මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය (HPV) මිසකුගෙන් මිනිසකුට බොවියහැකි වෛරසයකි.[1] මෙම වෛරසය මානව සිරුරතුල විවිධ රෝග ලක්ෂණ ඇතිවීමට හේතුවේ. මෙම වෛරසය අසාදනය වූවිට සිරුරේ ඉන්නන් තුවාල ආදිය ඇතිවීම වැනි සංකූලතා දක්නට ලැබේ. ඇතැම් තුවාල පිළිකා දක්වා වර්ධනයවේ.ගැබ්ගෙල,යෝනිය, ශිශ්නය, උගුර, ගුදය,මුඛය ආශිත පිළිකා මේ අතර ප්රධානය.[2] මෙම පිළිකා අතරින් වැඩිම මරණ සංඛාවක් වාර්ථා වෙන්නේ ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා ආශිතවය.මෙම ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා ඇතිකරවන වෛරස වර්ග අතර HPV16 සහ PV18, ප්රමුඛය.[3][4] වෙනත් පිළිකා කෙරෙහිද මෙම වෛරසය ඍජු බලපෑමක් ඇත. HPV6 සහ HPV11 යන වෛරස් කාණ්ඩ නිසා ලිංගික පෙදෙස්වල ඉන්නන් ඇතිවේ.

මෙම මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස් පවුලට අයත් වෛරස් විශේෂ 170 පමණ පවතී. මේ අතරින් වෛරස් විශේෂ 40 පමණ ලිංගිකව සංප්රේෙෂණයවේ. බොහෝවිට මෙම වෛරසය ප්රථම ලිංගික එක්වීමේදී ආසාධනයවේ.මීට අමතරව සමලිංගික වර්යා,ලිංගික සහකරුවන් කිහිප දෙනෙක් සමග සංසර්ගයේ යෙදීම,දුම්පානය හා ප්රතිශක්තිකරණ පද්ධතියේ ඇති දුර්වලතා හේතුවෙන් ආසාධනයවේ. මෙම වෛරසය ඍජු ස්පර්ශය මගින් ද ආසාධනයවේ. ඇතැම්විට මවගෙන් දරුවාටද බොවේ. කෙසේ වෙතත් පොදු වැසිකිළි භාවිතය මෙයට ඍජුව බලපෑමක් නොකරයි. මෙම වෛරස විශේෂ කිහිපයක් පවතී. මෙම වෛරසය මිනිසාගෙන් මිනිසාට පමණක් බෝවේ.සතුන් මගින් බෝ නොවන වෛරසයකි.[5]

මෙම වෛරස් කාණ්ඩ කිහිපයක්ම පවතී.[6] මෙම වෛරස ආසාදනය වැළක්වීම සදහා විවිද ක්රම පවතී.ඒ අතර ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ එන්නත් මූලික තැනක් ගනී.විශේෂයෙන් කාන්තාවන්ට වැළදෙන ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා වැළක්වීම සදහා පාසැල් වයසේ සිටින වයස අවුරුදු නමයත් දහතුනත් අතර වයසේ ගැහැණු ළමුන්ට මෙම ප්රතිශක්තිකරණ එන්නත ලබාදෙයි.මෙම වෛරසය ආසාධනයවී දීර්ඝ කාලයකට පසුව පිළිකා තත්වය දක්වා වර්ධනයවීම සිදුවේ.ප්රතිශක්තීකරන එන්නත ලබාදීම ඉතා සාර්ථක හා ප්රථිපලදායි ක්රමයක් ලෙස පර්යේෂකයන් පෙන්වාදෙයි.සංවර්ධනය වෙමින්පවතින රටවල් රැසකම ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා නිසා මියයන ප්රමානය ඉතා ඉහල අගයක් ගනී.[7] එබැවින් බොහෝ රජ්යයන් වර්ථමානයේදී මානව පැපිලෝම වෛරසය සදහා ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ එන්නත ලබාදීමට පියවරගෙන ඇත.

ලොව පුරා ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේෂණය වන වෛරස අතරින් වැඩිම මරණ සංඛ්යාවකට හේතුවී ඇත්තේ මෙම මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසයයි.2012 වසරේදී ඇමරිකාවේ මෙම වෛරසය ආසාදනයවූ පුද්ගලයන් 528,000 අතරින් 266,000ම මියගොස් ඇත.[8] විශේෂයෙන් දියුණු වෙමින් පවතින රටවල වෛරස ආසාධනයවූවන් අතරින් මියයන ප්රමාණය 85% පමණ වෛයි.[9] මෙම වෛරසය නිසා ඇතිවන ලිංගික ඉන්නන් පිළිබද අතීතයේ සිට දැනුමක් තිබුනද මෙය වෛරසය මුල්වරට සොයාගනු ලැබූවේ 1907දීය.[10]

රෝග ලක්ෂණ

[සංස්කරණය]

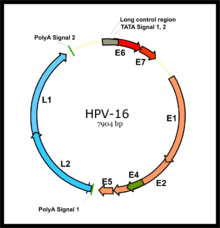

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස (HPV) කාණ්ඩ 170 පමණ සොයාගෙන ඇති අතර මේවා වර්ගීකරණයකට ලක්කර ඇත.[12]

ඇතැම් මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස (HPV) කාණ්ඩ ශරීරගත වුවද කිසිදු රෝග ලක්ෂණයක් පෙන්නුම් නොකරයි.උදාහරණ ලෙස HPV-5 වෛරස කාණ්ඩය දැක්විය හැක.HPV 1 සහ 2 කාණ්ඩ මගින් කුඩා ඉන්නන් කිප දෙනෙක් ඇතිවීම පමණක් සිදුවේ.HPV 6 සහ 11 මගින් ලිංගික අවයව තුල ඉන්නන් ඇතිවේ.HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, සහ 82 යන වෛරස කාණ්ඩ මගින් පිළිකා අවධානම ඇතිවේ.[13]

| රෝගය | මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස කාණ්ඩය |

|---|---|

| සාමාන්ය ඉන්නන් | 2, 7, 22 |

| ගල්තැලුම් | 1, 2, 4, 63 |

| පැතලි ඉන්නන් | 3, 10, 8 |

| ලිංගික ඉන්නන් | 6, 11, 42, 44 සහ වෙනත් |

| ගුද මාර්ගයේ තුවාල | 6, 16, 18, 31, 53, 58[14] |

| ලිංගික පෙදෙස් වල පිළිකා | |

| සමේ ගැටිති | වෛරස කාණ්ඩ 15 වැඩි |

| අතිප්ලාස්මීයතාව | 13, 32 |

| මුඛයේ තුවාල | 6, 7, 11, 16, 32 |

| ස්වරාලයේ පිළිකා | 16 |

| විසප්පු ගෙඩි | 60 |

| ස්වරාලයේ තුවාල | 6, 11 |

ඉන්නන්

[සංස්කරණය]

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය (HPV) සමග සුලභ ලෙස ඉන්නන් ඇතිවීම දැකිය හැකිය.[17] HPV වෛරසය ආසාදනය හේතුවෙන් සම මතුපිට ඇති සෛල වේගයෙන් වර්ධනයවීමට පටන්ගනී.මෙය ඉන්නන් ලෙස දිස්වේ.[18]

HPV වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් කුඩා දරුවන්ටද සම මතුපිට ඉන්නන් ඇතිවීම දැකිය හැකිය.කෙසේ වෙතත් මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ශරීරගතවී බොහෝ කලකට පසුව රෝග ලක්ෂණ මතුවීම සාමන්යයේන් සිදුවන්නකි.ඇතැම් විට පුද්ගලයන්ගේ ප්රතිශක්තිකරණ පද්ධතිය ශක්තිමත් නම් මෙම වෛරසය සම්පූර්ණයෙන්ම ඉවත්වීයයි.එවිට කිසිදු අවදානමක් ඇති නොවේ.ඇතැම් මානව පැපිලොමා වෛරස (HPV) කාණ්ඩ ආසාදනයවූ පුද්ගලයන්ට කිසිදු රෝග ලක්ෂණයක් පෙන්නුම්කර නැත.[19]

ඉන්නන් ප්රභේද කිහිපයක් ඇත.

- බොහෝවිට මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් ඇතිවන ඉන්නන් ප්රධාන වශයෙන් දෙඅත්,දෙපා හා වැලමිට හෝ දණහිස් අසළ ඇතිවේ.ඇතැම්විට ලිංගික අවයව අශ්රීතවද ඉන්නන් ඇතිවේ.නමුත් මෙම ඉන්නන් හා පිළිකා අතර සම්භන්ධයක් නැත.

- ඇතැම් ඉන්නන් පාදයේ හටගන්නා අතර අවිදීමේදී වේදනාවක් ඇතිවේ.

- ඇතැම් ඉන්නන් නියපොතු ඇසුරුකරගෙන වැඩේ.මෙම ඉන්නන්ට ප්රතිකාර කිරීමද අපහසුය.[20]

- අත් මුහුණ නළල යන ස්ථාන වලද මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් ඉන්නන් ඇතිවේ.මේවාද පිළිකා කෙරෙහි සම්භන්ධයක් නැත.[21]

මෙම ඉන්නන් ස්පර්ශය මගින් පුද්ගලයෙකුගෙන් තවත් පුද්ගලයෙකුට වෛරසය පැතිරේ.

ලිංගික ඉන්නන්

[සංස්කරණය]HPV වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් ලිංගික අවයව ආශ්රිත ඉන්නන් ඇතිවීම බොහෝ දුරට අසන්නට ලැබේ.විශේෂයෙන් ජනනේද්රිය හා ගුදය ආශ්රිතව ඉන්නන් හටගනී.සමලිංගික චර්යා හා ගුද ලිංගික චර්යා මගින් මෙය ඉක්මනින් ව්යාප්තවේ.

