සුඩානයේ ඉතිහාසය

ප්රාග් ඓතිහාසික සුඩානය (ක්රි.පූ. 8000ට පෙර)

[සංස්කරණය]

අෆාඩ් 23 යනු උතුරු සුඩානයේ දකුණු දිග දොංගෝල රීච් හි අෆාඩ් ප්රදේශයේ පිහිටි පුරාවිද්යාත්මක ස්ථානයකි,[1] "ප්රාග් ඓතිහාසික කඳවුරුවල (ලෝකයේ පැරණිතම එළිමහන් පැල්පතේ ධාතු) හොඳින් සංරක්ෂණය කර ඇති නටබුන් සහ විවිධ දඩයම් කිරීම සහ වසර 50,000ක් පමණ පැරණි ස්ථාන එකතු කිරීම".[2][3][4]

ක්රිපූ අටවන සහස්රය වන විට, නව ශිලා යුගයේ සංස්කෘතියකට අයත් මිනිසුන්, ශක්තිමත් මඩ ගඩොල් සහිත ගම්මානවල නිශ්චල ජීවන රටාවකට පදිංචි වී සිටි අතර, එහිදී ඔවුන් දඩයම් කිරීම සහ නයිල් ගඟේ මසුන් ඇල්ලීම සඳහා ධාන්ය එක්රැස් කිරීම සහ ගව පට්ටි පාලනය කිරීම සිදු කළහ.[5] නවශිලා යුගයේ ජනයා R12 වැනි සුසාන භූමි නිර්මාණය කළහ. ක්රිස්තු පූර්ව පස්වන සහස්රයේ දී වියළෙමින් පවතින සහරාවේ සිට සිදු වූ සංක්රමණයන් කෘෂිකර්මාන්තය සමඟ නව ශිලා යුගයේ මිනිසුන් නයිල් නිම්නයට ගෙන එන ලදී.

මෙම සංස්කෘතික හා ප්රවේණි මිශ්රණයේ ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස ජනගහණය ඊළඟ ශතවර්ෂ වලදී සමාජ ධුරාවලියක් වර්ධනය වූ අතර එය ක්රිස්තු පූර්ව 2500 දී කර්ම රාජධානිය බවට පත් විය. මානව විද්යාත්මක සහ පුරාවිද්යාත්මක පර්යේෂණවලින් පෙනී යන්නේ පූර්ව රාජවංශ යුගයේදී නූබියා සහ නාගදාන් ඉහළ ඊජිප්තුව වාර්ගික හා සංස්කෘතික වශයෙන් බොහෝ දුරට සමාන වූ අතර, ඒ අනුව, ක්රි.පූ. 3300 වන විට එකවරම පාරාවෝ රජකම් පද්ධති පරිණාමය වූ බවයි.[6]

කර්ම සංස්කෘතිය (ක්රි.පූ. 2500-1500)

[සංස්කරණය](ක්රි.පූ. 2500 - ක්රි.පූ.1550)

කර්ම සංස්කෘතිය යනු සුඩානයේ කර්මා කේන්ද්ර කරගත් මුල් ශිෂ්ටාචාරයකි. එය පුරාණ නුබියාවේ ක්රි.පූ. 2500 සිට ක්රි.පූ. 1500 දක්වා වර්ධනය විය. කර්මා සංස්කෘතිය පදනම් වූයේ නුබියා හි දකුණු ප්රදේශය හෝ "අපර් නුබියා" (වර්තමාන උතුරු සහ මධ්යම සුඩානයේ කොටස් වල) වන අතර පසුව එය උතුරු දෙසට පහළ නුබියා සහ ඊජිප්තුවේ මායිම දක්වා ව්යාප්ත විය.[7] මධ්යම ඊජිප්තු රාජධානිය සමයේ නයිල් නිම්න ප්රාන්ත කිහිපයෙන් එකක් ලෙස මෙම දේශපාලනය පැවති බව පෙනේ. ක්රි.පූ. 1700-1500 දක්වා පැවති කර්මා රාජධානියේ නවතම අවධියේදී, එය සුඩාන සායි රාජධානිය අවශෝෂණය කර ඊජිප්තුවට ප්රතිවාදී විශාල, ජනාකීර්ණ අධිරාජ්යයක් බවට පත් විය.

ඊජිප්තු නූබියා (ක්රි.පූ. 1504-1070)

[සංස්කරණය]

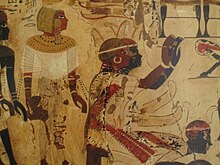

මධ්යම රාජධානියේ ක්රි.පූ. 21 වැනි සියවසේ නිර්මාතෘ වන II වන මෙන්ටුහොටෙප්, ඔහුගේ පාලන සමයේ 29 වැනි සහ 31 වැනි වසරවල කුෂ්ට එරෙහිව ව්යාපාර දියත් කළ බවට වාර්තා වේ. මෙය කුෂ් පිළිබඳ පැරණිතම ඊජිප්තු සඳහනයි; නූබියන් ප්රදේශය පැරණි රාජධානියේ වෙනත් නම් වලින් ගොස් ඇත.[8] I වන තුත්මෝස් යටතේ ඊජිප්තුව දකුණට ප්රචාරණ කිහිපයක් සිදු කළේය.

ඊජිප්තුවේ I වන තුත්මෝස් රජු කුෂ් ආක්රමණය කර එහි අගනුවර වන කර්මා විනාශ කළ විට ආරම්භ වූ නව රාජධානියේ ඊජිප්තුවරුන් කුෂ් පාලනය කළහ.[9]

මෙය අවසානයේ ඔවුන්ගේ නුබියා ඈඳා ගැනීමට හේතු විය.1504 ක්රි.පූ. ක්රි.පූ. 1500 දී පමණ නූබියාව ඊජිප්තුවේ නව රාජධානියට අන්තර්ග්රහණය කළ නමුත් කැරලි සියවස් ගණනාවක් පැවතුනි. ජයග්රහණයෙන් පසුව, කර්ම සංස්කෘතිය වැඩි වැඩියෙන් ඊජිප්තුකරණයට ලක් වූ නමුත්, කැරලි වසර 220 ක් පුරා පැවතුනි.1300 ක්රි.පූ. කෙසේ වෙතත්, නුබියා නව රාජධානියේ, ආර්ථික, දේශපාලනික සහ අධ්යාත්මික වශයෙන් ප්රධාන පළාතක් බවට පත් විය. ඇත්ත වශයෙන්ම, ප්රධාන පාරාවෝ උත්සව පැවැත්වුණේ නපට අසල ජෙබෙල් බාර්කල් හි ය.[10] පූ 16 වන සියවසේ සිට ඊජිප්තු යටත් විජිතයක් ලෙස, නුබියා ("කුෂ්") පාලනය කරනු ලැබුවේ කුෂ්හි ඊජිප්තු උපරාජයෙකු විසිනි.

අසල්වැසි කුෂ් විසින් දහඅටවන රාජවංශයේ මුල් ඊජිප්තු පාලනයට දක්වන ප්රතිරෝධය, නෙබෙට්රියා අහ්මෝස් (ක්රි.පූ. 1539-1514), I වන ඩිජෙසර්කාරා අමෙන්හොටෙප් (ක්රි.පූ. 1514-1493 පර්කකාර) යටතේ සේවය කළ ඊජිප්තු රණශූරයෙකු වූ එබානාගේ පුත් අහ්මෝස්ගේ ලේඛනවල සාක්ෂි දරයි. I වන තුත්මෝස් (ක්රි.පූ. 1493-1481). දෙවන අතරමැදි කාලපරිච්ඡේදය අවසානයේ (ක්රි.පූ. දහසයවන සියවසේ මැද) ඊජිප්තුව නිවුන් පැවැත්මේ තර්ජනවලට මුහුණ දුන්නේය - උතුරේ හයික්සෝස් සහ දකුණේ කුෂිට්වරු. ඔහුගේ සොහොන් දේවස්ථානයේ බිත්ති මත ඇති ස්වයං චරිතාපදාන සෙල්ලිපි වලින් උපුටා ගත්, ඊජිප්තුවරුන් I වන අමෙන්හොටෙප් (ක්රි.පූ. 1514-1493) යටතේ කුෂ් පරාජය කර නුබියාව යටත් කර ගැනීමට ව්යාපාර දියත් කළහ. අහ්මෝස්ගේ ලේඛනවල, කුෂිට්වරුන් දුනුවායන් ලෙස විස්තර කර ඇත, "දැන් ඔහුගේ මහරජාණෝ ආසියාවේ බෙඩොයින් මරා දැමූ පසු, ඔහු නූබියන් දුනු විනාශ කිරීම සඳහා ඉහළ නූබියාවට යාත්රා කළේය."[11] කුෂ්ගේ සොහොන් ගෙයි ලියවිලිවල නූබියන් දුනුවායන් පිළිබඳ තවත් යොමු දෙකක් අඩංගු වේ. ක්රි.පූ. 1200 වන විට ඩොංගෝලා ප්රදේශයේ ඊජිප්තු මැදිහත්වීම නොතිබුණි.

තුන්වන අතරමැදි කාලපරිච්ඡේදය අවසන් වන විට ඊජිප්තුවේ ජාත්යන්තර කීර්තිය සැලකිය යුතු ලෙස පහත වැටී තිබුණි. එහි ඓතිහාසික සහචරයින් වන කානාන්හි වැසියන්, මැද ඇසිරියානු අධිරාජ්යයට (ක්රි.පූ. 1365-1020) සහ පසුව නැවත නැගී එන නව-ඇසිරියානු අධිරාජ්යයට (ක්රි.පූ. 935-605) වැටී ඇත. ක්රිස්තු පූර්ව දහවන සියවසේ සිට ඇසිරියානුවන් නැවත වරක් උතුරු මෙසපොතේමියාවෙන් ව්යාප්ත වී ඇති අතර, මුළු ආසන්න නැගෙනහිර ප්රදේශය සහ ඇනටෝලියාව, නැගෙනහිර මධ්යධරණී මුහුද, කොකේසස් සහ මුල් යකඩ යුගය ඇතුළු විශාල අධිරාජ්යයක් යටත් කර ගත්හ.

ජොසීෆස් ෆ්ලේවියස් පවසන පරිදි, බයිබලානුකුල මෝසෙස් ඊජිප්තු හමුදාවට නායකත්වය දුන්නේ කුෂයිට් නගරයක් වන මෙරෝ වටලෑමේදී ය. වැටලීම අවසන් කිරීම සඳහා තර්බිස් කුමරිය මෝසෙස්ට (රාජ්ය තාන්ත්රික) මනාලියක් ලෙස ලබා දුන් අතර, ඒ අනුව ඊජිප්තු හමුදාව නැවත ඊජිප්තුවට පසුබැස ගියේය.[12]

කුෂ් රාජධානිය (ක්රි.පූ. 1070-ක්රි.ව. 350)

[සංස්කරණය]

කුෂ් රාජධානිය යනු නිල් නයිල් සහ සුදු නයිල් සහ අත්බරා ගඟ සහ නයිල් ගඟේ සන්ධිස්ථානයන් කේන්ද්ර කරගත් පුරාණ නූබියන් රාජ්යයකි. එය ලෝකඩ යුගයේ බිඳවැටීමෙන් සහ ඊජිප්තුවේ නව රාජධානියේ බිඳවැටීමෙන් පසුව පිහිටුවන ලදී; එය එහි මුල් අවධියේදී නපට හි කේන්ද්රගත විය.[13]

ක්රි.පූ. අටවන සියවසේදී කෂ්ට රජු ("කුෂයිට්") ඊජිප්තුව ආක්රමණය කිරීමෙන් පසුව, ඇසිරියානුවන් විසින් පරාජයට පත් කර පලවා හැරීමට පෙර සියවසකට ආසන්න කාලයක් කුෂයිට් රජවරු ඊජිප්තුවේ විසිපස්වන රාජවංශයේ පාරාවෝවරුන් ලෙස පාලනය කළහ.[14] ඔවුන්ගේ තේජසේ උච්චතම අවස්ථාව වන විට, කුෂිට්වරු දකුණු කෝර්ඩෝෆාන් ලෙස හැඳින්වෙන ප්රදේශයේ සිට සීනායි දක්වා විහිදුණු අධිරාජ්යයක් යටත් කර ගත්හ. පාරාවෝ පියේ අධිරාජ්යය ආසන්න පෙරදිගට ව්යාප්ත කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළ නමුත් ඇසිරියානු රජු II වන සර්ගොන් විසින් එය ව්යර්ථ කරන ලදී.

