology (prior to the 18th century, caring for pregnant women in Europe was undertaken by women; from the mid 18th century onwards medical monitoring of pregnant women started to require rigorous formal education, to which women did not generally have access, therefore the practice was largely transferred to men).[73][74]

Writing was generally also considered acceptable for upper class women, although achieving success as a female writer in a male dominated world could be very difficult; as a result several women writers adopted a male pen name (e.g. George Sand, George Eliot).[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

Women have been composers, songwriters, instrumental performers, singers, conductors, music scholars, music educators, music critics/music journalists and other musical professions. There are music movements, events and genres related to women, women's issues and feminism. In the 2010s, while women comprise a significant proportion of popular music and classical music singers, and a significant proportion of songwriters (many of them being singer-songwriters), there are few women record producers, rock critics and rock instrumentalists. Although there have been a huge number of women composers in classical music, from the Medieval period to the present day, women composers are significantly underrepresented in the commonly performed classical music repertoire, music history textbooks and music encyclopedias; for example, in the Concise Oxford History of Music, Clara Schumann is one of the only female composers who is mentioned.

Women comprise a significant proportion of instrumental soloists in classical music and the percentage of women in orchestras is increasing. A 2015 article on concerto soloists in major Canadian orchestras, however, indicated that 84% of the soloists with the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal were men. In 2012, women still made up just 6% of the top-ranked Vienna Philharmonic orchestra. Women are less common as instrumental players in popular music genres such as rock and heavy metal, although there have been a number of notable female instrumentalists and all-female bands. Women are particularly underrepresented in extreme metal genres.[75] Women are also underrepresented in orchestral conducting, music criticism/music journalism, music producing, and sound engineering. While women were discouraged from composing in the 19th century, and there are few women musicologists, women became involved in music education "... to such a degree that women dominated [this field] during the later half of the 19th century and well into the 20th century."[76]

According to Jessica Duchen, a music writer for London's The Independent, women musicians in classical music are "... too often judged for their appearances, rather than their talent" and they face pressure "... to look sexy onstage and in photos."[77] Duchen states that while "[t]here are women musicians who refuse to play on their looks, ... the ones who do tend to be more materially successful."

According to the UK's Radio 3 editor, Edwina Wolstencroft, the classical music industry has long been open to having women in performance or entertainment roles, but women are much less likely to have positions of authority, such as being the leader of an orchestra.[78] In popular music, while there are many women singers recording songs, there are very few women behind the audio console acting as music producers, the individuals who direct and manage the recording process.[79]

'== මේවාත් බලන්න ==

- Se x ssgent

- Lists of wom

esexn Medical:

- Feminine psychology

- Gender differences

Dynamics:

- Femininity

- Feminization (sociology)

- Matriarchy

- Misogyny

- Mitochondrial Eve

- Sexism

- Women as theological figures

- Women in science

Political:

- Gender studies

- Womyn

- List of female explorers and travelers

- Women in space

References

[සංස්කරණය]- ^ "wīfmann": Bosworth & Toller, Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (Oxford, 1898-1921) p. 1219. The spelling "wifman" also occurs: C. T. Onions, Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (Oxford, 1966) p. 1011

- ^ Webster's New World Dictionary, Second College Edition, entry for "woman".

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Jose A. Fadul. Encyclopedia of Theory & Practice in Psychotherapy & Counseling p. 337

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ (Tanner, 1990).

- ^ Anderson SE, Dallal GE, Must A (April 2003). "Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: results from two nationally representative surveys of US girls studied 25 years apart". Pediatrics. 111 (4 Pt 1): 844–50. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.844. PMID 12671122.

- ^ "Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth". BMC Public Health. 10. BMC Public Health: 736. 2010. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-736. PMC 3001737. PMID 21110899.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|DOI=and|doi=specified (help); More than one of|PMC=and|pmc=specified (help); More than one of|PMID=and|pmid=specified (help) - ^ Hamilton-Fairley, Diana. "Obstetrics and Gynaecology" (PDF) (Second ed.). Blackwell Publishing. 2013-12-09 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2018-01-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Menarche and menstruation are absent in many of the intersex and transgender conditions mentioned above and also in primary amenorrhea.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ http://www.who.int/social_determinants

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ "Uzbekistan's policy of secretly sterilising women". BBC News. 12 April 2012.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ "China forced abortion photo sparks outrage". BBC News. 14 June 2012.