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය මගින් ඇතිවන ලිංගික ඉන්නන් හා සිරුරෙ අනෙකුත් ප්රදේශවල ඇතිවන ඉන්නන් අතර වෙනසක් පවතී.ලිංගික ඉන්නන් ඇතිවීම කෙරෙහි HPV 6 හා HPV 11 යන වෛරස කාණ්ඩ ප්රධානය.[22] HPV වෛරස කාණ්ඩ 40 පමණ ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේෂණය වෙයි.

HPV හෙවත් මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ආසාදනය වීම හා රෝග ලක්ෂණ පෙන්වීම පුද්ගලයා ගෙන් පුද්ගලයාට වෙනස්වේ.ඇතමුන්ගේ ප්රතිශක්තිකරන පද්ධතිය ශක්තිමත් නිසා වෛරසය ශරීරගත වුවද එය මැඩපැවැත්වීමට ප්රතිශක්තිකරණ පද්ධතියට හැකිවේ.ඇතැම් අයට මෙය ශරීරගතවී පැවතුනද කිසිදු රෝග ලක්ෂණයක් පෙන්නුම් නොකරන අතර කෙසේ වෙතත් තවදුරටත් ඔහු රෝග වාහකයෙකු ලෙස ක්රියාකරයි.එවන් රෝග වාහකයෙකු සමග ඇතිකරගන්නා ලිංගික සංසර්ගයක් මගින් නිරෝගී පුද්ගලයෙකුය බෝවේ.ඇතැම්විට රෝග ලක්ෂණ පෙන්නුම් කරන පුද්ගලයෙකු හා ලිංගිකව එක් වුවද අනෙකාගේ ස්වාභාවික ප්රතිශක්තිකරණ පද්ධතිය ශක්තිමත් නම් කිසිදු රෝග ලක්ෂණයක් පෙන්නුම් නොකරයි. HPV වෛරසය ලිංගිකව පැතිරීමේදී සමලිංගික ඇසුර මගින් බෝවීමේ ප්රවනතාව ඉතා ඉහළ අවධානමක් ඇති අතර විරුද්ධ ලිංගිකයන් කිහිපදෙනෙක් සමග ඇසුර මගින් පැතිරීම ඊට සාපේක්ෂව අඩුය.එක් අයකු සමග පමණක් ලිංගිකව ඇසුරු සිදුකල අය අතර පවා HPV වෛරසය ආසාදනයවූවන් දක්නට ලැබේ.එයට හේතුව HPV වෛරසය ශරීරගතවීමට ලිංගික ඇසුර පමනක් නොව වෙනත් සාධකත් බලපාන නිසාය.ලිංගික ඉන්නන් සහිත පුද්ලයන්ගේ ඉන්නන් සමෙහි ස්පර්ෂ වීමෙන්ද බෝවේ.එම ස්පර්ශයන් ලිංගික හෝ ලිංගික නොවන ස්පර්ශයන් වියහැක.

පිළිකා

[සංස්කරණය]

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස කාණ්ඩ දොළහක් පමණ පිළිකා ඇතිකිරීමේ වැඩි අවධානමක පවතී.මෙම වෛරස යෝනිය,ශිශ්නය,ගැබ්ගෙල,ගුදය වැනි ස්ථානවල පිළිකා ඇති කිරීමට හේතුවේ.[2][23] HPV 16 මෙන්ම HIV 18 වෛරසද ගැබ්ගෙල හා ගුද පිළිකා ඇතිවීමේ ඇතිවීමේ අවධානම වැඩි කරයි.

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් ඇතිවන පිළිකා රෝග ලොවපුරාම බහුලව වාර්ථාවේ.සංවර්ධිත හා සංවර්ධනය වෙමින් පවතින රටවලද මෙය දක්නට ලැබේ.කෙසේ වෙතත් සංවර්ධිත රටවලට වඩා සංවර්ධනය වෙමින් පවතින රටවල රෝගීන් ප්රමාණය හා ඒ හේතුවෙන් මියයන ප්රමාණය වැඩිය.සංවර්ධිත රටවල පවතින ඉහළ සෞඛ්ය පහසුකම් නිසා මෙම පිළිකා රෝග ඉතා පහසුවෙන් හඳුනාගෙන ප්රතිකාර කරන බැවින් රෝගීන් ඉක්මනින් සුවය ලැබීම සිදුවේ.එබැවින් මරණ සංඛාවද සංවර්ධිත රටවල අවමය.

පහත දැක්වෙන්නේ ඇමරිකාවේ වාර්ථාවූ මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස ආසාදනය හා පිළිකා පිළිබදවය.මෙම වගුවෙන් දැක්වෙන පරිධී පිළිකා රෝග රැසකටම මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස ආසාදනය හේතුවී ඇතැයි අනුමාන කළහැක.

| පිළිකා ප්රදේශ | වාර්ෂික රෝගී සංඛාව | HPV ආසාදිත බව තහවුරුවූ | HPV 16/18 ආසාදිත බව තහවුරුවූ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ගැබ්ගෙල | 11,967 | 11,500 | 9,100 |

| යෝනිය මුඛය | 3,136 | 1,600 | 1,400 |

| යෝනිය | 729 | 500 | 400 |

| ශිශ්නය | 1,046 | 400 | 300 |

| ගුදය (ස්ත්රී) | 3,089 | 2,900 | 2,700 |

| ගුදය (පුරුෂ) | 1,678 | 1,600 | 1,500 |

| ග්රසනිකාව (ස්ත්රී) | 2,370 | 1,500 | 1,400 |

| ග්රසනිකාව (පුරුෂ) | 9,356 | 5,900 | 5,600 |

| සම්පූර්ණl (ස්ත්රී) | 21,291 | 18,000 | 15,000 |

| සම්පූර්ණl (පුරුෂ) | 12,080 | 7,900 | 7,600 |

බොහෝ පුද්ගලයන්ගේ ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ පද්ධතිය ඇතැම් වෛරස කාණ්ඩ හමුවේ දුර්වලවී ඇතිබව පෙනේ.විශේෂයෙන් 16,18,31 හා 45 යන වෛරස කාණ්ඩ ඉතා බලවත් බව පර්යේෂකයන් පවසයි.මෙම වෛරස කාණ්ඩ හතර පිළිකා ඇතිකිරීමේ ඉහළ අවධානමක් සහිතය.[25] මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරය නිසා ඇතිවන පිළිකා තත්වය වර්ධනය කිරීමට දුම්පානය හේතුවේ.[26][27] දුම්බීම, දුම්කොළ සැපීම හා වෙනත් දුම්කොළ ආශ්රිත මත්ද්රව්ය භාවිත කිරීම නිසා නිකොටින්,ඇල්කොලොයිඩ් වැනි ප්රබල පිළිකා කාරක ශරීරගතවේ.එමගින් HPV ආසාධිතයන්ට පිළිකා ඇතිවීමේ අවධානම ඉහළයයි.මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස හේතුවෙන් පිළිකා ඇතිවූ බොහෝ දෙනෙක් දුම්පානය,දුම්කොළ සැපීම හා වෙනත් දුම්කොළ ආශ්රිත මත්ද්රව්ය භාවිතා කරන්නන් බව පෙනීගොස් ඇත.

HPV වෛරසය නිසා ඇතිවන පිළිකා සඳහා ජානමය සාධකද ඉතා ඉහළ බලපෑමක් ඇතිකරයි.[28] එබැවින් පවුලේ සමීප ඥාතියෙකුට(ලේ ඥාතියෙකුට) මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් ඇතිවුන පිළිකාවක් ඇතිවූයේනම් ඔවුන්ගේ ඉරදිරි පරපුරේ ඥාතියෙකුට පිළිකා ඇතිවීමේ අවධානම ඉතා ඉහළ මට්ටමක පවතී.උදාහරණ ලෙස තම මවට පියාට හෝ සහෝදර සහෝදරියකට පිළිකාවක් ඇත්නම් තමාටද පිළිකා අවධානම ඇති බව දැනගත යුතුය.[29]

ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා

[සංස්කරණය]ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා ඇතිවීම කෙරෙහි ප්රධාන වශයෙන් බලපාන්නේ HPV16 සහ HPV18, යන වෛරස් කාණ්ඩයි.ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා අතරින් 70% හේතුව මෙම වෛරස කාණ්ඩ දෙකයි.[3][30][31][32]

HPV 16 යන වෛරස කාණ්ඩයේ පිළිකා රෝගීන් ප්රතිශතයක් ලෙස 54% කි.එනම් වැඩිම පිළිකා අවධානමක් ඇති වෛරස කාණ්ඩය HPV 16 බව පැහැදිළිය.[33] ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා වලට අමතරව HPV 16 මගින් ශීශ්නය හා ගුදය ආශ්රිතවද පිළිකා ඇතිකරයි,[34] [35]

ලොවපුරා වැඩිම පිළිකා රෝගී මරණ සංඛ්යාවක් වාර්ථා වන්නේ ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකාව හේතුවෙන්ය.[8] සංවර්ධනය වෙම්න් පවතින රටවල මෙම තත්වය ඉතා ඉහළ අගයක් ගනී.