ක්රිස්තු පූර්ව 800 සහ ක්රිස්තු වර්ෂ 100 අතර නූබියන් පිරමිඩ ඉදිකරන ලද අතර, ඒවා අතර එල්-කුරුරු, කෂ්තා, පියේ, ටන්ටමනි, ෂබකා, ගෙබෙල් බාර්කල් පිරමිඩ, මෙරෝහි පිරමිඩ (බෙගරාවියා), සෙඩිංගා පිරමිඩ සහ ප්රිමිඩ ලෙස නම් කළ හැක.[15]

කුෂ් රාජධානිය ඊශ්රායෙලිතයන් ඇසිරියානුවන්ගේ උදහසින් ගලවා ගත් බව බයිබලයේ සඳහන් වේ, නමුත් වටලන්නන් අතර ඇති වූ රෝග නගරය අල්ලා ගැනීමට අපොහොසත් වීමට එක් හේතුවක් විය හැකිය.[16] යුද්ධය පාරාවෝ තහර්කා සහ ඇසිරියානු රජු සෙනකෙරිබ් අතර සිදුවූයේ බටහිර ඉතිහාසයේ තීරනාත්මක සිදුවීමක් වූ අතර, නුබියානුවන් පරාජයට පත් විය. ඇසිරියාවට ආසන්න නැගෙනහිර. සෙනකෙරිබ්ගේ අනුප්රාප්තිකයා වූ එසාර්හැඩොන් තව දුරටත් ගොස් ලෙවන්ට්හි තම පාලනය තහවුරු කර ගැනීම සඳහා ඊජිප්තුව ආක්රමණය කළේය. ටහර්කා පහළ ඊජිප්තුවෙන් නෙරපා හැරීමට ඔහු සමත් වූ බැවින් මෙය සාර්ථක විය. ටහර්කා නැවතත් ඉහළ ඊජිප්තුවට සහ නූබියාවට පලා ගිය අතර එහිදී ඔහු වසර දෙකකට පසු මිය ගියේය. පහළ ඊජිප්තුව ඇසිරියානු යටත් විජිත පාලනයට යටත් වූ නමුත් අසිරියානුවන්ට එරෙහිව අසාර්ථක ලෙස කැරලි ගැසූ අතර එය අකීකරු විය. ඉන්පසුව, ටහර්කාගේ අනුප්රාප්තිකයා වූ ටැන්ටමනි රජු, අලුතින් යලි පිහිටුවන ලද ඇසිරියානු යටත්වැසියෙකු වන I වන නෙචෝ වෙතින් පහළ ඊජිප්තුව නැවත ලබා ගැනීමට අවසාන අධිෂ්ඨානශීලී උත්සාහයක් ගත්තේය. එම ක්රියාවලියේදී නෙචෝ මරා දැමූ මෙම්ෆිස් නැවත අත්පත් කර ගැනීමට සහ නයිල් ඩෙල්ටාවේ නගර වටලෑමට ඔහු සමත් විය. එසර්හඩ්ඩොන් අනුප්රාප්තිකයා වූ අෂුර්බනිපල් නැවත පාලනය ලබා ගැනීම සඳහා විශාල හමුදාවක් ඊජිප්තුවට යැවීය. ඔහු මෙම්ෆිස් අසලදී ටැන්ටමනීව පරාජය කළ අතර, ඔහු පසුපස හඹා ගොස් තීබ්ස් නෙරපා හැරියේය. මෙම සිදුවීම්වලින් පසු ඇසිරියානුවන් වහාම ඉහළ ඊජිප්තුවෙන් පිටව ගියද, දුර්වල වූ නමුත්, තීබ්ස් දශකයකටත් අඩු කාලයකට පසුව නෙචෝ ගේ පුත් I වන ප්සම්තික් වෙත සාමකාමීව යටත් විය. මෙය නූබියන් අධිරාජ්යයේ පුනර්ජීවනයක් පිළිබඳ සියලු බලාපොරොත්තු අවසන් කළ අතර එය නපාටා කේන්ද්ර කර ගත් කුඩා රාජධානියක ස්වරූපයෙන් දිගටම පැවතුනි. ඊජිප්තු ආ විසින් නගරය වටලා ඇත. ක්රිපූ 590, සහ ක්රි.පූ. 3 වැනි සියවසේ අගභාගයේදී, කුෂයිට්වරු මෙරෝයි හි නැවත පදිංචි වූහ.[14][17][18]

මධ්යකාලීන ක්රිස්තියානි නූබියන් රාජධානි (ක්රි.ව. 350–1500)

[සංස්කරණය]

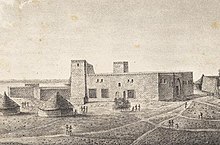

පස්වන සියවස ආරම්භයේදී බ්ලෙම්මිස් ඉහළ ඊජිප්තුවේ සහ පහළ නුබියා හි කෙටි කාලීන රාජ්යයක් පිහිටුවන ලදී, බොහෝ විට තල්මිස් (කලාබ්ෂා) වටා කේන්ද්රගත විය, නමුත් 450 ට පෙර ඔවුන් දැනටමත් නොබැටියන් විසින් නයිල් නිම්නයෙන් පලවා හරින ලදී. අන්තිමේදී ඔවුන් විසින්ම නොබැටියා රාජ්යයක් පිහිටුවීය.[20] හයවන සියවස වන විට නූබියානු රාජධානි තුනක් විය: උතුරේ නොබැටියා, එහි අගනුවර වූයේ පචෝරස් (ෆරාස්); මධ්යම රාජධානිය වන මකුරියා, නූතන ඩොංගෝලාවට දකුණින් කිලෝමීටර 13 (සැතපුම් 8) පමණ දුරින් තුන්ගුල් (පැරණි ඩොංගෝලා) හි කේන්ද්රගත විය; සහ පැරණි කුෂිටික් රාජධානියේ හදවතෙහි පිහිටි ඇලෝඩියා, එහි අගනුවර වූයේ සෝබා (දැන් නූතන කාර්ටූම්හි උප නගරයකි) ය.[21] තවමත් හයවන සියවසේදී ඔවුන් ක්රිස්තියානි ආගමට හැරුණි.[22] හත්වන සියවසේදී, බොහෝ විට 628 සහ 642 අතර යම් අවස්ථාවක, නොබැටියා මකුරියාවට සංස්ථාගත විය.[23]

639 සිට 641 දක්වා කාලය තුළ රෂිඩුන් කැලිෆේට්හි මුස්ලිම් අරාබිවරුන් බයිසැන්තියානු ඊජිප්තුව යටත් කර ගත්හ. 641 හෝ 642 දී සහ නැවතත් 652 දී ඔවුන් නුබියාව ආක්රමණය කළ නමුත් පලවා හරින ලද අතර, ඉස්ලාමීය ව්යාප්තියේ දී අරාබිවරුන් පරාජය කිරීමට සමත් වූ කිහිප දෙනාගෙන් නුබියානුවන් ද එක් විය. ඉන්පසුව මකුරියානු රජු සහ අරාබිවරුන් සුවිශේෂී ආක්රමණශීලී නොවන ගිවිසුමකට එකඟ වූ අතර එයට වාර්ෂික තෑගි හුවමාරුවක් ද ඇතුළත් වූ අතර එමඟින් මකුරියාගේ ස්වාධීනත්වය පිළිගනු ලැබීය.[24] අරාබිවරුන් නුබියාව යටත් කර ගැනීමට අපොහොසත් වූ අතර, ඔවුන් නයිල් ගඟට නැගෙනහිරින් පදිංචි වීමට පටන් ගත් අතර, අවසානයේදී ඔවුන් වරාය නගර කිහිපයක්[25] ආරම්භ කර ප්රාදේශීය බෙජා සමඟ විවාහ විය.[26]

අටවන සියවසේ මැද භාගයේ සිට එකොළොස්වන සියවසේ මැද භාගයේ සිට ක්රිස්ටියන් නුබියාවේ දේශපාලන බලය සහ සංස්කෘතික දියුණුව උච්චස්ථානයට පත් විය.[27] 747 දී මකුරියා ඊජිප්තුව ආක්රමණය කළ අතර, එය මේ වන විට පරිහානියට පත් වූ උමයියාඩ්වරුන්ට අයත් වූ අතර,[28] එය නැවතත් 960 ගණන්වල මුල් භාගයේදී, අක්මිම් දක්වා උතුරට තල්ලු වූ විට එය නැවත සිදු කළේය.[29] මකුරියා ඇලෝඩියා සමඟ සමීප රාජවංශික සබඳතා පවත්වාගෙන ගිය අතර, සමහර විට රාජධානි දෙක තාවකාලිකව එක් රාජ්යයක් බවට ඒකාබද්ධ කිරීමට හේතු විය.[30] මධ්යතන යුගයේ නූබියන්ස් ගේ සංස්කෘතිය "ඇෆ්රෝ-බයිසැන්ටයින්" ලෙස විස්තර කර ඇත,[31] නමුත් අරාබි සංස්කෘතියේ බලපෑම වැඩි විය.[32] හයවන සහ හත්වන සියවස්වල බයිසැන්තියානු නිලධරය මත පදනම් වූ,[33] රාජ්ය සංවිධානය අතිශයින් මධ්යගත විය.[34] කුඹල් සිතුවම්[35] සහ විශේෂයෙන්ම බිත්ති සිතුවම් ආකාරයෙන් කලාව දියුණු විය.[36] නූබියන්වරු ඔවුන්ගේ භාෂාව වන පැරණි නොබියින් සඳහා හෝඩියක් සකස් කර ගත් අතර, එය කොප්ටික් හෝඩිය මත පදනම් වූ අතර ග්රීක, කොප්ටික් සහ අරාබි යන භාෂා ද භාවිතා කළහ.[37] කාන්තාවන් උසස් සමාජ තත්වයක් භුක්ති වින්දා: ඔවුන්ට අධ්යාපනයට ප්රවේශය, ඉඩම් අයිති කර ගැනීමට, මිලදී ගැනීමට සහ විකිණීමට හැකි වූ අතර බොහෝ විට ඔවුන්ගේ ධනය පල්ලි සහ පල්ලි සිතුවම් පරිත්යාග කිරීමට භාවිතා කළහ.[38] රාජකීය අනුප්රාප්තිය පවා මාතෘ පාරම්පරික විය, රජුගේ සහෝදරියගේ පුත්රයා නියම උරුමක්කාරයා විය.[39]

11වන/12වන සියවසේ අගභාගයේ සිට, මකුරියාවේ අගනුවර වන ඩොංගෝලාව පරිහානියට පත් වූ අතර, 12වන සියවසේදීද ඇලෝඩියා අගනුවර පිරිහීමට ලක් විය.[40] 14 වන සහ 15 වන ශතවර්ෂ වලදී බෙඩොයින් ගෝත්රිකයන් සුඩානයේ වැඩි ප්රමාණයක් අත්පත් කර ගත් අතර,[41] බුටානා, ගෙසිරා, කෝර්ඩෝෆාන් සහ ඩාර්ෆූර් වෙත සංක්රමණය විය.[42] 1365 දී සිවිල් යුද්ධයක් හේතුවෙන් මකුරියානු අධිකරණයට පහළ නුබියාවේ ගෙබෙල් ඇඩා වෙත පලා යාමට සිදු වූ අතර ඩොන්ගෝලාව විනාශ කර අරාබිවරුන්ට භාර දෙන ලදී. ඉන්පසුව මකුරියාව දිගටම පැවතුනේ කුඩා රාජධානියක් ලෙස පමණි.[43] ජොයෙල් (1463-1484) රජුගේ සමෘද්ධිමත්[44] පාලන සමයෙන් පසුව මකුරියා බිඳ වැටුණි. දකුණු සුඩානයේ සිට සුආකින් වරාය නගරය දක්වා වෙරළබඩ ප්රදේශ පහළොස්වන සියවසේදී ආඩාල් සුල්තාන්වරයා විසින් පාලනය කරන ලදී.[45][46]දකුණින්, ඇලෝඩියා රාජධානිය ගෝත්රික නායක අබ්දල්ලා ජම්මා විසින් අණ දෙන ලද අරාබිවරුන්ට හෝ දකුණෙන් ආරම්භ වූ අප්රිකානු ජනතාවක් වන ෆන්ජ් අතට පත්විය.[47] කාල නිර්ණයන් හිජ්රාට පසු 9 වන සියවසේ සිට (ආ. 1396-1494),[48] 15 වන සියවසේ අගභාගය,[49] 1504[50] සිට 1509[51] දක්වා පරාසයක පවතී. 1685 දක්වා පැවති ෆසුග්ලි රාජධානියේ ස්වරූපයෙන් ඇලෝඩියන් රම්ප් රාජ්යයක් පැවතිය හැකිය.[52]