- ^ සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත, http://www.hrnk.org/uploads/pdfs/HRNK_HiddenGulag2_Web_5-18.pdf, ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 2018-01-11

- ^ Sharpe, S. (1976). Just like a Girl. London: Penguin.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Gere, J., & Helwig, C. C. (2012). Young adults' attitudes and reasoning about gender oles in the family context. "Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36", 301-313. doi: 10.1177/0361684312444272

- ^ Schiebinger, Londa (1999). Has Feminism Changed Science? : Science and Private Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 92–103.

- ^ "U.S. Education Slips In Rankings". CBS News. 13 September 2005.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1129&context=djcil#H2N1

- ^ http://www.mrc.ac.za/crime/witchhunts.pdf

- ^ "Woman burned alive for 'sorcery' in Papua New Guinea". BBC News. 7 February 2013.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ "Saudi woman beheaded for 'witchcraft and sorcery' - CNN.com". CNN. 14 December 2011.

- ^ In 2006, the UN Secretary-General's In-depth study on all forms of violence against women found that (pg 113): "Marital rape may be prosecuted in at least 104 States. Of these, 32 have made marital rape a specific criminal offence, while the remaining 74 do not exempt marital rape from general rape provisions. Marital rape is not a prosecutable offence in at least 53 States. Four States criminalize marital rape only when the spouses are judicially separated. Four States are considering legislation that would allow marital rape to be prosecuted."[1]

- ^ In England and Wales, marital rape was made illegal in 1991. The views of Sir Matthew Hale, a 17th-century jurist, published in The History of the Pleas of the Crown (1736), stated that a husband cannot be guilty of the rape of his wife because the wife "hath given up herself in this kind to her husband, which she cannot retract"; in England and Wales this would remain law for more than 250 years, until it was abolished by the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords, in the case of R v R in 1991.

- ^ For example, in Yemen, marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[2] In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives. The criminal code states at Paragraph 41 that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right; examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom".

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) In the Democratic Republic of Congo the Family Code states that the husband is the head of the household; the wife owes her obedience to her husband; a wife has to live with her husband wherever he chooses to live; and wives must have their husbands' authorization to bring a case in court or to initiate other legal proceedings.[3] - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Directive 2002/73/EC — equal treatment of 23 September 2002 amending Council Directive 76/207/EEC on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment for men and women as regards access to employment, vocational training and promotion, and working conditions [4]

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ "Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States". CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. May 13, 2009. සම්ප්රවේශය September 24, 2011.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20130501013343/http://www.mrt-rrt.gov.au/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=91cf943a-3fa6-4fce-afec-4ab2c2a356fd

- ^ "Turkey condemns 'honour killings'". BBC News. 1 March 2004.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ "Iran". Travel.state.gov. 2013-08-01 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Fakim, Nora (9 August 2012). "BBC News – Morocco: Should pre-marital sex be legal?". BBC.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Judd, Terri (10 July 2008). "Briton faces jail for sex on Dubai beach – Middle East – World". The Independent. London.

- ^ "Sudan must rewrite rape laws to protect victims". Reuters. 28 June 2007.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Education Levels Rising in OECD Countries but Low Attainment Still Hampers Some, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Publication Date: 14 September 2004. Retrieved December 2006.

- ^ Women in Scientific Careers: Unleashing the Potential, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ISBN 92-64-02537-5, Publication Date: 20 November 2006. Retrieved December 2006.

- ^ Women (Still) Need Not Apply:The Gender and Science Reader. New York: Routledge. 2001. pp. 13–23.

- ^ A six-year Longitudinal Study of Undergraduate Women in Engineering and Science:The Gender and Science Reader. New York: Routledge. 2001. pp. 24–37.

- ^ Schiebinger, Londa (1999). Has feminism changed science ?: Meters of Equity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^

{{cite web}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ Gelis, Jacues. History of Childbirth. Boston: Northern University Press, 1991: 96-98

- ^ Bynum, W.F., & Porter, Roy, eds. Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine. London and New York: Routledge, 1993: 1051-1052.

- ^ Julian Schaap and Pauwke Berkers. "Grunting Alone? Online Gender Inequality in Extreme Metal Music" in Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music. Vol.4, no.1 (2014) p. 103

- ^ "Women Composers In American Popular Song, Page 1". Parlorsongs.com. 1911-03-25. සම්ප්රවේශය 2016-01-20.

- ^ "CBC Music". 2016-03-01 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ Jessica Duchen. "Why the male domination of classical music might be coming to an end | Music". The Guardian. සම්ප්රවේශය 2016-01-20.

- ^ Ncube, Rosina (September 2013). "Sounding Off: Why So Few Women In Audio?". Sound on Sound.