HPV වෛරසය ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ පද්ධතියේ දුර්වලතා නිසා ඉක්මනින් වර්ධනයවේ.කෙසේ වෙතත් මෙම වෛරසය ආසාධනයවී ඉතා දිගු කලකට පසුව රෝග ලක්ෂණ පහළවීම දක්නට ලැබේ.සාමාන්යයෙන් මෙම කාලය වසර දහයක් හෝ විස්සක් වියහැකිය.[36][37] වර්ථමානයේදී බොහෝ රටවල ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා වළක්වා ගැනීමට වයස අවුරුදු නමයත් දහතුනත් අතර වයසේ පසුවන දැරියන්ට ප්රතිශක්තිකරණ එන්නත ලබාදෙයි.එමගින් මැදිවියේදී ඇතිවියහැකි මාතෘ මරණ ඉතා සාර්ථකව මැඩපවත්වා ගැනීමට හැකිවී ඇත.

ලිංගික අවයව ආශ්රිත පිළිකා

[සංස්කරණය]ගුදය හා ශිශ්නය ආශ්රිත පිළිකා ඇතිකරන HPV වෛරස කාණ්ඩ වැඩිවශයෙන්ම ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේශනය වන බව සොයාගෙන ඇත.විශේෂයෙන් සමලිංගික සබදතා පවත්වන පුරුෂයින් අතර මෙය බහුලව දක්නට ලැබේ.විශේෂයෙන් ගුදය ආශ්රිතව ඇතිවන පිළිකාවලට ප්රබල හේතුවක් ලෙස සමලිංගික ගුද සංසර්ගය හේතුවන බව සොයාගෙන ඇත.[38][39] ඇතැම් සමීක්ෂණයන් අනුව විරුද්ධ ලිංගිකයන් කිහිප දෙනකු ඇසුරු කරන පුරුෂයන් හා එක් සහකාරියක් සමග පමණක් ලිංගික සබදතා පැවැත්වූ පුරුෂයන් අතර පිළිකා තත්වයේ වෙනසක් දක්නට ලැබී නැත.[40].ගුද පිළිකා වැඩි වශයෙන්ම වාර්ථාවන්නේ පුරුෂයන් අතරය..[41] [42][43]

මුඛ හා උගුර ආශ්රිත පිළිකා

[සංස්කරණය]හිස සහ බෙල්ලේ පිළිකා සදහාද HPV 16 සහ HPV 18 යන වෛරස ප්රබල බලපෑමක් එල්ල කරයි.[31] මුඛය හා උගුර ආශ්රිත පිළික ඇතිකරන මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස කාණ්ඩ රැසක්ම ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේශනය වෙයි.දුම්පානය කරන පුද්ගලයන්ට මෙම පිළිකා අවධානම ඉහළ අතර දම්නොබොන පුද්ගලයන්ට පවා කලාතුරකින් මෙම පිළිකා තත්වයන් ඇතිවේ.[44][45] මුඛ හා ගුද ලිංගික සංසර්ගය මගින් එක් අයෙකුගෙන් තවත් අයෙකුට වෛරසය පැතිරේ.HPV- 16 වෛරසය පිළිකා ඇතිවීම කෙරේ ඉහළ බලපෑමක් සිදුකරයි.[46][47] මෙම පිළිකා වර්ධනය කෙරේ දුම්කොළ හා ඇල්කොහොල් වැනි මත්ද්රව්ය හේතුවේ.දුම්කොළ හා දුම්කොළ ආශ්රිත මත්ද්රව්ය හාවිත කිරීම නිසා පිළික තත්වයන් ඉතා භයානක තත්වයන් දක්වා වර්ධනය වියහැකි බව පැවසේ.ඇතැම් පර්යේෂකයන් පෙන්වා දෙන්නේ ඉදිරියේදී ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා අභිබවා මුඛ පිළික නිසා ඇතිවන මරණ සංඛ්යාව ඉහළ යනු ඇති බවයි.[48][49] මෙම නිසා හැකි පමන දුම්කොළ භාවිතය නැවැත්වීමට රජ්ය අංශයේ අවධානය වහාම ලක්වියයුතුය බව පර්යේෂකයන් පෙන්වා දෙයි.ශ්රී ලංකාව හා ඇතැම් දකුණු ආසියාතික රටවලද මුඛ පිළිකා බහුලව දක්නට ලැබේ.මෙයට හේතුව ඔවුන් අතර පවතින බුලත්ටිට කෑම නිසාය.බුලත් විට සදහා යොදා ගන්නා පුවක් වල ඇල්කොලොයිඩ් නම් පිළිකා කාරකයත් දුම්කොළවල නිකොටින් නම් පිළිකා කාරකයත් අඩංගුය.

මෑතකදී ඇමරිකාවේ සිදුකළ පරීක්ෂණවලදී පෙනීගොස් ඇත්තේ HPV 16 වෛරස් කාණ්ඩය නිසා එරට උගුරේ පිළිකා සහිත රෝගීන් සීග්රයෙන් වර්ධනයවී ඇති බවයි.[50] පර්යේෂකයන් පෙන්වා දෙන්නේ මුඛ පිළිකා ඇතිකරන ඇතැම් මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස කාණ්ඩ වැඩි වශයෙන් පැතිරී ඇත්තේ මුඛ සංසර්ගය නිසා බවයි.සාමාන්යයෙන් මුඛ පිළිකා ඇතිවීම කාන්තාවන්ට වඩා පුරුෂයන් අතර බහුලව දක්නට ලැබේ.[51] වර්ථමානයේ ගැහැණු ළමුන් සදහා ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා වළක්වාගැනීමට ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ එන්නත් නිපදවා ඇත.එහෙත් එමගින් උගුරේ ඇතිවන පිළිකා වළක්වාගත නොහැක.[52]

පෙනහළු පිළිකා

[සංස්කරණය]මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය නිසා ඇතිවන පිළිකා අතර පෙනහළු පිළිකාද බහුලව වාර්ථාවන පිළිකා විශේෂයකි.[53] පෙනහළු පිළිකා රෝගීන් බොහෝ දෙනකුට මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ශරීරගතවී තිබුණබව පර්යේෂකයන් පෙන්වාදී ඇත. පෙනහළු පිළිකා ඇතිවීම කෙරේ දුම්පානය ප්රබල හේතුවක්වී ඇත.

ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ ඌනතා

[සංස්කරණය]ඇතැම් පර්යේෂණයන්ට අනුව මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය හේතුවෙන් ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ ඌනතා ඇතිවනබව සොයාගෙන ඇත.මෙම වෛරසය මහින් ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ පද්ධතිය දුර්වල කරන බැවින් කෙරටීන් වැඩි වශයෙන් නිපදවීමත් සම මතුපිට සෛල අසාමාන්ය ලෙස වර්ධනයවීමටත් පටන්ගිනී.මෙහි ප්රථිපල ලෙස සම මතුපිට ඉන්නන් හා තුවාල ඇතිවේ.[54]

හේතුව

[සංස්කරණය]ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේෂණයවන මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස ප්රධාන වශයෙන් කොටස් දෙකකට බෙදා වෙන්කලහැක.ඒ අඩු අවදානම් වෛරස කාණ්ඩ හා වැඩි අවදානම් වෛරස කාණ්ඩ ලෙසයි.අඩු අවදානම් වෛරස කාණ්ඩ මගින් ඉන්නන් ඇතිවීම වැනි සුළු රෝග තත්වයන් පෙන්වන අතර වැඩි අවදානම් කාණ්ඩ මගින් පිළිකා ඇතිකරයි.

ව්යාප්තිය

[සංස්කරණය]නවයොවුන් අවධියේදී ඇතිකරගන්නා ලිංගික සම්භන්දතා හේතුවෙන් බොහෝවිට HPV වෛරසය ශරීරගතවේ.සමලිංගික සංසර්ගයන්,විරුද්ධ ලිංගික සංසර්ගයන්,බහු සහකරු සංසර්ගයන්,දුම්පානය,ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ පද්ධතියේ ඇතිවන දුර්වලතා හේතුවෙන් මෙම වෛරසය ශරීරගතවේ.මෙම වෛරසය ලිංගික ස්රාවයන් හෝ රුධිරය මගින් පමණක් නොව ස්පර්ශයෙන්ද පැතිරේ.අනාරක්ෂිත යොනි හා ගුද සංසර්ගයන් වැඩි අවධානම් මට්ටමක පවතී.මුඛ සංසර්ගය මගින් බෝවීම ඊට සාපේක්ෂව අවම අගයක් ගනී.මවගෙන් දරුවාට වෛරසය ශරීරගතවීම ගැබිනි සමයේදී සිදුවේ.රෝගීන් භාවිතා කළ ඇතැම් දුව්ය උපකරණ හවුලේ භාවිතය මගින් ව්යාප්තිය ඉතා කලාතුරකින් සිදුවන්නකි. [55]

ගර්භනීබව

[සංස්කරණය]මවගෙන් දරුවාට වෛරසය පැතිරීම සිදුවන්නේ HPV ආසාදිත මවක් ගර්භනී සමයේදී ඇගේ කුසතුල සිටින දරුවාට බොවීමයි.එහෙත් ළදරුවකු උපත ලැබූ පසු ඔහුට හෝ ඇයට රෝග ලක්ෂණ ඉක්මනින් පහළ නොවේ.ඇතැම්විට රෝග ලක්ෂණ මතුවීමට වසර විස්සකට වඩා කල්ගතවිය හැක.

ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේෂණය

[සංස්කරණය]ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා ඇතිකරන මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ලිංගිව සම්ප්රේෂණය වෛරස කාණ්ඩ අතර ප්රධාන තැනක් ගනී.කෙසේ වෙතත් මෙම පිළිකාව වැළැක්වීම සදහා එන්නත් ලබාදීම බොහේ රටවල සිදුකෙරේ.එමගින් සාර්ථක ප්රතිපල ලබා ඇත.