සෙන්නාර් සහ ඩාර්ෆුර් ඉස්ලාමීය රාජධානි (ක්රි.ව. 1500-1821)

[සංස්කරණය]

1504 දී ෆන්ජ් සෙන්නාර් රාජධානිය ආරම්භ කළ බවට වාර්තා වන අතර, අබ්දුල්ලා ජම්මාගේ රාජධානිය එහි සංස්ථාගත කරන ලදී.[54] 1523 වන විට, යුදෙව් සංචාරකයෙකු වූ ඩේවිඩ් රූබේනි සුඩානයට පැමිණි විට, ෆන්ජ් රාජ්යය දැනටමත් උතුරට ඩොංගෝලා දක්වා විහිදේ.[55] මේ අතර, 15 සහ 16 වැනි සියවස්වල[56] එහි පදිංචි වූ සූෆි ශුද්ධ මිනිසුන් විසින් නයිල් ගඟේ ඉස්ලාමය දේශනා කිරීමට පටන් ගත් අතර ඩේවිඩ් රූබේනිගේ සංචාරයෙන් මිථ්යාදෘෂ්ටික හෝ නාමික කිතුනුවකු වූ අමරා ඩන්කාස් රජු මුස්ලිම් බවට වාර්තා විය[57] කෙසේ වෙතත්, ෆන්ජ් දිව්ය රජකම හෝ මත්පැන් පානය වැනි ඉස්ලාම් නොවන සිරිත් විරිත් 18 වන සියවස දක්වාම රඳවා ගනු ඇත.[58] සුඩාන ජන ඉස්ලාම් ක්රිස්තියානි සම්ප්රදායන්ගෙන් පැන නැඟුණු බොහෝ චාරිත්ර මෑත අතීතය දක්වාම ආරක්ෂා කර ගෙන ඇත.[59]

වැඩි කල් නොගොස් ෆන්ජ් සුආකින් ආ අල්ලාගෙන සිටි ඔටෝමන්වරුන් සමඟ ගැටුමකට පැමිණියේය.1526[60] අවසානයේ නයිල් ගඟ දිගේ දකුණට තල්ලු වී 1583/1584 දී තුන්වන නයිල් ඇසේ සුද ඉවත් කිරීමේ ප්රදේශයට ළඟා විය. 1585 දී ෆන්ජ් විසින් ඩොන්ගෝලාව අල්ලා ගැනීමට ඔටෝමාන් උත්සාහයක් පසුකාලීනව පලවා හරින ලදී.[61] ඉන්පසුව, තුන්වන ඇසේ සුදට දකුණින් පිහිටි හැනික්, ප්රාන්ත දෙක අතර මායිම සලකුණු කරයි.[62] ඔටෝමාන් ආක්රමණයෙන් පසු උතුරු නූබියාවේ සුළු රජෙකු වූ අජිබ් පැහැර ගැනීමට උත්සාහ දැරීය. 1611/1612 දී ෆන්ජ් විසින් ඔහුව මරා දැමූ අතර, ඔහුගේ අනුප්රාප්තිකයන් වන අබ්දල්ලාබ්ට සැලකිය යුතු ස්වයං පාලනයක් සහිතව නිල් සහ සුදු නයිල්ස් සමුහයට උතුරින් ඇති සියල්ල පාලනය කිරීමට අවසර දෙන ලදී.[63]

17 වන ශතවර්ෂයේදී ෆන්ජ් රාජ්යය එහි පුළුල්ම ප්රමාණයට ළඟා විය,[64] නමුත් ඊළඟ සියවසේදී එය පිරිහීමට පටන් ගත්තේය.[65] 1718 දී සිදු වූ කුමන්ත්රණයක් රාජවංශික වෙනසක් ගෙන ආ අතර,[66] 1761-1762[67] දී සිදු වූ තවත් කුමන්ත්රණයක් හමාජ් ප්රාන්තයේ ප්රතිඵලයක් විය,[68] එහිදී හමාජ් (ඉතියෝපියානු දේශසීමාවේ ජනතාවක්) ඵලදායී ලෙස පාලනය කළ අතර ෆන්ජ් සුල්තාන්වරු ඔවුන්ගේ රූකඩ විය.[69] ඉන් ටික කලකට පසු සුල්තාන් රාජ්යය ඛණ්ඩනය වීමට පටන් ගත්තේය.[70]

1718 කුමන්ත්රණය වඩාත් සාම්ප්රදායික ඉස්ලාම් ආගමක් අනුගමනය කිරීමේ ප්රතිපත්තියක් ආරම්භ කළ අතර එය රාජ්යයේ අරාබිකරණය ප්රවර්ධනය කළේය.[71] ඔවුන්ගේ අරාබි යටත්වැසියන් කෙරෙහි ඔවුන්ගේ පාලනය නීත්යානුකූල කිරීම සඳහා ෆන්ජ්වරු උමයියාද් පරම්පරාවක් ප්රචාරණය කිරීමට පටන් ගත්හ.[72] නිල් සහ සුදු නයිල්ස් සමුහයට උතුරින්, අල් ඩබ්බා දක්වා පහළින්, නූබියන්වරු අරාබි ජාලින් ගෝත්රික අනන්යතාවය අනුගමනය කළහ.[73] 19 වැනි සියවස දක්වා මධ්යම ගංගාවේ සුඩානයේ[74][75][76] සහ බොහෝ කොර්ඩෝෆාන්හි ප්රමුඛ භාෂාව බවට පත්වීමට අරාබි සමත් විය.[77]

නයිල් ගඟට බටහිර දෙසින්, ඩාර්ෆූර්හි, ඉස්ලාමීය යුගයේදී මුලින්ම තුන්ජුර් රාජධානියේ නැගීම දක්නට ලැබුණි, එය 15 වැනි සියවසේ[78] පැරණි ඩජු රාජධානිය ප්රතිස්ථාපනය කර බටහිරින් වඩයි දක්වා ව්යාප්ත විය.[79] තුන්ජුර් ජනයා අරාබිකරණය වූ බර්බර්වරුන් විය හැකි අතර, ඔවුන්ගේ පාලක ප්රභූව අවම වශයෙන් මුස්ලිම්වරුන් විය හැකිය.[80] 17 වන ශතවර්ෂයේදී තුන්ජුර්වරුන් ෆර් කීරා සුල්තාන්වරයා විසින් බලයෙන් පලවා හරින ලදී.[79] සුලෙයිමාන් සොලොන්ග් (1660-1680) ගේ පාලන සමයේ සිට නාමික වශයෙන් මුස්ලිම් වූ කීරා ප්රාන්තය,[81] මුලින් උතුරු ජෙබෙල් මාරා හි කුඩා රාජධානියක් වූ අතර,[82] 18 වැනි සියවසේ මුල් භාගයේදී බටහිර හා උතුරු දෙසට ව්යාප්ත විය.[83] සහ නැඟෙනහිර දෙසට මුහම්මද් ටයිරාබ් (1751-1786) ගේ පාලනය යටතේ,[84] උච්චතම අවස්ථාව 1785 දී කෝඩෝෆාන් යටත් කර ගැනීම.[85] මෙම අධිරාජ්යයේ උච්චතම අවස්ථාව, දැන් දළ වශයෙන් වර්තමාන නයිජීරියාවේ විශාලත්වය,[85] 1821 දක්වා පවතිනු ඇත.[84]

තුර්කිය සහ මහඩිස්ට් සුඩානය (ක්රි.ව. 1821-1899)

[සංස්කරණය]

1821 දී ඊජිප්තුවේ ඔටෝමාන් පාලකයා වූ ඊජිප්තුවේ මුහම්මද් අලි උතුරු සුඩානය ආක්රමණය කර යටත් කර ගත්තේය. ඔටෝමාන් අධිරාජ්යය යටතේ තාක්ෂණිකව ඊජිප්තුවේ වාලි වුවද, මුහම්මද් අලි තමාව හැඩගස්වා ගත්තේ ප්රායෝගිකව ස්වාධීන ඊජිප්තුවේ කේඩිව් ලෙසය. සුඩානය ඔහුගේ වසම්වලට එකතු කිරීමට උත්සාහ කරමින්, ඔහු තම තුන්වන පුත් ඉස්මයිල් (පසුව සඳහන් කළ ඉස්මායිල් පාෂා සමඟ පටලවා නොගත යුතුය) රට යටත් කර ගැනීමට යවා, පසුව එය ඊජිප්තුවට ඇතුළත් කළේය. කෝඩෝෆාන් හි ෂයිකියා සහ ඩාර්ෆුර් සුල්තාන්වරයා හැරුණු විට, ඔහු ප්රතිරෝධයකින් තොරව හමු විය. ඊබ්රාහිම් පාෂාගේ පුත් ඉස්මායිල් විසින් ඊජිප්තු යටත් කර ගැනීමේ ප්රතිපත්තිය පුළුල් කර තීව්ර කරන ලදී, ඔහුගේ පාලනය යටතේ නූතන සුඩානයේ ඉතිරි බොහෝ ප්රදේශ යටත් කර ගන්නා ලදී.

ඊජිප්තු බලධාරීන් සුඩාන යටිතල පහසුකම් (ප්රධාන වශයෙන් උතුරේ) විශේෂයෙන් වාරිමාර්ග සහ කපු නිෂ්පාදනය සම්බන්ධයෙන් සැලකිය යුතු දියුණුවක් ඇති කළේය. 1879 දී මහා බලවතුන් ඉස්මයිල් ඉවත් කිරීමට බල කළ අතර ඔහු වෙනුවට ඔහුගේ පුත් ටෙව්ෆික් පාෂා පිහිටුවන ලදී. ටෙව්ෆික් ගේ දූෂණය සහ වැරදි කළමනාකරණය ඛෙඩිව් ගේ පැවැත්මට තර්ජනයක් වූ 'උරාබි කැරැල්ලට හේතු විය. පසුව 1882 දී ඊජිප්තුව අත්පත් කරගත් බ්රිතාන්යයන්ට උපකාර ඉල්ලා ටෙව්ෆික් ආයාචනා කළේය. සුඩානය කෙඩිවියල් රජය අතට පත් වූ අතර, එහි නිලධාරීන්ගේ වැරදි කළමනාකරණය සහ දූෂණය නිසා විය.[86][87]

කෙදිවිල් පාලන සමයේදී බොහෝ ක්රියාකාරකම් සඳහා පනවා තිබූ දැඩි බදු හේතුවෙන් විසම්මුතිය පැතිර ගොස් තිබුණි. වාරි ළිං සහ ගොවිබිම් මත බදු පැනවීම ඉතා ඉහළ මට්ටමක පැවතියේ බොහෝ ගොවීන් තම ගොවිපල සහ පශු සම්පත් අත්හැර දැමූහ. 1870 ගණන් වලදී, වහල් වෙළඳාමට එරෙහි යුරෝපීය මුලපිරීම් උතුරු සුඩානයේ ආර්ථිකයට අහිතකර බලපෑමක් ඇති කළ අතර, එය මහඩිස්ට් බලවේගවල නැගීම වේගවත් කළේය.[88] මුහම්මද් අහමඩ් ඉබ්න් අබ්දුල්ලාහ්, මහ්දි (මඟපෙන්වූ තැනැත්තා), අන්සාර්වරුන්ට (ඔහුගේ අනුගාමිකයින්ට) සහ ඔහුට යටත් වූ අයට ඉස්ලාමය පිළිගැනීම හෝ මරා දැමීම අතර තේරීමක් ඉදිරිපත් කළේය. මහදියා (මහඩිස්ට් තන්ත්රය) සම්ප්රදායික ෂරියා ඉස්ලාමීය නීති පැනවීය. 1881 අගෝස්තු 12 වන දින, අබා දූපතේ සිදුවීමක් සිදු වූ අතර, එය මහඩිස්ට් යුද්ධය බවට පත් විය.