HPV වෛරස ප්රථමික ලිංගික ක්රියාවන් මගින් වුවද පැතිරේ.උදාහරණ ලෙස ලිංගික අවයව අතින් ස්පර්ෂ කිරීම දැක්විය හැක.[56]

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස කාණ්ඩ 120 අතරිනුත් 51 පමණ වඩාත් සක්රීය බව සොයාගෙන ඇත.[57] මෙයින් 15 ක් අධි අවදානම් තත්වයේ ඇත.(16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, සහ 82), ඇතැම් කාණ්ඩ මධ්යම අවදානම් මට්ටමක් පෙන්වයි (26, 53, සහ 66), ඇතැම් වෛරක කාණ්ඩ අඩු අවදානම් මට්ටමක් ඇත 12 ,6, 11, 40, 42, 43, 44, 54, 61, 70, 72, 81, සහ1 08).[58]

උපත් පාලන කොපු භාවිතය මෙම වෛරසය සදහා වඩාත් සාර්ථක උපක්රමයක් නොවන්නේ මෙම ඍජු ස්පර්ශය මගින් පවා බෝවන බැවිනි.අනෙක් ලිංගික රෝග ඇතිකරන වෛරස හා බැක්ටීරියා ලිංගික ස්රාව ශ්රක්රාණු,මුත්රා,රුධිරය මගින් ව්යාප්තවන නිසා උපත් පාලක කොපු භාවිතය හොද ආරක්ෂික ක්රමයකි.

අත

[සංස්කරණය]HPV වෛරසය ශරීරගතවීම ආසාදිත පුද්ගලයෙකුගේ ලිංගික පෙදෙස නිරෝගී අයකු අතපතගෑම මගින් හෝ ආසදිතයෙකු නිරෝගී පුද්ගලයෙකුගේ ලිංගික අවයව ස්පර්ශය මගින්ද ව්යාප්තවේ.විරුද්ධ ලිංගිකයන් අතර සිදුවන ලිංගික අවයව ස්පර්ශයේදී ආසාදිත ස්ත්රියක් පුරුෂයෙකුගේ ලිංගික අවයව ස්පර්ශය වැඩි අවදානම් තත්වයත් ලෙස සැළකේ.සමලිංගික සම්භන්දයකදී ආසාදිත පුුරුෂයා හෝ ස්ත්රිය විසින් නිරෝගී ස්ත්රිය හෝ පුරුෂයාගේ ලිංගික අවයව ස්පර්ශ කිරීම වැඩි අවදානම් සහිතය.කෙසේ වෙතත් යොනි,ගුද හා මුඛ සංසර්ගයන්ට සාපේක්ෂව අතපතගෑමෙන් වෛරස ආසාදනයවීම ඉතා අවම අගයක් ගනී.අතින් ලිංගික අවයවයන් ස්පර්ශයේදී පුරුෂයන්ගේ අතින් සිදුකරන ස්පපර්ශයන් වඩාත් අවදානම් සහගතය. ලිංගික නොවන අතපතගෑම් වලදී ද මීට සමාන තත්වයක් ඇත.

ද්රව්ය

[සංස්කරණය]ඇතැම් ද්රව්ය උපකරණ හවුලේ භාවිතා කිරීම මගින්ද මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ව්යාප්තවිය හැක.උදාහරණ ලෙස රැවුල කපන උපකරණ,දත් බුරුසු ආදිය දැක්විය හැක.[59][60][61] ඇතැම් විට ස්වංවින්දනය සදහා ස්ත්රීන් භාවිත කරන කෘතිම ශිශ්න ආදිය හවුලේ භාවිතය මගින් ද මෙ පැතිරිය හැක.[62]

රුධිරය

[සංස්කරණය]මීට ඉහතදී පර්යේෂකයන් විශ්වාස කළේ මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය රුධිරය මගින් බෝ නොවන බවයි.එහෙත් නවතම අධ්යනයන්ට අනුව මෙම වෛරසය රුධිරය මගින්ද බෝවන බව සොයාගෙන ඇත.[63] මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස ආසාධිතපුද්ගලයන් ගෙන් ලබාගත් රුධිර සාම්පල ශිතකරණයක රදවා පසුව නැවත පරික්ෂා කිරීමේදී තවමත් සජීවී තත්වයේ සිටි වෛරස හමුවී ඇත.[64] එමගින් රුධිර පාරවිලනය මගින් මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය පැතිරෙන බව ප්රත්යක්ෂවී ඇත.2009 දී ඕස්ට්ර්ලියාවේ රතු කුරුස සංවිධානය මගින් සංවිධානය කළ ලේ දන්දීමේ වැඩසටහනකදී පුරුෂයන් ගෙන් ලබාගත් රුධිර සාම්පල තුල සජීවී මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස අඩංගුවී තිබී ඇත.[65]

සැත්කම්

[සංස්කරණය]ඇතැම් සැත්කම් සිදුකිරීමේදී ජීවානුහරණය නොකළ ශල්ය උපකරණ පොදුවේ භාවිත කිරීමේදී මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ශරීරගතවිය හැක..[66]

වෛරස අධ්යනය

[සංස්කරණය]| මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය | |

|---|---|

| |

| TEM of papillomavirus | |

| වෛරස වර්ගීකරණය | |

| Group: | කාණ්ඩය I (dsDNA) |

| ගෝත්රය: | Unassigned |

| කුලය: | Papillomaviridae |

| Genera | |

|

Alphapapillomavirus | |

HPV වෛරසය සජීවී පටක තුල නොව අජීවී පටක තුල වර්ධනයවේ.මෙම වෛරසය ආසාදනයවීම සිදුවන්නේ ඉතා සෙමිනි.ලිංගික සංසර්ගයකින් හෝ සමෙහි ඇතිවන තුවාලයකින් සීරීමක් තුලින් වෛරසය ශරීරයට ඇතුළු වෙයි.රෝග ලක්ෂණ පහළවීමද ඉතා සෙමින් සිදුවේ.

රෝග නිර්නය

[සංස්කරණය]මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස ප්රධාව වශයෙන් එහි බලපෑම් මත කොටස් දෙකකට බෙදේ.එක් වර්ගයක් අඩු අවදානම් සහිත වන අතර එමගින් ඉන්නන් ඇතිවීම වැනි සුළු ආබාධ පමණක් ඇතිවේ.අනෙත් වර්ගය වැඩි අවදානම් සහිත වෛරස වන අතර එම වෛරස මගින් පිළිකා ඇතිකරයි.[67]

සෞඛය අංශ පෙන්වා දෙන්නේ මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය ශරීරගතවී ඇතැයි සක කරන ලක්ෂණ පහලවූ වහාම ඒ සම්භන්දව වෛද්ය පරීක්ෂණ වෙත යොමුවීම වැදගත් බවයි.

ගැබ්ගෙල පර්ක්ෂාව

[සංස්කරණය]HPV වෛරසය ශරීරගතවී ඇතිබව දැනගත්විට එම වෛරසය HPV 16හෝ17 ද යන්න DNA පරීක්යෂණයන්න මගින් සනාථ කරගත හැකිය. කාණ්ඩයන්ට අයත් වෛරස මගින් ගැබ්ගෙ පිළිකා ඇතිකරනු ලබයි.

“Theoretically, the HPV DNA and RNA tests could be used to identify HPV infections in cells taken from any part of the body. However, the tests are approved by the FDA for only two indications: for follow-up testing of women who seem to have abnormal Pap test results and for cervical cancer screening in combination with a Pap test among women over age 30.” [68]

In April 2011, the Food and Drug Administration approved the cobas HPV Test, manufactured by Roche.[69] This cervical cancer screening test “specifically identifies types HPV 16 and HPV 18 while concurrently detecting the rest of the high risk types (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68).”

The cobas HPV Test was evaluated in the ATHENA trial, which studied more than 47,000 U.S. women 21 years old and older undergoing routine cervical cancer screening.[70] Results from the ATHENA trial demonstrated that 1 in 10 women, age 30 and older, who tested positive for HPV 16 and/or 18, actually had cervical pre-cancer even though they showed normal results with the Pap test.

In March 2003, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the Hybrid Capture 2 test manufactured by Qiagen/Digene,[71] which is a "hybrid-capture" test[72][73] as an adjunct to Pap testing. The test may be performed during a routine Pap smear. It detects the DNA of 13 "high-risk" HPV types that most commonly affect the cervix, it does not determine the specific HPV types. Hybrid Capture 2 is the most widely studied commercially available HPV assay and the majority of the evidence for HPV primary testing in population-based screening programs is based on the Hybrid Capture 2 assay.[74]

The recent outcomes in the identification of molecular pathways involved in cervical cancer provide helpful information about novel bio- or oncogenic markers that allow monitoring of these essential molecular events in cytological smears, histological, or cytological specimens. These bio- or onco- markers are likely to improve the detection of lesions that have a high risk of progression in both primary screening and triage settings. E6 and E7 mRNA detection PreTect HPV-Proofer (HPV OncoTect) or p16 cell-cycle protein levels are examples of these new molecular markers. According to published results, these markers, which are highly sensitive and specific, allow to identify cells going through malignant transformation.[75][76]

In October 2011 the US Food and Drug Administration approved the Aptima HPV Assay test for RNA created when and if any HPV strains start creating cancers (see virology).[77][78][79]

The vulva/vagina has been sampled with Dacron swabs and shows more HPV than the cervix. Among women who were HPV positive in either place, 90% were positive in the vulvovaginal region, 46% in the cervix.

මුඛය පරික්ෂාව

[සංස්කරණය]මුඛය පිරිමැදීමෙන් ලබාගන්නා සෛල සම්පල විද්යාගරයකදී පරික්ෂාකර එහි ඇති HPV වෛරසය පවතින්නේනම් එම වෛරස වැඩි අවදානම් කාණ්ඩයට අයත් දැයි පරික්ෂා කරගත හැකි.

පුරුෂයන්

[සංස්කරණය]පර්යේෂකයන්ට අනුව ඇඟිලි,මුඛය,ඛේටය,ගුදය,මුත්ර මාර්ගය,මුත්රා,ශුක්රාණු,රුධිරය,වෘෂණ හා ශිශ්නය ආශ්රිතව මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය හමුවන බවයි.මෙම පෙදෙස් හා ස්රාවයන් ස්පර්ශයෙන් ආසාධිතයකුගේ සිට නිරෝගී පුද්ගලයෙකුට වෛරසය පැතිරේ

බ්රසීලය තුල සිදුකල පර්යේෂණයකට අනුව වැඩි වශයෙන්ම ශිශ්නය හා වෘෂණ ආශ්රිතව වෛරස වැඩි වශයෙන් පවතිනබව සොයාගෙන ඇත.ශිශ්න-යෝනි හෝ ශිශ්න-ගුද සංසර්ගයන් තුලින් වැඩි වශයෙන් වෛරසය පැතිරේ.මෙසේ ශිශ්නය මගින් වෛරස පැතිරීම වැළැක්වීමට සංසර්ගයට පෙර ශිශ්නය විෂබීජ නාශක යොදා පිරිසිදු කිරීම හෝ උපත් පාලන කොපු පැළදීම වඩාත් සුදුසුය.

කේසිකානු පර්යේෂණ ක්ණ්ඩායමක් විසින් පුරුෂයන්ගේ ශීශ්නය කුඩා බුරුසුවකින් පිරිමැදීමෙන් ලබාගත් සෛල සාම්පලවල සජීවී HPV වෛරස දැකගතහැකිවිය පසුව ඔවුන් එම පුරුෂයන්ට තම ශිශ්නය හොදින් පිරිසිදු කර ගන්නා ලෙස උපදෙස්දී පැය 12 කට කලින් යලින් සෛල සාම්පල රැගෙන පරික්ෂා කළහ.එහිදී ඔවුන්ට කලින්ට වඩා ඉතා අඩු වෛරස ප්රතිශතයක් දැකගත හැකිවිය.ඒ අනුව සංසර්ගයට පෙර ශිශ්නය පිරිසිදුව තබා ගැනීම මගින් මෙම වෛරසය ව්යාප්තිය පාලනය කලහැකිබව ඔවුන් පෙන්වා දුන්හ.[80]

වෙනත්

[සංස්කරණය]Although it is possible to test for HPV DNA in other kinds of infections,[81] there are no FDA-approved tests for general screening in the United States or tests approved by the Canadian government,[82] since the testing is inconclusive and considered medically unnecessary.[83]

Genital warts are the only visible sign of low-risk genital HPV and can be identified with a visual check. These visible growths, however, are the result of non-carcinogenic HPV types. Five percent acetic acid (vinegar) is used to identify both warts and squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (SIL) lesions with limited success[තහවුරු කර නොමැත] by causing abnormal tissue to appear white, but most doctors have found this technique helpful only in moist areas, such as the female genital tract.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත] At this time, HPV test for males are used only in research.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

Research into testing for HPV by antibody presence has been done. The approach is looking for an immune response in blood, which would contain antibodies for HPV if the patient is HPV positive.[84][85][86][87] The reliability of such tests hasn't been proven, as there hasn't been a FDA approved product as of March 2014; testing by blood would be a less invasive test for screening purposes.

වැලැක්වීම

[සංස්කරණය]The HPV vaccines can prevent the most common types of infection.[6] To be effective they must be used before an infection occurs and are therefore recommended between the ages of nine and thirteen. Cervical cancer screening, such as with the Papanicolaou test (pap) or looking at the cervix after using acetic acid, can detect early cancer or abnormal cells that may develop into cancer. This allows for early treatment which results in better outcomes. Screening has reduced both the number and deaths from cervical cancer in the developed world.[7] Warts can be removed by freezing.

Methods of reducing the chances of infection include sexual abstinence,[තහවුරු කර නොමැත] condoms, vaccination, and microbicides.

එන්නත්

[සංස්කරණය]HPV වෛරසය නිසා ඇතිවන පිළිකා වළක්වා ගැනීම සදහා භාවිත කරන එන්නත් වර්ග තුනක් ඇත. ඒවා නම් ගාඩෙසිල්( Gardasil), සර්වැරික්ස්(Cervarix), සහ ගාඩෙසිල් 9 (Gardasil 9) එන්නත්ය. මේ සියල්ලෙස් HPV 16 සහ 18 නිසා ඇතිවන පිළිකා වලින් ආරක්ෂාව සපයයි.ගාඩෙසිල් එන්නත HPV 6 11 වලින්ද ආරක්ෂාව සපයයි..මෙම එන්නත් මගින් සාර්ථකවම වලක්වාගත හැක්කේ ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකාවයි.[88] මෙම එන්නත් මගින් අනෙකුත් පිළිකාද වළක්වා ගැනීමේ හැකියාව පවතී.

දැනටමත් වෛරසය ශරීරගතවී ඇත්නම් ප්රතිශක්තීකරන එන්නත් මගින් නිසි ඵල ලබාගත නොහැකිය.[89] සාර්ථක ප්රථිපල සදහා වෛරසය ශරීරගතවීමට ප්රථම එන්නත් ලබාදිය යුතුය.[90]

The CDC recommends the vaccines be delivered in two shots, with an interval of at least 6 months between them, for those who are 11 to 12, and three doses for those who are older.[91] In most countries, they are funded only for female use, but are approved for male use in many countries, and funded for teenage boys in Australia. The vaccine does not have any therapeutic effect on existing HPV infections or cervical lesions. In 2010, 49% of teenage girls in the US got the HPV vaccine.

Following studies suggesting that the vaccine is more effective in younger girls[92] than in older teenagers, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Mexico, the Netherlands and Quebec began offering the vaccine in a two-dose schedule for girls aged under 15 in 2014.

Cervical cancer screening recommendations have not changed for females who receive HPV vaccine. It remains a recommendation that women continue cervical screening, such as Pap smear testing, even after receiving the vaccine, since it does not prevent all types of cervical cancer.[93][94]

Both men and women are carriers of HPV.[95] The Gardasil vaccine also protects men against anal cancers and warts and genital warts.[96]

Duration of both vaccines' efficacy has been observed since they were first developed, and is expected to be longlasting.[97]

In December 2014, the FDA approved a nine-valent Gardasil-based vaccine, Gardasil 9, to protect against infection with the four strains of HPV covered by the first generation of Gardasil as well as five other strains responsible for 20% of cervical cancers (HPV-31, HPV-33, HPV-45, HPV-52, and HPV-58).[98]

උපත් පාලන කොපු

[සංස්කරණය]මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරස ව්යාප්තිය වැළැක්වීමේ ඉතා සාර්තක ක්රමයක් ලෙස උපත් පාලන කොපු දැක්වියහැක.කෙසේ වෙතත් මෙම වෛරසය අනෙකුත් ලිංගිකව සම්ප්රේෂණයවන රෝග මෙන් ලිංගික ස්රාවයන් හා රුධිරය මගින් පමණක් ව්යාප්ත නොවන බැවින් අනෙකුත් වෛරස හා සාපේක්ෂව සංකීර්ණ ස්වභාවයක් ගනී.කෙසේ වෙතත් වැඩි අවධානමක් සහිත HPV වෛරස කාණ්ඩ ස්පර්ශයෙන් බොනොවේ.[99]

උපත් පාලන කොපු අතරින් පුරුෂයන් භාවිත කරන උපත් පාලන කොපු වලට වඩා කාන්තාවන් භාවිතා කරන උපත් පාලන කොපු වඩා ආරක්ෂිතය.[100]

බොහෝ අධ්යනයන්ට උපත් පාලන කොපු භාවිත කරමින් සංසර්ගයේ යෙදුනද පුද්ගලයන්ට වෛරස ආසාදනය ඉතාමත් අවම මට්ටමක පවතීනබව ප්රත්යක්ෂවී ඇත.

විෂබීජනාශක

[සංස්කරණය]මෙම වෛරසය විෂබීජ නාශක මගින් විනාශ කිරීම අපහසුය.එතනෝල් මගින් විනාඩියක් පමණ සේදීමෙන් 90% පමණ වෛරස විනාශ කළහැක.මීට අමතරව වෙනත් විශබීජ නාශක මගින් ඉතා සුළු වශයෙන් වෛරසය අඩපන කළහැක.[101]

මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය වියළ හා උණුසුම් පරිසරයන්හිදී උදාසීනවේ.100 °C (212 °F) වැනි උෂ්ණත්වයකදී මෙම වෛරසය සම්පූර්ණයෙන්ම විනාශවේ.මීට අමතරව පාලජම්බුල කිරණ මගින්ත ඉතා සාර්තකව විනාශ කළහැක.