1881 ජූනි මාසයේදී මහදියා ප්රකාශ කිරීමේ සිට 1885 ජනවාරි මාසයේදී කාර්ටූම් වැටීම දක්වා, මුහම්මද් අහමඩ් තුර්කිය ලෙස හැඳින්වෙන සුඩානයේ ටර්කෝ-ඊජිප්තු රජයට එරෙහිව සාර්ථක හමුදා මෙහෙයුමක් මෙහෙයවීය. මුහම්මද් අහමඩ් 1885 ජුනි 22 දින මිය ගියේය, කාර්ටූම් යටත් කර ගැනීමෙන් මාස හයකට පසුවය. ඔහුගේ නියෝජිතයන් අතර බල අරගලයකින් පසු, අබ්දුල්ලාහි ඉබ්න් මුහම්මද්, මූලික වශයෙන් බටහිර සුඩානයේ බග්ගරාගේ උපකාරයෙන්, අනෙක් අයගේ විරුද්ධත්වය මැඩගෙන, මහදියාගේ අභියෝග නොකළ නායකයා ලෙස මතු විය. ඔහුගේ බලය තහවුරු කර ගැනීමෙන් පසු, අබ්දල්ලාහි ඉබ්න් මුහම්මද් මහ්දිගේ කලීෆා (අනුප්රාප්තික) යන පදවි නාමය ලබාගෙන, පරිපාලනයක් ස්ථාපිත කර, අන්සාර් (සාමාන්යයෙන් බග්ගරා වූ) එමීර්වරුන් ලෙස එක් එක් පළාත් කිහිපයකම පත් කළේය.

මහදියා යුගයේ බොහෝ කාලයක් පුරා කලාපීය සබඳතා නොසන්සුන්ව පැවතියේ, බොහෝ දුරට කලීෆාගේ ම්ලේච්ඡ ක්රම නිසා රට පුරා ඔහුගේ පාලනය ව්යාප්ත කිරීම හේතුවෙනි. 1887 දී, මිනිසුන් 60,000 කින් යුත් අන්සාර් හමුදාවක් ඉතියෝපියාව ආක්රමණය කළ අතර එය ගොන්ඩාර් දක්වා විනිවිද ගියේය. 1889 මාර්තු මාසයේදී ඉතියෝපියාවේ IV වන යොහානස් රජු මෙටෙම්මා වෙත ගමන් කළේය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, යොහානස් සටනින් වැටීමෙන් පසුව, ඉතියෝපියානු හමුදා ඉවත් විය. කලීෆාගේ ජෙනරාල් අබ්දුර්-රහ්මාන් අන්-නුජුමි 1889 දී ඊජිප්තුව ආක්රමණය කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළ නමුත් බ්රිතාන්ය ප්රමුඛ ඊජිප්තු හමුදා තුෂ්කාහිදී අන්සාර්වරුන් පරාජය කළහ. ඊජිප්තු ආක්රමණයේ අසාර්ථකත්වය අන්සාර්වරුන්ගේ අනභිභවනීය බවේ අක්ෂර වින්යාසය බිඳ දැමීය. බෙල්ජියම්වරු මහඩිගේ මිනිසුන් සමකය යටත් කර ගැනීම වැළැක්වූ අතර, 1893 දී, ඉතාලියානුවන් ඇගෝඩාට් (එරිත්රියාවේ) හි අන්සාර් ප්රහාරයක් මැඩපැවැත්වූ අතර අන්සාර්වරුන්ට ඉතියෝපියාවෙන් ඉවත් වීමට බල කළහ.

1890 ගණන් වලදී, බ්රිතාන්යයන් සුඩානය මත ඔවුන්ගේ පාලනය යළි ස්ථාපිත කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළ අතර, නැවත වරක් නිල වශයෙන් ඊජිප්තු කේඩීව් නමින්, නමුත් ඇත්ත වශයෙන්ම රට බ්රිතාන්ය යටත් විජිතයක් ලෙස සලකන ලදී. 1890 ගණන්වල මුල් භාගය වන විට, බ්රිතාන්ය, ප්රංශ සහ බෙල්ජියම් හිමිකම් නයිල් ගංගාවේදී අභිසාරී විය. බ්රිතාන්යය බිය වූයේ සුඩානයේ අස්ථාවරත්වයේ ප්රයෝජනය අනෙකුත් බලවතුන් විසින් කලින් ඊජිප්තුවට ඈඳාගත් භූමි ප්රදේශ අත්පත් කරගනු ඇතැයි කියාය. මෙම දේශපාලන සලකා බැලීම්වලට අමතරව, අස්වාන් හි සැලසුම් කළ වාරි වේල්ලක් ආරක්ෂා කිරීම සඳහා නයිල් ගඟේ පාලනය ස්ථාපිත කිරීමට බ්රිතාන්යයට අවශ්ය විය. හර්බට් කිචනර් 1896 සිට 1898 දක්වා මහඩිස්ට් සුඩානයට එරෙහිව හමුදා මෙහෙයුම් මෙහෙයවීය. 1898 සැප්තැම්බර් 2 වන දින ඔම්දුර්මන් සටනේදී කිචනර්ගේ ව්යාපාර තීරණාත්මක ජයග්රහණයකින් අවසන් විය. වසරකට පසුව, උම් දිවායිකරත් සටනින් 1899 නොවැම්බර් 25 වන දින අබ්දාලාහි මරණයට පත් විය. ඉබ්න් මුහම්මද්, පසුව මහඩිස්ට් යුද්ධය අවසන් කිරීම සිදු විය.

ඇන්ග්ලෝ-ඊජිප්තු සුඩානය (ක්රි.ව. 1899-1956)

[සංස්කරණය]

1899 දී, බ්රිතාන්යය සහ ඊජිප්තුව ගිවිසුමකට එළැඹුණු අතර, ඒ යටතේ සුඩානය බ්රිතාන්ය අනුමැතිය ඇතිව ඊජිප්තුව විසින් පත් කරන ලද අග්රාණ්ඩුකාරවරයෙකු විසින් පාලනය කරන ලදී.[89] යථාර්ථය නම්, සුඩානය ඔටුන්න හිමි ජනපදයක් ලෙස ඵලදායී ලෙස පරිපාලනය කරන ලදී. මුහම්මද් අලි පාෂා යටතේ ඊජිප්තු නායකත්වය යටතේ නයිල් නිම්නය එක්සේසත් කිරීමේ ක්රියාවලිය ආපසු හැරවීමට බ්රිතාන්යයන් උනන්දු වූ අතර දෙරට තවදුරටත් එක්සත් කිරීම අරමුණු කරගත් සියලු උත්සාහයන් ව්යර්ථ කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළහ.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

සීමා නිර්ණය යටතේ, අබිසීනියාව සමඟ සුඩානයේ දේශසීමාව නීතියේ සීමාවන් උල්ලංඝනය කරමින් වහලුන් වෙළඳාම් කරන ගෝත්රිකයන් වැටලීම මගින් තරඟ කරන ලදී. 1905 දී ප්රාදේශීය නායක සුල්තාන් යැම්බියෝ, අවසානය දක්වා අකමැත්තෙන්, කෝඩෝෆාන් ප්රදේශය අත්පත් කරගෙන සිටි බ්රිතාන්ය හමුදා සමඟ අරගලය අතහැර දමා අවසානයේ අවනීතිය අවසන් කළේය. බ්රිතාන්යය විසින් ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලද අණපනත් මගින් බදු අයකිරීමේ ක්රමයක් පැනවීය. මෙය කලීෆා විසින් සකස් කරන ලද පූර්වාදර්ශය අනුගමනය කරන ලදී. ප්රධාන බදු හඳුනාගෙන ඇත. මෙම බදු ඉඩම්, ගව පට්ටි සහ රට ඉඳි මත විය.[90] ඊජිප්තුවේ සහ සුඩානයේ තනි ස්වාධීන සංගමයක් පිළිගැනීමට බ්රිතාන්යයට බල කිරීමට ඊජිප්තු ජාතිකවාදී නායකයින් අධිෂ්ඨාන කර ගනිමින්, සුඩානයේ අඛණ්ඩ බ්රිතාන්ය පරිපාලනය වඩ වඩාත් දැඩි ජාතිකවාදී පසුබෑමක් ඇති කළේය. 1914 දී ඔටෝමාන් පාලනය විධිමත් ලෙස අවසන් කිරීමත් සමඟ, නව හමුදා ආණ්ඩුකාරවරයා ලෙස සුඩානය අල්ලා ගැනීම සඳහා ශ්රීමත් රෙජිනෝල්ඩ් වින්ගේට් එම දෙසැම්බරයේ යවන ලදී. හුසේන් කමෙල් ඊජිප්තුවේ සහ සුඩානයේ සුල්තාන්වරයා ලෙස ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලදී, ඔහුගේ සහෝදරයා සහ අනුප්රාප්තිකයා වූ I වන ෆුවාඩ්. ඊජිප්තුවේ සුල්තාන් රාජ්යය ඊජිප්තු රාජධානිය සහ සුඩානය ලෙස නැවත නම් කරන විට පවා ඔවුන් එක ඊජිප්තු-සුඩාන රාජ්යයක් සඳහා ඔවුන්ගේ අවධාරනය දිගටම කරගෙන ගිය නමුත් එය 1927 දී ඔහු මිය යන තෙක්ම අභිලාෂයන් ගැන කලකිරී සිටි සාද් සාග්ලූල් විය.[91]

1924 සිට 1956 නිදහස දක්වා, බ්රිතාන්යයන් සුඩානය මූලික වශයෙන් වෙනම ප්රදේශ දෙකක් ලෙස පවත්වාගෙන යාමේ ප්රතිපත්තියක් අනුගමනය කළහ. උතුර සහ දකුණ. කයිරෝවේ දී ඇන්ග්ලෝ-ඊජිප්තු සුඩානයේ ආණ්ඩුකාර ජනරාල්වරයෙකු ඝාතනය කිරීම හේතුකාරකය විය; එය යටත් විජිත බලවේගවලින් අලුතින් තේරී පත් වූ වෆ්ඩ් ආන්ඩුවට ඉල්ලීම් ගෙන ආවේය. කාර්ටූම් හි බලඇණි දෙකක ස්ථිර පිහිටුවීමක් රජය යටතේ ක්රියා කරන සුඩාන ආරක්ෂක බලකාය ලෙස නම් කරන ලද අතර, කලින් ඊජිප්තු හමුදා සොල්දාදුවන්ගේ බලකොටුව වෙනුවට, වල්වාල් සිද්ධියෙන් පසුව ක්රියාත්මක විය.[92] වෆ්ඩිස්ට් පාර්ලිමේන්තු බහුතරය ලන්ඩනයේ ඔස්ටින් චේම්බර්ලයින් සමඟ සර්වාට් පාෂාගේ නවාතැන් සැලැස්ම ප්රතික්ෂේප කර ඇත; එහෙත් කයිරෝවට තවමත් මුදල් අවශ්ය විය. සුඩාන රජයේ ආදායම 1928 දී පවුම් මිලියන 6.6ක උපරිමයකට ළඟා වී ඇති අතර, ඉන් පසුව වෆ්ඩිස්ට් බාධා කිරීම් සහ ලන්ඩනයේ සෝමාලිලන්තයෙන් ඉතාලි දේශසීමා ආක්රමණය හේතුවෙන් මහා අවපාතය අතරතුර වියදම් අඩු කිරීමට තීරණය කළේය. බ්රිතාන්යයේ සිට සෑම දෙයක්ම පාහේ ආනයනය කිරීමේ අවශ්යතාවය නිසා කපු සහ ගම් අපනයනය වාමන විය.[93]

1936 ජූලි මාසයේදී ලිබරල් ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථා නායක මුහම්මද් මහමුද්, "ඇන්ග්ලෝ-ඊජිප්තු සබඳතාවල නව අදියරක ආරම්භය" වන ඇන්ග්ලෝ-ඊජිප්තු ගිවිසුම අත්සන් කිරීම සඳහා වෆ්ඩ් නියෝජිතයන් ලන්ඩනයට ගෙන්වා ගැනීමට පෙළඹවූ බව ඇන්තනි ඊඩන් ලිවීය.[94] ඇළ කලාපය ආරක්ෂා කිරීම සඳහා බ්රිතාන්ය හමුදාවට සුඩානයට ආපසු යාමට අවසර ලැබුණි. ඔවුන්ට පුහුණු පහසුකම් සොයා ගැනීමට හැකි වූ අතර RAF හට ඊජිප්තු භූමිය හරහා පියාසර කිරීමට නිදහස තිබුණි. කෙසේ වෙතත්, එය සුඩානයේ ගැටලුව විසඳුවේ නැත: සුඩාන බුද්ධිමතුන් ජර්මනියේ නියෝජිතයන් සමඟ කුමන්ත්රණය කරමින් මහානගර පාලනයට නැවත පැමිණීම සඳහා උද්ඝෝෂණ කළහ.[95]

ඉතාලි ෆැසිස්ට් නායක බෙනිටෝ මුසෝලිනි පැහැදිලිවම කියා සිටියේ තමාට ඊජිප්තුව සහ සුඩානය යටත් කර නොගෙන අබිසීනියාව ආක්රමණය කළ නොහැකි බවයි. ඔවුන් අදහස් කළේ ඉතාලි ලිබියාව ඉතාලි නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාව සමග ඒකාබද්ධ කිරීමයි. බ්රිතාන්ය අධිරාජ්ය සාමාන්ය කාර්ය මණ්ඩලය භූමියේ සිහින් වූ කලාපයේ හමුදා ආරක්ෂාව සඳහා සූදානම් විය.[96] ඊජිප්තුව-සුඩානය සමඟ ආක්රමණශීලී නොවන ගිවිසුමක් ඇති කර ගැනීමට ඉතාලි උත්සාහයන් බ්රිතාන්ය තානාපතිවරයා අවහිර කළේය. නමුත් මහමුද් ජෙරුසලමේ ග්රෑන්ඩ් මුෆ්ටිගේ ආධාරකරුවෙකු විය; යුදෙව්වන් බේරා ගැනීමට අධිරාජ්යයේ උත්සාහයන් සහ සංක්රමණය නැවැත්වීමට මධ්යස්ථ අරාබි ඉල්ලීම් අතර කලාපය හසු විය.[97]

සුඩාන රජය නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු ව්යාපාරයට සෘජුවම යුධමය වශයෙන් සම්බන්ධ විය. 1925 දී පිහිටුවන ලද සුඩාන ආරක්ෂක බලකාය දෙවන ලෝක යුද්ධයේ මුල් ආක්රමණ වලට ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීම සඳහා ක්රියාකාරී කොටසක් ඉටු කළේය. 1940 දී ඉතාලි හමුදා ඉතාලි සෝමාලිලන්තයේ සිට කසාලා සහ අනෙකුත් දේශසීමා ප්රදේශ අත්පත් කර ගත්හ. 1942 දී, බ්රිතාන්ය සහ පොදුරාජ්ය මණ්ඩලීය හමුදා විසින් ඉතාලි යටත් විජිතය ආක්රමණය කිරීමේදී SDF ද දායක විය. අවසන් බ්රිතාන්ය ආණ්ඩුකාරවරයා වූයේ රොබට් ජෝර්ජ් හෝව් ය.

1952 ඊජිප්තු විප්ලවය අවසානයේ සුඩානයේ නිදහස කරා යන ගමනේ ආරම්භය සනිටුහන් කළේය. 1953 දී රාජාණ්ඩුව අහෝසි කිරීමෙන් පසු, ඊජිප්තුවේ නව නායකයන් වන මොහොමඩ් නගුයිබ්, ඔහුගේ මව සුඩාන ජාතිකයෙකු වූ අතර පසුව ගමාල් අබ්දෙල් නසාර් විශ්වාස කළේ සුඩානයේ බ්රිතාන්ය ආධිපත්යය අවසන් කිරීමට ඇති එකම මාර්ගය ඊජිප්තුව ස්වෛරීභාවය පිළිබඳ ප්රකාශ නිල වශයෙන් අත්හැරීම බවයි. ඊට අමතරව ඊජිප්තුව නිදහස ලැබීමෙන් පසු දුප්පත් සුඩානය පාලනය කිරීම දුෂ්කර බව නසාර් දැන සිටියේය. අනෙක් අතට බ්රිතාන්යයන් සුඩාන නිදහස සඳහා ඊජිප්තු පීඩනයට එරෙහි වනු ඇතැයි විශ්වාස කරන ලද මහඩිස්ට් අනුප්රාප්තිකයා වන අබ්දුල්-රහ්මාන් අල්-මහඩි සඳහා ඔවුන්ගේ දේශපාලන සහ මූල්ය ආධාර දිගටම කරගෙන ගියේය. අබ්දුල්-රහ්මාන් මෙයට සමත් වූ නමුත් ඔහුගේ පාලන තන්ත්රය දේශපාලන අකාර්යක්ෂමතාවයෙන් පීඩා විඳි අතර එය උතුරු සහ මධ්යම සුඩානයේ විශාල සහයෝගයක් අහිමි විය. ඊජිප්තුව සහ බ්රිතාන්යය යන දෙඅංශයෙන්ම විශාල අස්ථාවරත්වයක් ඇති වන බවක් දැනුණු අතර, ඒ අනුව උතුරේ සහ දකුණේ සුඩාන කලාප දෙකටම නිදහස අවශ්යද නැතිනම් බ්රිතාන්ය ඉවත්වීමක් අවශ්යද යන්න පිළිබඳව නිදහසේ ඡන්දය දීමට ඉඩ දීමට තීරණය කළහ.

නිදහස (ක්රි.ව. 1956–වර්තමානය)

[සංස්කරණය]

ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී පාර්ලිමේන්තුවක් පිහිටුවීමේ ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස ඡන්ද විමසීම් ක්රියාවලියක් සිදු කරන ලද අතර ඉස්මයිල් අල්-අෂාරි පළමු අගමැති ලෙස තේරී පත් වූ අතර පළමු නූතන සුඩාන රජයට නායකත්වය දුන්නේය.[98] 1956 ජනවාරි 1 වන දින, මහජන මාලිගයේ පැවති විශේෂ උත්සවයකදී, ඊජිප්තු සහ බ්රිතාන්ය ධජ පහත හෙලන ලද අතර, ඒවා වෙනුවට කොළ, නිල් සහ කහ ඉරි වලින් සමන්විත නව සුඩාන ධජය අගමැති ඉස්මයිල් අල්-අසාරි විසින් ඔසවන ලදී. .

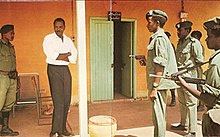

අතෘප්තිය 1969 මැයි 25 වන දින කුමන්ත්රණයකින් අවසන් විය. කුමන්ත්රණ නායක කර්නල් ගෆාර් නිමේරි අගමැති වූ අතර නව පාලනය පාර්ලිමේන්තුව අහෝසි කර සියලු දේශපාලන පක්ෂ නීති විරෝධී කළේය. පාලක මිලිටරි සභාගය තුළ මාක්ස්වාදී සහ මාක්ස්වාදී නොවන කොටස් අතර ආරවුල් 1971 ජූලි මාසයේදී සුඩාන කොමියුනිස්ට් පක්ෂය විසින් මෙහෙයවන ලද කෙටිකාලීන සාර්ථක කුමන්ත්රණයක් ඇති කළේය. දින කිහිපයකට පසු කොමියුනිස්ට් විරෝධී මිලිටරි කොටස් නිමේරි නැවත බලයට පත් කළහ.

1972 දී, ඇඩිස් අබාබා ගිවිසුම උතුරු-දකුණු සිවිල් යුද්ධය නතර කිරීමට සහ ස්වයං පාලනයේ තරමකට හේතු විය. මෙය සිවිල් යුද්ධයේ වසර දහයක විරාමයකට තුඩු දුන් නමුත් ජොන්ග්ලෙයි ඇල ව්යාපෘතියේ ඇමරිකානු ආයෝජනය අවසන් විය. ඉහළ නයිල් ප්රදේශයට වාරි ජලය සැපයීමට සහ ප්රාදේශීය ගෝත්රිකයන් අතර, විශේෂයෙන් ඩින්කා අතර පාරිසරික ව්යසනයක් සහ පුළුල් පරිමාණ සාගතයක් වැලැක්වීම සඳහා මෙය අත්යවශ්ය යැයි සැලකේ. පසුව ඇති වූ සිවිල් යුද්ධයේදී ඔවුන්ගේ මව්බිම වටලා, කොල්ලකෑම්, කොල්ලකෑම් සහ පුළුස්සා දමන ලදී. වසර 20කට වැඩි කාලයක් පුරා පැවති ලේ වැකි සිවිල් යුද්ධයකදී බොහෝ ගෝත්රිකයන් ඝාතනය විය.

1970 ගණන්වල මුල් භාගය වන තෙක්, සුඩානයේ කෘෂිකාර්මික නිමැවුම බොහෝ දුරට අභ්යන්තර පරිභෝජනය සඳහා කැප විය. 1972 දී සුඩාන රජය බටහිර ගැති බවට පත් වූ අතර ආහාර සහ මුදල් බෝග අපනයනය කිරීමට සැලසුම් සකස් කළේය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, 1970 ගනන් පුරා භාණ්ඩ මිල පහත වැටීම සුඩානයට ආර්ථික ගැටළු ඇති කළේය. ඒ අතරම, කෘෂිකර්මාන්තය යාන්ත්රික කිරීමට වැය කළ මුදලින් ණය සේවා පිරිවැය ඉහළ ගියේය. 1978 දී, IMF රජය සමඟ ව්යුහාත්මක ගැලපුම් වැඩසටහනක් සාකච්ඡා කළේය. මෙමගින් යාන්ත්රික අපනයන කෘෂිකාර්මික අංශය තවදුරටත් ප්රවර්ධනය විය. මෙය සුඩානයේ එඬේරුන්ට මහත් දුෂ්කරතා ඇති කළේය. 1976 දී අන්සාර්වරු ලේ වැකි නමුත් අසාර්ථක කුමන්ත්රණයක් දියත් කළහ. නමුත් 1977 ජූලි මාසයේදී ජනාධිපති නිමේරි, අන්සාර් නායක සාදික් අල්-මහඩි හමුවී, හැකි ප්රතිසන්ධානයකට මග විවර කළේය. දේශපාලන සිරකරුවන් සිය ගණනක් නිදහස් කරන ලද අතර අගෝස්තු මාසයේදී සියලුම විරුද්ධවාදීන් සඳහා පොදු සමාවක් ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලදී.

බෂීර් යුගය (1989-2019)

[සංස්කරණය]

1989 ජූනි 30 දින කර්නල් ඕමාර් අල්-බෂීර් ලේ රහිත හමුදා කුමන්ත්රණයක් මෙහෙයවීය.[99] නව හමුදා ආන්ඩුව දේශපාලන පක්ෂ අත්හිටුවා ජාතික මට්ටමින් ඉස්ලාමීය නීති සංග්රහයක් හඳුන්වා දුන්නේය.[100] පසුව, අල්-බෂීර් විසින් හමුදාවේ ඉහළ නිලයන් පිරිසිදු කිරීම් සහ මරණ දණ්ඩනය සිදු කරන ලදී, සංගම්, දේශපාලන පක්ෂ සහ ස්වාධීන පුවත්පත් තහනම් කිරීම සහ ප්රමුඛ දේශපාලන පුද්ගලයින් සහ මාධ්යවේදීන් සිරගත කිරීම.[101] 1993 ඔක්තෝබර් 16 වන දින, අල්-බෂීර් තමා "ජනාධිපති" ලෙස පත් කර ගත් අතර විප්ලවවාදී අණදෙන කවුන්සිලය විසුරුවා හැරියේය. කවුන්සිලයේ විධායක සහ ව්යවස්ථාදායක බලතල අල්-බෂීර් විසින් ගන්නා ලදී.[102] 1996 මහ මැතිවරණයේ දී, නීතිය අනුව මැතිවරණයට ඉදිරිපත් වූ එකම අපේක්ෂකයා ඔහු විය.[103] ජාතික කොන්ග්රස් පක්ෂය (NCP) යටතේ සුඩානය තනි-පක්ෂ රාජ්යයක් බවට පත් විය.[104] 1990 ගණන් වලදී, එවකට ජාතික සභාවේ කථානායකවරයා වූ හසන් අල්-තුරාබි ඉස්ලාමීය මූලධර්මවාදී කණ්ඩායම් වෙත ළඟා වූ අතර ඔසාමා බින් ලාඩන්ට රටට ආරාධනා කළේය.[105] එක්සත් ජනපදය පසුව සුඩානය ත්රස්තවාදයේ රාජ්ය අනුග්රාහකයෙකු ලෙස ලැයිස්තුගත කළේය.[106] අල්කයිඩා විසින් කෙන්යාවේ සහ ටැන්සානියාවේ එක්සත් ජනපද තානාපති කාර්යාලවලට බෝම්බ හෙලීමෙන් පසුව, එක්සත් ජනපදය ඔපරේෂන් ඉන්ෆිනයිට් රීච් දියත් කළ අතර ත්රස්තවාදී කණ්ඩායම සඳහා රසායනික අවි නිෂ්පාදනය කරන බවට එක්සත් ජනපද රජය ව්යාජ ලෙස විශ්වාස කළ අල්-ෂිෆා ඖෂධ කම්හල ඉලක්ක කළේය. අල්-තුරාබිගේ බලපෑම හීන වන්නට පටන් ගත් අතර, වඩාත් ප්රායෝගික නායකත්වයට පක්ෂ වූ අනෙක් අය සුඩානයේ ජාත්යන්තර හුදකලාව වෙනස් කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළහ.[107] ඊජිප්තු ඉස්ලාමීය ජිහාඩයේ සාමාජිකයින් නෙරපා හැරීමෙන් සහ බින් ලාඩන් ඉවත්ව යන ලෙස දිරිමත් කිරීම මගින් එහි විවේචකයින් සනසාලීමට රට කටයුතු කළේය.[108]