ප්රතිකාර

[සංස්කරණය]මානව පැපිලෝමා වෛරසය සදහා ප්රත්යක්ෂ ප්රතිකාරයක් තවම සොයාගෙන නැත.[102][103][104] එහෙත් වෛරස ආසාදනය ලක්වූවන්ට වඩා ප්රතිපලදායක ඖෂධ පවතී.[105] මෙම වෛරසය ආසාදනයෙන් පසු රෝග ලක්ෂණ ඇතිවීමට දීර්ඝ කාලයක් ගතවන බැවින් කලින් හදුනාගැනීම අපහසුය.[106] ගැබ්ගෙල පිළිකා වැළැක්වීමට වර්තමානයේ ප්රතිශක්තීකරණ එන්නත් සාර්ථකව භාවිතවේ.

වසංගතවේදය

[සංස්කරණය]Worldwide, HPV is estimated to infect about 12% of women at any given time.[107] HPV infection is the most frequently sexually transmitted disease in the world.[108]

ඇමරිකාව

[සංස්කරණය]| Age (years) | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

| 14 to 19 | 24.5% |

| 20 to 24 | 44.8% |

| 25 to 29 | 27.4% |

| 30 to 39 | 27.5% |

| 40 to 49 | 25.2% |

| 50 to 59 | 19.6% |

| 14 to 59 | 26.8% |

HPV is estimated to be the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. Most sexually active men and women will probably acquire genital HPV infection at some point in their lives.[109] The American Social Health Association estimates that about 75–80% of sexually active Americans will be infected with HPV at some point in their lifetime.[110][111] By the age of 50 more than 80% of American women will have contracted at least one strain of genital HPV.[112][113] It was estimated that, in the year 2000, there were approximately 6.2 million new HPV infections among Americans aged 15–44; of these, an estimated 74% occurred to people between ages of 15 and 24.[114] Of the STDs studied, genital HPV was the most commonly acquired. In the United States, it is estimated that 10% of the population has an active HPV infection, 4% has an infection that has caused cytological abnormalities, and an additional 1% has an infection causing genital warts.[115]

Estimates of HPV prevalence vary from 14% to more than 90%.[116] One reason for the difference is that some studies report women who currently have a detectable infection, while other studies report women who have ever had a detectable infection.[117][118] Another cause of discrepancy is the difference in strains that were tested for.

One study found that, during 2003–2004, at any given time, 26.8% of women aged 14 to 59 were infected with at least one type of HPV. This was higher than previous estimates; 15.2% were infected with one or more of the high-risk types that can cause cancer.[119]

The prevalence for high-risk and low-risk types is roughly similar over time.

Human papillomavirus is not included among the diseases that are typically reportable to the CDC as of 2011.[120][121]

යොමුව

[සංස්කරණය]- ^ Milner, Danny A. (2015). Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 40. ISBN 9780323400374. 11 සැප්තැම්බර් 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ljubojevic, Suzana; Skerlev, Mihael (2014). "HPV-associated diseases". Clinics in Dermatology. 32 (2): 227–234. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.08.007. ISSN 0738-081X. PMID 24559558.

- ^ a b "Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer". WHO. ජූනි 2016. 5 අගෝස්තු 2016 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 අගෝස්තු 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Link Between HPV and Cancer". CDC. September 30, 2015. 9 November 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Pink Book (Human Papillomavirus)" (PDF). CDC.gov. 21 මාර්තු 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 අප්රේල් 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "What is HPV?". CDC. 28 දෙසැම්බර් 2015. 7 අගෝස්තු 2016 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 අගෝස්තු 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sawaya, GF; Kulasingam, S; Denberg, TD; Qaseem, A; Clinical Guidelines Committee of American College of, Physicians (16 ජූනි 2015). "Cervical Cancer Screening in Average-Risk Women: Best Practice Advice From the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (12): 851–9. doi:10.7326/M14-2426. PMID 25928075. 5 මැයි 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.12. ISBN 9283204298.

- ^ "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Questions and Answers". CDC. 28 දෙසැම්බර් 2015. 11 අගෝස්තු 2016 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 11 අගෝස්තු 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tyring, Stephen; Moore, Angela Yen; Lupi, Omar (2016). Mucocutaneous Manifestations of Viral Diseases: An Illustrated Guide to Diagnosis and Management (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්) (2 ed.). CRC Press. p. 207. ISBN 9781420073133. 11 සැප්තැම්බර් 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ EHPV, archived from the original on 17 December 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20141217090044/http://ehpv.org/.

- ^ Bzhalava, D; Guan, P; Franceschi, S; Dillner, J; Clifford, G (2013), "A systematic review of the prevalence of mucosal and cutaneous human papillomavirus types", Virology 445 (1–2): 224–31, , .

- ^ Muñoz, N; Bosch, F. X.; De Sanjosé, S; Herrero, R; Castellsagué, X; Shah, K. V.; Snijders, P. J.; Meijer, C. J. et al. (2003), "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer", The New England Journal of Medicine 348 (6): 518–27, , , archived from the original on 30 April 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20120430053849/http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa021641

- ^ Palefsky, Joel M.; Holly, Elizabeth A.; Ralston, Mary L.; Jay, Naomi (පෙබරවාරි 1988). "Prevalence and Risk Factors for Human Papillomavirus Infection of the Anal Canal in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)–Positive and HIV-Negative Homosexual Men". Departments of Laboratory Medicine, Stomatology, and Epidemiology Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco. The Journal of Infectious Diseases Oxford University Press. 15 ජනවාරි 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2 මාර්තු 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Mitchell, Richard (2007). "Chapter 19 The Female Genital System and Breast". Robbins Basic Pathology (8 ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

- ^ Muñoz N, Castellsagué X, de González AB, Gissmann L; Castellsagué; De González (2006). "Chapter 1: HPV in the etiology of human cancer". Vaccine. 24 (3): S1–S10. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.115. PMID 16949995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Antonsson A, Forslund O, Ekberg H, Sterner G, Hansson BG (2000). "The ubiquity and impressive genomic diversity of human skin papillomaviruses suggest a commensalic nature of these viruses". J. Virol. 74 (24): 11636–41. doi:10.1128/JVI.74.24.11636-11641.2000. PMC 112445. PMID 11090162.

- ^ Mayo Clinic.com, Common warts, http://www.mayoclinic.com/print/common-warts/DS00370/DSECTION=all&METHOD=print සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 17 ඔක්තෝබර් 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De Koning MN, Quint KD, Bruggink SC, Gussekloo J, Bouwes Bavinck JN, Feltkamp MC, Quint WG, Eekhof JA (2014). "High prevalence of cutaneous warts in elementary school children and ubiquitous presence of wart-associated HPV on clinically normal skin". The British Journal of Dermatology. 172: 196–201. doi:10.1111/bjd.13216. PMID 24976535.

- ^ Lountzis NI, Rahman O (2008). "Images in clinical medicine. Digital verrucae". N. Engl. J. Med. 359 (2): 177. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm071912. PMID 18614785.

- ^ MedlinePlus, Warts, https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/warts.html#cat42 සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 5 ජූනි 2016 at the Wayback Machine (general reference with links). Also, see

- ^ Greer CE, Wheeler CM, Ladner MB, Beutner K, Coyne MY, Liang H, Langenberg A, Yen TS, Ralston R (1995). "Human papillomavirus (HPV) type distribution and serological response to HPV type 6 virus-like particles in patients with genital warts". J. Clin. Microbiol. 33 (8): 2058–63. PMC 228335. PMID 7559948.

- ^ Parkin DM (2006). "The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002". Int. J. Cancer. 118 (12): 3030–44. doi:10.1002/ijc.21731. PMID 16404738.

- ^ "Archived copy". 24 අගෝස්තු 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 අගෝස්තු 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)(subscription required) - ^ Schiffman M, Castle PE (2005). "The promise of global cervical-cancer prevention". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (20): 2101–4. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058171. PMID 16291978.

- ^ Alam S, Conway MJ, Chen HS, Meyers C (2007). "Cigarette Smoke Carcinogen Benzo[a]pyrene Enhances Human Papillomavirus Synthesis". J Virol. 82 (2): 1053–8. doi:10.1128/JVI.01813-07. PMC 2224590. PMID 17989183.

- ^ Lu B, Hagensee ME, Lee JH, Wu Y, Stockwell HG, Nielson CM, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss M, Harris RB, Giuliano AR (February 2010). "Epidemiologic factors associated with seropositivity to human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 virus-like particles and risk of subsequent infection in men". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 19 (2): 511–6. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0790. PMID 20086109.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (help) - ^ Liu, Ying (2015). "Comprehensive mapping of the human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA integration sites in cervical carcinomas by HPV capture technology". Oncotarget. 7: 5852–5864. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.6809. PMC 4868726. PMID 26735580.

- ^ Parfenov, Michael (2014). "Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111: 15544–15549. doi:10.1073/pnas.1416074111. PMC 4217452. PMID 25313082.

- ^ Cohen J (2005). "Public health. High hopes and dilemmas for a cervical cancer vaccine". Science. 308 (5722): 618–21. doi:10.1126/science.308.5722.618. PMID 15860602.

- ^ a b Ault KA (2006). "Epidemiology and Natural History of Human Papillomavirus Infections in the Female Genital tract". Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006: 1–5. doi:10.1155/IDOG/2006/40470. PMC 1581465. PMID 16967912.

- ^ Kreimer, Aimee R.; Clifford, Gary M.; Boyle, Peter; Franceschi, Silvia (1 February 2005). "Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 14 (2): 467–475. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0551. ISSN 1055-9965. PMID 15734974.

- ^ Noel J, Lespagnard L, Fayt I, Verhest A, Dargent J (2001). "Evidence of human papilloma virus infection but lack of Epstein-Barr virus in lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of uterine cervix: report of two cases and review of the literature". Hum. Pathol. 32 (1): 135–8. doi:10.1053/hupa.2001.20901. PMID 11172309.

- ^ "Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia: Varied signs, varied symptoms: what you need to know". www.advanceweb.com. 16 ජූලි 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 5 අගෝස්තු 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bolt J, Vo QN, Kim WJ, McWhorter AJ, Thomson J, Hagensee ME, Friedlander P, Brown KD, Gilbert J (2005). "The ATM/p53 pathway is commonly targeted for inactivation in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) by multiple molecular mechanisms". Oral Oncol. 41 (10): 1013–20. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.06.003. PMID 16139561.

- ^ Sinal SH, Woods CR (2005). "Human papillomavirus infections of the genital and respiratory tracts in young children". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 16 (4): 306–16. doi:10.1053/j.spid.2005.06.010. PMID 16210110.

- ^ Greenblatt, R. J. (2005). "Human papillomaviruses: Diseases, diagnosis, and a possible vaccine". Clinical Microbiology Newsletter. 27 (18): 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2005.09.001.

- ^ "HPV and Men — CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 3 අප්රේල් 2008. 17 ඔක්තෝබර් 2009 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 නොවැම්බර් 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Frisch M, Smith E, Grulich A, Johansen C (2003). "Cancer in a population-based cohort of men and women in registered homosexual partnerships". Am. J. Epidemiol. 157 (11): 966–72. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg067. PMID 12777359. 19 මැයි 2009 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

However, the risk for invasive anal squamous carcinoma, which is believed to be caused by certain types of sexually transmitted human papillomaviruses, a notable one being type 16, was significantly 31-fold elevated at a crude incidence of 25.6 per 100,000 person-years

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas W. Gaither; et al. (2015). "The Influence of Sexual Orientation and Sexual Role on Male Grooming-Related Injuries and Infections". J Sex Med. 12 (3): 631–640. doi:10.1111/jsm.12780.

- ^ Chin-Hong PV, Vittinghoff E, Cranston RD, Browne L, Buchbinder S, Colfax G, Da Costa M, Darragh T, Benet DJ, Judson F, Koblin B, Mayer KH, Palefsky JM (2005). "Age-related prevalence of anal cancer precursors in homosexual men: the EXPLORE study". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97 (12): 896–905. doi:10.1093/jnci/dji163. PMID 15956651.

- ^ "AIDSmeds Web Exclusives : Pap Smears for Anal Cancer? — by David Evans". AIDSmeds.com. 7 ජූලි 2011 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 29 අගෝස්තු 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Goldie SJ, Kuntz KM, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA, Palefsky JM (June 2000). "Cost-effectiveness of screening for anal squamous intraepithelial lesions and anal cancer in human immunodeficiency virus-negative homosexual and bisexual men". Am. J. Med. 108 (8): 634–41. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00349-1. PMID 10856411.

- ^ Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, Spafford M, Westra WH, Wu L, Zahurak ML, Daniel RW, Viglione M, Symer DE, Shah KV, Sidransky D (2000). "Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92 (9): 709–20. doi:10.1093/jnci/92.9.709. PMID 10793107.

- ^ Gillison ML (2006). "Human papillomavirus and prognosis of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: implications for clinical research in head and neck cancers". J. Clin. Oncol. 24 (36): 5623–5. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1829. PMID 17179099.

- ^ D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, Westra WH, Gillison ML (2007). "Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (19): 1944–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa065497. PMID 17494927. 12 මැයි 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ridge JA, Glisson BS, Lango MN, et al. "Head and Neck Tumors" සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 20 ජූලි 2009 at the Wayback Machine in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 4 ඔක්තෝබර් 2013 at the Wayback Machine. 11 ed. 2008.

- ^ "Oral Cancer on the rise among non-smokers under 50" (PDF). California Dental Hygienists’ Association. 24 ජනවාරි 2011 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 ජනවාරි 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Chaturvedi, Anil K.; Engels, Eric A.; Pfeiffer, Ruth M.; Hernandez, Brenda Y.; Xiao, Weihong; Kim, Esther; Jiang, Bo; Goodman, Marc T.; Sibug-Saber, Maria (10 November 2011). "Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (32): 4294–4301. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. ISSN 1527-7755. PMC 3221528. PMID 21969503.

- ^ Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, Jiang B, Goodman MT, Sibug-Saber M, Cozen W, Liu L, Lynch CF, Wentzensen N, Jordan RC, Altekruse S, Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Gillison ML (October 2011). "Human Papillomavirus and Rising Oropharyngeal Cancer Incidence in the United States". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (32): 4294–301. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. PMC 3221528. PMID 21969503.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (help) - ^ Ernster JA, Sciotto CG, O'Brien MM, Finch JL, Robinson LJ, Willson T, Mathews M (December 2007). "Rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer and the role of oncogenic human papilloma virus". The Laryngoscope. 117 (12): 2115–28. doi:10.1097/MLG.0b013e31813e5fbb. PMID 17891052.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (help) - ^ Kidon MI, Shechter E, Toubi E (January 2011). "[Vaccination against human papilloma virus and cervical cancer]". Harefuah (Hebrew බසින්). 150 (1): 33–6, 68. PMID 21449154.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Lung Cancer Risk Rises in the Presence of HPV Antibodies". Lung Cancer Risk Rises in the Presence of HPV Antibodies. 27 අප්රේල් 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Moore, Matthew (12 නොවැම්බර් 2007). "Tree man 'who grew roots' may be cured". The Daily Telegraph. London. 13 නොවැම්බර් 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Heymann, MD, David (2015). Control of Communicable Diseases Manual (20th ed.). Washington D.C.: Apha Press. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-0-87553-018-5.

- ^ Burchell AN, Winer RL, de Sanjosé S, Franco EL (Aug 2006). "Chapter 6: Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of genital HPV infection". Vaccine. 24 Suppl 3: S3/52–61. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.031. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 16950018.

- ^ Schmitt M, Depuydt C, Benoy I, Bogers J, Antoine J, Arbyn M, Pawlita M (2012). "Prevalence and viral load of 51 genital human papillomavirus types and 3 subtypes". Int J Cancer. 132: 2395–2403. doi:10.1002/ijc.27891.

- ^ Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ (2003). "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (6): 518–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641. PMID 12571259.

- ^ Tay SK (ජූලි 1995). "Genital oncogenic human papillomavirus infection: a short review on the mode of transmission". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 24 (4): 598–601. ISSN 0304-4602. PMID 8849195. 27 ජූලි 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත (Free full text) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pao CC, Tsai PL, Chang YL, Hsieh TT, Jin JY (Mar 1993). "Possible non-sexual transmission of genital human papillomavirus infections in young women". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 12 (3): 221–222. doi:10.1007/BF01967118. ISSN 0934-9723. PMID 8389707.

- ^ Tay SK, Ho TH, Lim-Tan SK (අගෝස්තු 1990). "Is genital human papillomavirus infection always sexually transmitted?". The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 30 (3): 240–242. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1990.tb03223.x. ISSN 0004-8666. PMID 2256864. 6 අප්රේල් 2016 දින මුල් පිටපත (Free full text) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sonnex C, Strauss S, Gray JJ (October 1999). "Detection of human papillomavirus DNA on the fingers of patients with genital warts". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 75 (5): 317–319. doi:10.1136/sti.75.5.317. ISSN 1368-4973. PMC 1758241. PMID 10616355.

- ^ Hans Krueger; Gavin Stuart; Richard Gallagher; Dan Williams, Jon Kerner (12 අප්රේල් 2010). HPV and Other Infectious Agents in Cancer:Opportunities for Prevention and Public Health: Opportunities for Prevention and Public Health. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-973291-3. 9 ජූනි 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 දෙසැම්බර් 2012.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bodaghi S, Wood LV, Roby G, Ryder C, Steinberg SM, Zheng ZM (November 2005). "Could human papillomaviruses be spread through blood?". J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 (11): 5428–34. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.11.5428-5434.2005. PMC 1287818. PMID 16272465.

- ^ Chen AC, Keleher A, Kedda MA, Spurdle AB, McMillan NA, Antonsson A (October 2009). "Human papillomavirus DNA detected in peripheral blood samples from healthy Australian male blood donors". J. Med. Virol. 81 (10): 1792–6. doi:10.1002/jmv.21592. PMID 19697401.

- ^ Watson RA (2005). "Human Papillomavirus: Confronting the Epidemic—A Urologist's Perspective". Rev Urol. 7: 135–44. PMC 1477576. PMID 16985824.

- ^ Schiffman M, Castle PE; Castle (August 2003). "Human papillomavirus: epidemiology and public health". Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 127 (8): 930–4. doi:10.1043/1543-2165(2003)127<930:HPEAPH>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1543-2165. PMID 12873163.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet: HPV and Cancer". Cancer.gov. 31 ඔක්තෝබර් 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 23 ඔක්තෝබර් 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "FDA Approval of cobas HPV Test – P1000020". U.S Food and Drug Administration. 15 පෙබරවාරි 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 23 ඔක්තෝබර් 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wright TC, Stoler MH, Sharma A, Zhang G, Behrens C, Wright TL (2011). "Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 136 (4): 578–586. doi:10.1309/ajcptus5exas6dkz. PMID 21917680.

- ^ Digene HPV HC2 DNA Test සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 27 අගෝස්තු 2010 at the Wayback Machine Qiagen HPV test

- ^ "Qiagen to Buy Digene, Maker of Tests for Cancer-Causing Virus". The New York Times. 4 ජූනි 2007. 30 ජූනි 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "So Close Together for So Long, and Now One". The Washington Post. 20 අගෝස්තු 2007. 6 ජූලි 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ronco G (2014). "Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials". The Lancet. 383: 524–532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7.