2000 ජනාධිපතිවරණයට පෙර, අල්-තුරාබි විසින් ජනාධිපතිවරයාගේ බලතල අඩු කිරීමේ පනතක් ඉදිරිපත් කළ අතර, විසුරුවා හැරීමට නියෝග කිරීමට සහ හදිසි තත්වයක් ප්රකාශ කිරීමට අල්-බෂීර් පොළඹවන ලදී. සුඩාන මහජන විමුක්ති හමුදාව සමඟ ගිවිසුම් අත්සන් කිරීමේ ජනාධිපතිගේ නැවත මැතිවරණ ව්යාපාරය වර්ජනය කරන ලෙස අල්-තුරාබි ඉල්ලා සිටි විට, අල්-බෂීර් සැක කළේ ඔවුන් රජය පෙරලා දැමීමට කුමන්ත්රණය කරන බවයි.[109] හසන් අල්-තුරාබි එම වසරේම පසුව සිරගත කරන ලදී.[110]

2003 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේ දී, සුඩාන රජය විසින් අරාබි නොවන අරාබි ජාතිකයන් හට සුඩාන අරාබිවරුන් වෙනුවෙන් පීඩා කරන බවට චෝදනා කරමින්, සුඩාන විමුක්ති ව්යාපාරය/හමුදා (SLM/A) සහ යුක්තිය සහ සමානතා ව්යාපාරය (JEM) කණ්ඩායම් ආයුධ අතට ගත්හ. ඩාර්ෆුර්. එතැන් පටන් ගැටුම ජන සංහාරයක් ලෙස විස්තර කර ඇත,[111] සහ හේග් හි ජාත්යන්තර අපරාධ අධිකරණය (ICC) අල්-බෂීර්ට අත්අඩංගුවට ගැනීමේ වරෙන්තු දෙකක් නිකුත් කර ඇත.[112][113] ජන්ජාවීඩ් නමින් හැඳින්වෙන අරාබි භාෂාව කතා කරන සංචාරක සටන්කාමීන් බොහෝ කුරිරුකම් සම්බන්ධයෙන් චෝදනා කරති.

2005 ජනවාරි 9 වන දින, දෙවන සුඩාන සිවිල් යුද්ධය අවසන් කිරීමේ අරමුණ ඇතිව රජය සුඩාන මහජන විමුක්ති ව්යාපාරය (SPLM) සමඟ නයිරෝබි විස්තීරණ සාම ගිවිසුම අත්සන් කළේය. සුඩානයේ එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ දූත මණ්ඩලය (UNMIS) එය ක්රියාත්මක කිරීමට සහාය වීම සඳහා එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ ආරක්ෂක කවුන්සිලයේ යෝජනාව 1590 යටතේ පිහිටුවන ලදී. සාම ගිවිසුම 2011 ජනමත විචාරණයට පූර්ව අවශ්යතාවයක් විය: ප්රතිඵලය වූයේ දකුණු සුඩානය වෙන්වීමට පක්ෂව ඒකමතික ඡන්දයකි; අබියි කලාපය අනාගත දිනයකදී තමන්ගේම ජනමත විචාරණයක් පවත්වනු ඇත.

සුඩාන මහජන විමුක්ති හමුදාව (SPLA) නැගෙනහිර සුඩානයේ ක්රියාත්මක කැරලි කණ්ඩායම්වල සන්ධානයක් වන නැගෙනහිර පෙරමුණේ මූලික සාමාජිකයා විය. සාම ගිවිසුමෙන් පසුව, විශාල ෆුලානි සහ බෙජා කොංග්රසය කුඩා රෂයිඩා ෆ්රී සිංහයන් සමඟ ඒකාබද්ධ වීමෙන් පසු 2004 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේදී ඔවුන්ගේ ස්ථානය ලබා ගන්නා ලදී.[114] සුඩාන රජය සහ නැගෙනහිර පෙරමුණ අතර සාම ගිවිසුමක් 2006 ඔක්තෝබර් 14 වන දින අස්මාරාහිදී අත්සන් කරන ලදී. 2006 මැයි 5 වන දින ඩාර්ෆූර් සාම ගිවිසුම අත්සන් කරන ලද අතර, මේ මොහොත දක්වා වසර තුනක් තිස්සේ පැවති ගැටුම අවසන් කිරීම අරමුණු කර ගෙන ඇත.[115] චැඩ්-සුඩාන් ගැටුම (2005-2007) ඇඩ්රේ සටන චැඩ් විසින් යුද්ධ ප්රකාශයක් ආරම්භ කිරීමෙන් පසුව පුපුරා ගියේය.[116] සුඩානයේ සහ චැඩ් රාජ්යයේ නායකයින් 2007 මැයි 3 දින සෞදි අරාබියේදී ගිවිසුමක් අත්සන් කළේ ඔවුන්ගේ රටවල කිලෝමීටර් 1,000 (සැතපුම් 600) දේශසීමා දිගේ ගලා යන ඩාර්ෆුර් ගැටුමෙන් සටන් වැලැක්වීම සඳහා ය.[117]

2007 ජූලි මාසයේදී රට විනාශකාරී ගංවතුරකින් පීඩාවට පත් විය,[118] 400,000 කට අධික ජනතාවක් සෘජුවම පීඩාවට පත් විය.[119] 2009 සිට, සුඩානයේ සහ දකුණු සුඩානයේ ප්රතිවාදී සංචාරක ගෝත්රිකයන් අතර පවතින ගැටුම් මාලාවක් සිවිල් වැසියන් විශාල සංඛ්යාවක් තුවාල ලබා තිබේ.

බෙදීම සහ පුනරුත්ථාපනය කිරීම

[සංස්කරණය]සුඩාන හමුදාව සහ සුඩාන විප්ලවවාදී පෙරමුණ අතර 2010 දශකයේ මුල් භාගයේ දකුණු කොර්ඩෝෆාන් සහ නිල් නයිල් හි සුඩාන ගැටුම ආරම්භ වූයේ 2011 දී දකුණු සුඩාන නිදහස ලැබීමට පෙර මාසවලදී තෙල් පොහොසත් කලාපයක් වන අබියි පිළිබඳ ආරවුලක් ලෙස ය. නාමිකව විසඳන ලද ඩාර්ෆූර්හි සිවිල් යුද්ධයට ද සම්බන්ධ වේ. වසරකට පසුව 2012 හි හෙග්ලිග් අර්බුදය අතරතුර සුඩානය දකුණු සුඩානයට එරෙහිව ජයග්රහණයක් අත්කර ගනු ඇත, දකුණු සුඩානයේ යුනිටි සහ සුඩානයේ දකුණු කොර්ඩෝෆාන් ප්රාන්ත අතර තෙල් පොහොසත් කලාප සම්බන්ධයෙන් යුද්ධයක්. මෙම සිදුවීම් පසුව සුඩාන ඉන්ටිෆාඩා ලෙස හඳුන්වනු ලබන අතර, එය අවසන් වන්නේ 2015 දී නැවත මැතිවරණයක් ඉල්ලා නොසිටින බවට අල්-බෂීර් පොරොන්දු වීමෙන් පසුව 2013 දී පමණි. පසුව ඔහු තම පොරොන්දුව කඩ කර 2015 දී නැවත තේරී පත්වීමට උත්සාහ කළ අතර, එය වර්ජනයකින් ජයග්රහණය කළේය. මැතිවරණය නිදහස් හා සාධාරණ නොවන බව විශ්වාස කළ විපක්ෂය. ඡන්දය ප්රකාශ කිරීමේ ප්රතිශතය අඩු 46%කි.[120]

2017 ජනවාරි 13 වන දින, එක්සත් ජනපද ජනාධිපති බරක් ඔබාමා විසින් විධායක නියෝගයකට අත්සන් කරන ලද අතර එමඟින් සුඩානයට එරෙහිව පනවා ඇති සම්බාධක සහ විදේශයන්හි පැවති එහි රජයේ වත්කම් ඉවත් කරන ලදී. 2017 ඔක්තෝම්බර් 6 දින, පහත දැක්වෙන එක්සත් ජනපද ජනාධිපති ඩොනල්ඩ් ට්රම්ප් විසින් රටට සහ එහි ඛනිජ තෙල්, අපනයන-ආනයන සහ දේපල කර්මාන්ත වලට එරෙහිව ඉතිරිව තිබූ සම්බාධක බොහොමයක් ඉවත් කරන ලදී.[121]

2019 සුඩාන විප්ලවය සහ සංක්රාන්ති රජය

[සංස්කරණය]

2018 දෙසැම්බර් 19 දින, රට විදේශ මුදල් හිඟයකින් සහ සියයට 70 ක උද්ධමනයකින් පීඩා විඳිමින් සිටි අවස්ථාවක, භාණ්ඩ මිල තුන් ගුණයකින් වැඩි කිරීමට රජය ගත් තීරණයෙන් පසුව දැවැන්ත විරෝධතා ආරම්භ විය.[122] මීට අමතරව, වසර 30 කට වැඩි කාලයක් බලයේ සිටි ජනාධිපති අල්-බෂීර් බලයෙන් ඉවත් වීම ප්රතික්ෂේප කළ අතර, එහි ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස විපක්ෂ කණ්ඩායම් එකතු වී ඒකාබද්ධ සන්ධානයක් ඇති විය. ප්රාදේශීය සහ සිවිල් වාර්තාවලට අනුව එම සංඛ්යාව ඊට වඩා බෙහෙවින් වැඩි වුවද, හියුමන් රයිට්ස් වොච්[123] අනුව, ආසන්න වශයෙන් පුද්ගලයන් 40 දෙනෙකුගේ මරණයට තුඩු දුන්, විපක්ෂ නායකයින් සහ විරෝධතාකරුවන් 800කට අධික සංඛ්යාවක් අත්අඩංගුවට ගැනීමෙන් රජය පළිගත්තේය. 2019 අප්රේල් 11 වන දින සුඩාන සන්නද්ධ හමුදා ප්රධාන මූලස්ථානය ඉදිරිපිට දැවැන්ත වාඩිලෑමකින් පසු ඔහුගේ රජය පෙරලා දැමීමෙන් පසු විරෝධතා දිගටම පැවතුනි, ඉන් පසුව කාර්ය මණ්ඩල ප්රධානීන් මැදිහත් වීමට තීරණය කළ අතර ඔවුන් ජනාධිපති අල්-බෂීර් අත්අඩංගුවට ගන්නා ලෙස නියෝග කර ප්රකාශ කළේය. මාස තුනක හදිසි තත්වයක්.[124][125][126] ජූනි 3 වෙනිදා ආරක්ෂක හමුදා විසින් කඳුළු ගෑස් සහ ජීව උණ්ඩ භාවිතා කරමින් වාඩිලෑම විසුරුවා හැරීමෙන් පසු 100 කට අධික පිරිසක් මිය ගියහ.[127][128][129] සුඩානයේ තරුණයින් විරෝධතා මෙහෙයවන බව වාර්තා විය.[130] නිදහස සහ වෙනස සඳහා බලවේග (විරෝධතා සංවිධානය කරන කණ්ඩායම්වල සන්ධානයක්) සහ සංක්රාන්ති හමුදා කවුන්සිලය (පාලක හමුදා රජය) 2019 ජූලි දේශපාලන ගිවිසුමට සහ 2019 අගෝස්තු ව්යවස්ථා කෙටුම්පතට අත්සන් කළ විට විරෝධතා අවසන් විය. සංක්රාන්ති ආයතන සහ ක්රියා පටිපාටිවලට රාජ්ය නායකයා ලෙස සුඩානයේ ඒකාබද්ධ හමුදා-සිවිල් ස්වෛරී කවුන්සිලයක් නිර්මාණය කිරීම, බලයේ අධිකරණ ශාඛාවේ ප්රධානියා ලෙස සුඩානයේ නව අගවිනිසුරුවරයකු, නෙමට් අබ්දුල්ලා කයිර් සහ නව අගමැතිවරයකු ඇතුළත් විය. 2019 අගෝස්තු 21 දින දිවුරුම් දුන් හිටපු අග්රාමාත්ය අබ්දල්ලා හම්ඩොක්, අප්රිකාව සඳහා වූ එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ ආර්ථික කොමිසමේ මීට පෙර සේවය කළ 61 හැවිරිදි ආර්ථික විද්යාඥයෙකි.[131] ආහාර, ඉන්ධන සහ දෘඩ මුදල් හිඟය හේතුවෙන් දැඩි අර්බුදයකට ලක්ව ඇති ආර්ථිකය ස්ථාවර කිරීම අරමුණු කර ගනිමින් ඔහු IMF සහ ලෝක බැංකුව සමඟ සාකච්ඡා ආරම්භ කළේය. හම්ඩොක් වසර දෙකක් පුරා ඇ.ඩො. බිලියන 10 ඇස්තමේන්තු කර ඇති අතර, භීතිය නැවැත්වීමට ප්රමාණවත් වනු ඇති අතර, 2018 අයවැයෙන් 70% කට වඩා සිවිල් යුද්ධයට සම්බන්ධ පියවරයන් සඳහා වියදම් කර ඇති බව පැවසීය. සවුදි අරාබියේ සහ එක්සත් අරාබි එමීර් රාජ්යයේ ආන්ඩු බෂීර් නෙරපා හැරීමෙන් පසු හමුදා කවුන්සිලයට ආධාර කිරීම සඳහා සැලකිය යුතු මුදලක් ආයෝජනය කර ඇත.[132] සැප්තැම්බර් 3 වන දින, හැම්ඩොක් විසින් සිවිල් ඇමතිවරුන් 14 දෙනෙකු පත් කරන ලද අතර, පළමු කාන්තා විදේශ ඇමතිවරිය සහ පළමු කොප්ටික් ක්රිස්ටියන්වරිය ද, කාන්තාවක් ද විය.[133][134] 2021 අගෝස්තු වන විට, රට සංක්රාන්ති ස්වෛරී කවුන්සිලයේ සභාපති අබ්දෙල් ෆටා අල්-බුර්හාන් සහ අගමැති අබ්දල්ලා හම්ඩොක් විසින් ඒකාබද්ධව මෙහෙයවන ලදී.[135]

2021 කුමන්ත්රණය සහ අල්-බුර්හාන් පාලනය

[සංස්කරණය]සුඩාන රජය 2021 සැප්තැම්බර් 21 දින නිවේදනය කළේ හමුදා නිලධාරීන් 40 දෙනෙකු අත්අඩංගුවට ගැනීමට තුඩු දුන් හමුදා කුමන්ත්රණයක් අසාර්ථක උත්සාහයක් ඇති බවයි.[136][137]

කුමන්ත්රණය කිරීමට උත්සාහ කිරීමෙන් මාසයකට පසු, 2021 ඔක්තෝබර් 25 වන දින තවත් හමුදා කුමන්ත්රණයකින් හිටපු අගමැති අබ්දල්ලා හම්ඩොක් ඇතුළු සිවිල් රජය බලයෙන් පහ විය. කුමන්ත්රණය මෙහෙයවන ලද්දේ ජෙනරාල් අබ්දෙල් ෆාටා අල්-බුර්හාන් විසින් පසුව හදිසි තත්වයක් ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලදී.[138][139][140][141] බර්හාන් සුඩානයේ තථ්ය රාජ්ය නායකයා ලෙස බලයට පත් වූ අතර 2021 නොවැම්බර් 11 වන දින නව හමුදාවේ පිටුබලය සහිත රජයක් පිහිටුවීය.[142]

2021 නොවැම්බර් 21 වන දින, සිවිල් පාලනයට සංක්රාන්තිය ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය කිරීම සඳහා බර්හාන් විසින් දේශපාලන ගිවිසුමක් අත්සන් කිරීමෙන් පසු හැම්ඩොක් නැවත අගමැති ලෙස පත් කරන ලදී (බර්හාන් පාලනය තබා ගත්තද). කුමන්ත්රණය අතරතුර අත්අඩංගුවේ පසුවන සියලුම දේශපාලන සිරකරුවන් නිදහස් කිරීම සඳහා වූ කරුණු 14කින් යුත් ගිවිසුම මගින් 2019 ව්යවස්ථාපිත ප්රකාශයක් දේශපාලන සංක්රාන්තියක් සඳහා පදනම ලෙස දිගටම පවතින බව නියම කළේය.[143] හැම්ඩොක් පොලිස් ප්රධානී කලීඩ් මහඩි ඊබ්රාහිම් අල්-ඉමාම් සහ ඔහුගේ දෙවන අණදෙන නිලධාරි අලි ඊබ්රාහිම්ව නෙරපා හැරියේය.[144]

2 ජනවාරි 2022 දින, හැම්ඩොක් මේ දක්වා වූ වඩාත් මාරාන්තික විරෝධතාවයකින් පසුව අගමැති ධුරයෙන් ඉල්ලා අස්වන බව නිවේදනය කළේය.[145] ඔහුගෙන් පසුව ඔස්මන් හුසේන් පත් විය.[146][147] 2022 මාර්තු වන විට කුමන්ත්රණයට විරුද්ධ වීම නිසා ළමුන් 148ක් ඇතුළු 1000කට අධික පිරිසක් රඳවාගෙන සිටි අතර, ස්ත්රී දූෂණ 25ක්[148] සහ ළමුන් 11ක්[148] ඇතුළුව පුද්ගලයන් 87ක් ඝාතනය කර ඇත.[149]

2023–වර්තමානය: අභ්යන්තර ගැටුම්

[සංස්කරණය]

2023 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී - සිවිල් පාලනයට සංක්රමණයක් සඳහා වූ ජාත්යන්තරව තැරැව්කාර සැලැස්මක් ලෙස සාකච්ඡා කරන ලදී - හමුදාපති (සහ තථ්ය ජාතික නායක) අබ්දෙල් ෆටා අල්-බුර්හාන් සහ ඔහුගේ නියෝජ්ය, දැඩි ලෙස සන්නද්ධ පැරාමිලිටරි රැපිඩ් ප්රධානී හෙමෙටි අතර බල අරගල වර්ධනය විය. එය ජන්ජවීඩ් මිලීෂියාවෙන් පිහිටුවන ලද ආධාරක බලකායකි (RSF).[150][151]

2023 අප්රේල් 15 වන දින, ඔවුන්ගේ ගැටුම සිවිල් යුද්ධයක් දක්වා පුපුරා ගියේ හමුදාව සහ ආර්එස්එෆ් අතර - හමුදා, ටැංකි සහ ගුවන් යානා සමඟ කාර්ටූම් වීදිවල ඇති වූ සටන් සමඟිනි. තුන්වන දිනය වන විට, එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවිධානයට අනුව, පුද්ගලයන් 400 ක් මිය ගිය අතර අවම වශයෙන් 3,500 ක් තුවාල ලැබූ බව වාර්තා විය.[152] මියගිය අය අතර ලෝක ආහාර වැඩසටහනේ කම්කරුවන් තිදෙනෙකු ද වූ අතර, රටේ බොහෝ ප්රදේශවල පවතින සාගින්න නොතකා, සුඩානයේ සංවිධානයේ වැඩ කටයුතු අත්හිටුවීමට හේතු විය.[153] සුඩාන ජෙනරාල් යසර් අල්-අට්ටා පැවසුවේ යුඒඊය යුද්ධයේදී භාවිතා කරන ලද ආර්එස්එෆ් වෙත සැපයුම් සපයන බවයි.[154]

සුඩාන සන්නද්ධ හමුදා සහ කඩිනම් සහය හමුදා යන දෙකටම යුද අපරාධ සිදු කළ බවට චෝදනා එල්ල වේ.[155][156] 2023 දෙසැම්බර් 29 වන විට මිලියන 5.8කට අධික පිරිසක් අභ්යන්තරව අවතැන් වූ අතර තවත් මිලියන 1.5කට වැඩි පිරිසක් සරණාගතයන් ලෙස රටින් පලා ගොස් ඇත,[157] සහ මසාලිට් සමූලඝාතනවල කොටසක් ලෙස ඩාර්ෆූර් හි බොහෝ සිවිල් වැසියන් මිය ගොස් ඇති බව වාර්තා වේ.[158] ජෙනීනා නගරයේ 15,000ක් දක්වා මිනිසුන් ඝාතනය විය.[159]

යුද්ධයේ ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස ලෝක ආහාර වැඩසටහන 2024 පෙබරවාරි 22 දින වාර්තාවක් නිකුත් කරමින් කියා සිටියේ සුඩානයේ ජනගහනයෙන් 95%කට වඩා දිනකට ආහාර වේලක් ලබා ගැනීමට නොහැකි බවයි.[160] 2024 අප්රේල් වන විට, එක්සත් ජාතීන්ගේ සංවිධානය වාර්තා කළේ, මිලියන 8.6කට අධික ජනතාවකට තම නිවෙස්වලින් පිටමං කර ඇති අතර, මිලියන 18ක් දැඩි කුසගින්නෙන් පෙළෙන අතර, ඔවුන්ගෙන් මිලියන පහක් හදිසි මට්ටමේ සිටින බවයි.[161] 2024 මැයි මාසයේදී එක්සත් ජනපද රජයේ නිලධාරීන් ඇස්තමේන්තු කළේ පසුගිය වසර තුළ පමණක් අවම වශයෙන් මිනිසුන් 150,000 ක් යුද්ධයෙන් මිය ගොස් ඇති බවයි.[162] විශේෂයෙන්ම එල් ෆාෂර් නගරය අවට කළු ජාතික ආදිවාසී ප්රජාවන් වෙත ආර්එස්එෆ් පැහැදිලිවම ඉලක්ක කිරීම, ඩාර්ෆූර් කලාපයේ තවත් ජන සංහාරයක් සමඟ ඉතිහාසය පුනරාවර්තනය වීමේ අවදානම පිළිබඳව ජාත්යන්තර නිලධාරීන් අනතුරු අඟවා ඇත.[162]

2024 මැයි 31 දින, සුඩානයේ මානුෂීය අර්බුදය විසඳීම සඳහා එක්සත් ජනපද කොන්ග්රස් සභික එලිනෝර් හෝම්ස් නෝටන් විසින් නියෝජිත මන්ත්රී මණ්ඩලයේදී සම්මන්ත්රණයක් කැඳවන ලදී. එක්සත් අරාබි එමීර් රාජ්යයේ සුඩානයට සම්බන්ධ යුද අපරාධ සහ ආයුධ අපනයනය ඇතුළු රාජ්ය දෙපාර්තමේන්තුවේ වාර්තාවක් සමුළුවේ සාකච්ඡාවේ මූලික අවධානය යොමු විය. සූඩානයේ සහ යේමනයේ සිවිල් යුද්ධයේදී ආර්එස්එෆ් භාවිතා කිරීමේදී එක්සත් අරාබි එමීර් රාජ්යයේ භූමිකාව “නැවැත්විය යුතු” බව ප්රකාශ කරමින් පැනලිස්ට් කථිකයෙකු වන සභා මන්ත්රී මොහොමඩ් සෙයිෆෙල්ඩීන්, සුඩානයට එක්සත් අරාබි එමීර් රාජ්යයේ මැදිහත්වීම නතර කරන ලෙස ඉල්ලා සිටියේය. සීෆෙල්ඩීන්, තවත් මණ්ඩලයේ සාමාජිකයෙකු වන හගීර් එස් එල්ෂේක් සමගින්, සුඩානය තුල සටන්කාමී කන්ඩායමේ විනාශකාරී භූමිකාව පෙන්වා දෙමින්, RSF සඳහා වන සියලු සහයෝගය නතර කරන ලෙස ජාත්යන්තර ප්රජාවෙන් ඉල්ලා සිටියේය. සුඩාන යුද්ධය පිළිබඳව දැනුවත් කිරීම සඳහා සමාජ මාධ්ය භාවිතා කිරීමට සහ එක්සත් අරාබි එමීර් රාජ්යයට ආයුධ අලෙවි කිරීම නැවැත්වීමට එක්සත් ජනපදයෙන් තේරී පත් වූ නිලධාරීන්ට බලපෑම් කිරීමට එල්ෂේක් නිර්දේශ කළේය.[163]

යොමු කිරීම්

[සංස්කරණය]- ^ Osypiński, Piotr; Osypińska, Marta; Gautier, Achilles (2011). "Affad 23, a Late Middle Palaeolithic Site With Refitted Lithics and Animal Remains in the Southern Dongola Reach, Sudan". Journal of African Archaeology. 9 (2): 177–188. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10186. ISSN 1612-1651. JSTOR 43135549. OCLC 7787802958. S2CID 161078189.

- ^ Osypiński, Piotr (2020). "Unearthing Pan-African crossroad? Significance of the middle Nile valley in prehistory" (PDF). National Science Centre. 1 August 2023 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 1 August 2023.