- ^ Wentzensen N, von Knebel Doeberitz M (2007). "Biomarkers in cervical cancer screening". Dis. Markers. 23 (4): 315–30. doi:10.1155/2007/678793. PMID 17627065.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Molden T, Kraus I, Skomedal H, Nordstrøm T, Karlsen F (June 2007). "PreTect HPV-Proofer: real-time detection and typing of E6/E7 mRNA from carcinogenic human papillomaviruses". J. Virol. Methods. 142 (1–2): 204–12. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.01.036. PMID 17379322.

- ^ FDA approval of APTIMA HPV Assay - P100042 සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 14 දෙසැම්බර් 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dockter J, Schroder A, Hill C, Guzenski L, Monsonego J, Giachetti C (2009). "Clinical performance of the APTIMA® HPV Assay for the detection of high-risk HPV and high-grade cervical lesions". Journal of Clinical Virology. 45: S55–S61. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(09)70009-5. PMID 19651370.

- ^ "Press". gen-probe.com. 12 දෙසැම්බර් 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Aguilar LV, Lazcano-Ponce E, Vaccarella S, Cruz A, Hernández P, Smith JS, Muñoz N, Kornegay JR, Hernández-Avila M, Franceschi S (2006). "Human papillomavirus in men: Comparison of different genital sites". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (1): 31–33. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.015131. PMC 2563819. PMID 16461598.

- ^ Dunne EF, Nielson CM, Stone KM, Markowitz LE, Giuliano AR (2006). "Prevalence of HPV infection among men: A systematic review of the literature". J. Infect. Dis. 194 (8): 1044–57. doi:10.1086/507432. PMID 16991079.

- ^ "Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Men: Questions and Answers". 2007. 14 සැප්තැම්බර් 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 සැප්තැම්බර් 2008.

Currently, in Canada there is an HPV DNA test approved for women but not for men.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "What Men Need to Know About HPV". 2006. 7 අප්රේල් 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 අප්රේල් 2007.

There is currently no FDA-approved test to detect HPV in men. That is because an effective, reliable way to collect a sample of male genital skin cells, which would allow detection of HPV, has yet to be developed.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Haedicke, Juliane; Thomas Iftner (2013). "Detection of Immunoglobulin G against E7 of Human Papillomavirus in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer". Journal of Oncology. 18 මාර්තු 2014 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 මාර්තු 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rocha-Zavaleta L, Ambrosio JP, Mora-Garcia Mde L, Cruz-Talonia F, Hernandez-Montes J, Weiss-Steider B, Ortiz-Navarrete V, Monroy-Garcia A (2004). "Detection of antibodies against a human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 peptide that differentiate high-risk from low-risk HPV-associated low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions" (PDF). Journal of General Virology. 85 (9): 2643–2650. doi:10.1099/vir.0.80077-0. PMID 15302958. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 March 2014.

- ^ Bolhassani, Azam; Farnaz Zahedifard, Yasaman Taslimi, Mohammad Taghikhani, Bijan Nahavandian, Sima Rafati (2009). "Antibody detection against HPV16 E7 & GP96 fragments as biomarkers in cervical cancer patients" (PDF). Indian J. Med. (130): 533–541. 16 දෙසැම්බර් 2010 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 මාර්තු 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fitzgerald, Kelly (18 ජූනි 2013). "Blood Test May Detect Sexually Transmitted Throat Cancer". Medical News Today. 7 අප්රේල් 2014 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 මාර්තු 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". 10 ජනවාරි 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 මාර්තු 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Human Papillomavirus Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases". CDC.gov. 3 පෙබරවාරි 2014 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 30 ජනවාරි 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Human papillomavirus vaccines. WHO position paper" (PDF). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 84 (15): 118–31. අප්රේල් 2009. PMID 19360985. 24 දෙසැම්බර් 2010 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CDC recommends only two HPV shots for younger adolescents". CDC (ඇමෙරිකානු ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 20 ඔක්තෝබර් 2016. 23 මාර්තු 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 මාර්තු 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Simon R. M. Dobson; MD; et al. (1 මැයි 2013). "Immunogenicity of 2 Doses of HPV Vaccine in Younger Adolescents vs 3 Doses in Young Women A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 309 (17): 1793–1802. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1625. PMID 23632723. 6 ජූනි 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2 ජූනි 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER (මාර්තු 2007). "Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (Cervical Cancer Screening Among Vaccinated Females)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 56 (RR–2): 1–24 [17]. PMID 17380109. 20 මැයි 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "HPV Vaccine Information For Young Women". CDC (ඇමෙරිකානු ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 3 ජනවාරි 2017. 25 මාර්තු 2017 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 මාර්තු 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "HPV Virus: Information About Human Papillomavirus". WebMD. 8 මාර්තු 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). 12 ඔක්තෝබර් 2009 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 11 නොවැම්බර් 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Yvonne Deleré; et al. (September 2014). "The Efficacy and Duration of Vaccine Protection Against Human Papillomavirus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 111: 35–36. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2014.0584. PMC 4174682. PMID 25249360.

- ^ "FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV" (press release). 10 දෙසැම්බර් 2014. 10 ජනවාරි 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 28 පෙබරවාරි 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CDC — Condom Effectiveness — Male Latex Condoms and Sexually Transmitted Diseases". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 ඔක්තෝබර් 2009. 17 ඔක්තෝබර් 2009 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 23 ඔක්තෝබර් 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Information About What is Human Papillomavirus (HPV)?". City of Toronto Public Health Agency. September 2010. සම්ප්රවේශය 20 July 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Human papillomavirus - Public Health Agency of Canada". phac-aspc.gc.ca. 23 අගෝස්තු 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Genital HPV Infection Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 අප්රේල් 2008. 11 සැප්තැම්බර් 2012 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 නොවැම්බර් 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "HPV Vaccine Information For Young Women". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 ජූනි 2008. 26 ඔක්තෝබර් 2009 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 නොවැම්බර් 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ American Cancer Society. "What Are the Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer?". 19 February 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 21 February 2008.

- ^ "Cure for HPV". Webmd.com. 18 අගෝස්තු 2010 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 29 අගෝස්තු 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gilbert LK, Alexander L, Grosshans JF, Jolley L (2003). "Answering frequently asked questions about HPV". Sex. Transm. Dis. 30 (3): 193–4. doi:10.1097/00007435-200303000-00002. PMID 12616133. 24 දෙසැම්බර් 2011 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, October 2014" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 89: 465–492. 24 ඔක්තෝබර් 2014. PMID 25346960. 19 ඔක්තෝබර් 2015 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gavillon N, Vervaet H, Derniaux E, Terrosi P, Graesslin O, Quereux C (2010). "Papillomavirus humain (HPV) : comment ai-je attrapé ça ?". Gynécologie Obstétrique & Fertilité. 38 (3): 199–204. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2010.01.003. PMID 20189438.

- ^ Baseman JG, Koutsky LA (2005). "The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infections". J. Clin. Virol. 32 (Suppl 1): S16–24. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2004.12.008. PMID 15753008.

Overall, these DNA-based studies, combined with measurements of type-specific antibodies against HPV capsid antigens, have shown that most (>50%) sexually active women have been infected by one or more genital HPV types at some point in time [S17].

- ^ "American Social Health Association — HPV Resource Center". 18 ජූලි 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 17 අගෝස්තු 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "American Social Health Association — National HPV and Cervical Cancer Prevention Resource Center". 19 ජූනි 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 1 ජූලි 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowitz LE (පෙබරවාරි 2007). "Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States". JAMA. 297 (8): 813–9. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.813. PMID 17327523. 30 මැයි 2011 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "HPV vaccine report", STD, HIV, Planned Parenthood, http://www.plannedparenthood.org/issues-action/std-hiv/hpv-vaccine/reports/HPV-6359.htm, ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 2017-10-20, "In fact, the lifetime risk for contracting HPV is at least 50 percent for all sexually active women and men, and, it is estimated that, by the age of 50, at least 80 percent of women will have acquired sexually transmitted HPV (CDC, 2004; CDC, 2006)."

- ^ Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W (ජනවාරි–පෙබරවාරි 2004). "Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among American Youth: Incidence and Prevalence Estimates, 2000". Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 36 (1). Gutt Macher: 6–10. doi:10.1363/3600604. PMID 14982671. 4 ජූලි 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Koutsky, LA (1997). "Epidemiology of human papilomavirus infection". The American Journal of Medicine. 102: 3–8. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00177-0.

- ^ Revzina NV, Diclemente RJ (2005). "Prevalence and incidence of human papillomavirus infection in women in the USA: a systematic review". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 16 (8): 528–37. doi:10.1258/0956462054679214. PMID 16105186.

The prevalence of HPV reported in the assessed studies ranged from 14% to more than 90%.

- ^ McCullough, Marie (28 February 2007). "Cancer-virus strains rarer than first estimated". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 10 March 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2 March 2007.

- ^ Brown, David (28 පෙබරවාරි 2007) [The Washington Post, "More American Women Have HPV Than Previously Thought"]. "Study finds more women than expected have HPV". San Francisco Chronicle. 9 නොවැම්බර් 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2 මාර්තු 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help). - ^ Tanner, Lindsey (11 මාර්තු 2008). "Study Finds 1 in 4 US Teens Has a STD". Newsvine. Associated Press. 16 මාර්තු 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 17 මාර්තු 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "MMWR: Summary of Notifiable Diseases". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. CDC. 17 අගෝස්තු 2014 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 18 අගෝස්තු 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Reportable diseases සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 12 අප්රේල් 2016 at the Wayback Machine, from MedlinePlus, a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, from the National Institutes of Health. Update: 19 May 2013 by Jatin M. Vyas. Also reviewed by David Zieve.