- ^ Osypińska, Marta (2021). "Animals in the history of the Middle Nile" (PDF). From Faras to Soba: 60 years of Sudanese–Polish cooperation in saving the heritage of Sudan. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology/University of Warsaw. p. 460. ISBN 9788395336256. OCLC 1374884636.

- ^ Osypińska, Marta; Osypiński, Piotr (2021). "Exploring the oldest huts and the first cattle keepers in Africa" (PDF). From Faras to Soba: 60 years of Sudanese–Polish cooperation in saving the heritage of Sudan. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology/University of Warsaw. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9788395336256. OCLC 1374884636.

- ^ "Sudan A Country Study". Countrystudies.us.

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y. (1993). "Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships". History in Africa. 20 (7): 129–54. doi:10.2307/3171969. JSTOR 317196. S2CID 162330365.

- ^ Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette (2009). "The Kingdom of Kush: An African Centre on the Periphery of the Bronze Age World System". Norwegian Archaeological Review. 42 (1): 50–70. doi:10.1080/00293650902978590. S2CID 154430884.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Nubia, Richard A. Lobban Jr., p. 254.

- ^ De Mola, Paul J. "Interrelations of Kerma and Pharaonic Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/487/

- ^ "Jebal Barkal: History and Archaeology of Ancient Napata". 2 ජූනි 2013 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 21 මාර්තු 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2016). Writings from Ancient Egypt. United Kingdom: Penguin Classics. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-14-139595-1.

- ^ Flavius Josephus. 'Antiquities of the Jews'. Whiston 2-10-2.

- ^ Edwards, David N. (2005). Nubian Past : an Archaeology of the Sudan. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-48276-6. OCLC 437079538.

- ^ a b Emberling, Geoff; Davis, Suzanne (2019). "A Cultural History of Kush: Politics, Economy, and Ritual Practice". Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond (PDF). Kelsey Museum of Archaeology. pp. 5–6, 10–11. ISBN 978-0-9906623-9-6. සම්ප්රවේශය 3 November 2021.

- ^ Takacs, Sarolta Anna; Cline, Eric H. (17 July 2015). The Ancient World (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45839-5.

- ^ Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-193825-7.

- ^ Connah, Graham (2004). Forgotten Africa: An Introduction to Its Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0-415-30590-X. සම්ප්රවේශය 3 November 2021.

- ^ Unseth, Peter (1 July 1998). "Semantic Shift on a Geographical Term". The Bible Translator. 49 (3): 323–324. doi:10.1177/026009359804900302. S2CID 131916337.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංකය: 26.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංක: 16–22.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංක: 24, 26.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංක: 16–17.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංකය: 77.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංක: 68–70.

- ^ Hasan 1967, පිටු අංකය: 31.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංක: 77–78.

- ^ Shinnie 1978, පිටු අංකය: 572.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංකය: 84.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංකය: 101.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංකය: 89.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, පිටු අංකය: 264.

- ^ Martens-Czarnecka 2015, පිටු අංක: 249–265.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංකය: 254.

- ^ Edwards 2004, පිටු අංකය: 237.

- ^ Adams 1977, පිටු අංකය: 496.

- ^ Adams 1977, පිටු අංකය: 482.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංක: 236–239.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංක: 344–345.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංකය: 88.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංකය: 252.

- ^ Hasan 1967, පිටු අංකය: 176.

- ^ Hasan 1967, පිටු අංකය: 145.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංක: 143–145.

- ^ Ruffini 2012, පිටු අංකය: 256.

- ^ Owens, Travis (June 2008). Beleaguered Muslim Fortresses And Ethiopian Imperial Expansion From The 13th To The 16th Century (PDF) (Masters). Naval Postgraduate School. p. 23. 12 November 2020 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත (PDF). සම්ප්රවේශය 22 June 2020.

- ^ Levtzion & Pouwels 2000, පිටු අංකය: 229.

- ^ Welsby 2002, පිටු අංකය: 255.

- ^ Vantini 1975, පිටු අංක: 786–787.

- ^ Hasan 1967, පිටු අංකය: 133.

- ^ Vantini 1975, පිටු අංකය: 784.

- ^ Vantini 2006, පිටු අංක: 487–489.

- ^ Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංක: 12–30.

- ^ Holt & Daly 2000, පිටු අංකය: 25.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංක: 25–26.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 26.

- ^ Loimeier 2013, පිටු අංකය: 150.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 31.

- ^ Loimeier 2013, පිටු අංක: 151–152.

- ^ Werner 2013, පිටු අංක: 177–184.

- ^ Peacock 2012, පිටු අංකය: 98.

- ^ Peacock 2012, පිටු අංක: 96–97.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 35.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංක: 36–40.

- ^ Adams 1977, පිටු අංකය: 601.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 78.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 88.

- ^ Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 24-25.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංක: 94–95.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 98.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, පිටු අංකය: 382.

- ^ Loimeier 2013, පිටු අංකය: 152.

- ^ Spaulding 1985, පිටු අංක: 210–212.

- ^ Adams 1977, පිටු අංක: 557–558.

- ^ Edwards 2004, පිටු අංකය: 260.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංක: 28–29.

- ^ Hesse 2002, පිටු අංකය: 50.

- ^ Hesse 2002, පිටු අංක: 21–22.

- ^ McGregor 2011, Table 1.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 110.

- ^ McGregor 2011, පිටු අංකය: 132.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 123.

- ^ Holt & Daly 2000, පිටු අංකය: 31.

- ^ O'Fahey & Spaulding 1974, පිටු අංකය: 126.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Tubiana 2007, පිටු අංකය: 9.

- ^ a b O'Fahey & Tubiana 2007, පිටු අංකය: 2.

- ^ Churchill 1902, පිටු අංකය: [page needed].

- ^ Rudolf Carl Freiherr von Slatin; Sir Francis Reginald Wingate (1896). Fire and Sword in the Sudan. E. Arnold. සම්ප්රවේශය 26 June 2013.

- ^ Domke, D. Michelle (November 1997). "ICE Case Studies; Case Number: 3; Case Identifier: Sudan; Case Name: Civil War in the Sudan: Resources or Religion?". Inventory of Conflict and Environment. 9 December 2000 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 January 2011 – via American University School of International Service.

- ^ Humphries, Christian (2001). Oxford World Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 644. ISBN 0195218183.

- ^ Holt. A Modern History of the Sudan. New York: Groves Press Inc.

- ^ Daly, පිටු අංකය: 346.

- ^ Morewood 2005, පිටු අංකය: 4.

- ^ Daly, පිටු අංක: 457–459.

- ^ Morewood 1940, පිටු අංක: 94–95.

- ^ Arthur Henderson, 8 May 1936 quoted in Daly, p. 348

- ^ Sir Miles Lampson, 29 September 1938; Morewood, p. 117

- ^ Morewood, පිටු අංක: 164–165.

- ^ "Brief History of the Sudan". Sudan Embassy in London. 20 November 2008. 20 November 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Factbox – Sudan's President Omar Hassan al-Bashir". Reuters. 14 July 2008. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 January 2011.

- ^ Bekele, Yilma (12 July 2008). "Chickens Are Coming Home To Roost!". Ethiopian Review. Addis Ababa. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 January 2011.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-674-01090-1.

- ^ Walker, Peter (14 July 2008). "Profile: Omar al-Bashir". The Guardian. London. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 January 2011.

- ^ The New York Times. 16 March 1996. p. 4.

- ^ "History of the Sudan". HistoryWorld. n.d.. http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=aa86. ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 13 January 2011.

- ^ Shahzad, Syed Saleem (23 February 2002). "Bin Laden Uses Iraq To Plot New Attacks". Asia Times. Hong Kong. Archived from the original on 20 October 2002. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Families of USS Cole Victims Sue Sudan for $105 Million". Fox News Channel. Associated Press. 13 March 2007. 6 November 2018 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

- ^ Fuller, Graham E. (2004). The Future of Political Islam. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4039-6556-1.

- ^ Wright, Lawrence (2006). The Looming Tower. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 221–223. ISBN 978-0-307-26608-8.

- ^ "Profile: Sudan's President Bashir". BBC News. 25 November 2003. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 January 2011.

- ^ Ali, Wasil (12 May 2008). "Sudanese Islamist Opposition Leader Denies Link with Darfur Rebels". Sudan Tribune. Paris. 12 April 2020 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ "ICC Prosecutor Presents Case Against Sudanese President, Hassan Ahmad al Bashir, for Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes in Darfur" (Press release). Office of the Prosecutor, International Criminal Court. 14 July 2008. 25 March 2009 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "Warrant issued for Sudan's Bashir". BBC News. 4 March 2009. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.

- ^ Lynch, Colum; Hamilton, Rebecca (13 July 2010). "International Criminal Court Charges Sudan's Omar Hassan al-Bashir with Genocide". The Washington Post. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 January 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "UNMIS Media Monitoring Report" (PDF). United Nations Mission in Sudan. 4 January 2006. 21 March 2006 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "Darfur Peace Agreement". US Department of State. 8 May 2006.

- ^ "Restraint Plea to Sudan and Chad". Al Jazeera. Agence France-Presse. 27 December 2005. 10 October 2006 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "Sudan, Chad Agree To Stop Fighting". China Daily. Beijing. Associated Press. 4 May 2007.

- ^ "UN: Situation in Sudan could deteriorate if flooding continues". International Herald Tribune. Paris. Associated Press. 6 August 2007. 26 February 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ "Sudan Floods: At Least 365,000 Directly Affected, Response Ongoing" (Press release). UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Relief Web. 6 August 2007. 20 August 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 13 January 2011.

- ^ "Omar al-Bashir wins Sudan elections by a landslide". BBC News. 27 April 2015. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 April 2019.

- ^ Wadhams, Nick; Gebre, Samuel (6 October 2017). "Trump Moves to Lift Most Sudan Sanctions". Bloomberg Politics. සම්ප්රවේශය 6 October 2017.

- ^ "Sudan December 2018 riots: Is the regime crumbling?". CMI – Chr. Michelsen Institute (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Sudan: Protesters Killed, Injured". Human Rights Watch (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 9 April 2019. සම්ප්රවේශය 30 June 2019.

- ^ "Sudan military coup topples Bashir". 11 April 2019. සම්ප්රවේශය 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Sudan's Omar al-Bashir vows to stay in power as protests rage | News". Al Jazeera. 9 January 2019. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 April 2019.

- ^ Arwa Ibrahim (8 January 2019). "Future unclear as Sudan protesters and president at loggerheads | News". Al Jazeera. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 April 2019.

- ^ "Sudan's security forces attack long-running sit-in". BBC News. 3 June 2019.

- ^ ""Chaos and Fire" – An Analysis of Sudan's June 3, 2019 Khartoum Massacre – Sudan". ReliefWeb (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 5 March 2020.

- ^ "African Union suspends Sudan over violence against protestors – video". The Guardian (බ්රිතාන්ය ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 7 June 2019. ISSN 0261-3077. සම්ප්රවේශය 8 June 2019.

- ^ "'They'll have to kill all of us!'". BBC News (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 30 June 2019.

- ^ "We recognize Hamdok as leader of Sudan's transition: EU, Troika envoys". Sudan Tribune. 27 October 2021. 27 October 2021 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 27 October 2021.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Khalid (24 August 2019). "Sudan needs up to $10 billion in aid to rebuild economy, new PM says". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Sudan's PM selects members of first cabinet since Bashir's ouster". Reuters. 3 September 2019. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Women take prominent place in Sudanese politics as Abdalla Hamdok names cabinet". The National. 4 September 2019.

- ^ "Sudan Threatens to Use Military Option to Regain Control over Border with Ethiopia". Asharq Al-Awsat. 17 August 2021. සම්ප්රවේශය 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Coup attempt fails in Sudan – state media". BBC News (බ්රිතාන්ය ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 21 September 2021. සම්ප්රවේශය 21 September 2021.

- ^ Nima Elbagir and Yasir Abdullah (21 September 2021). "Sudan foils coup attempt and 40 officers arrested, senior officials say". CNN. සම්ප්රවේශය 21 September 2021.

- ^ "Sudan's civilian leaders arrested – reports". www.msn.com.

- ^ "Sudan Officials Detained, Communication Lines Cut in Apparent Military Coup". Bloomberg.com (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 25 October 2021.

- ^ "Sudan's civilian leaders arrested amid coup reports". BBC News (බ්රිතාන්ය ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 25 October 2021.

- ^ Magdy, Samy. "Gov't officials detained, phones down in possible Sudan coup". ABC News (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්).

- ^ "Sudan army chief names new governing Sovereign Council". Al Jazeera. 11 November 2021. 21 March 2023 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Sudan's Hamdok reinstated as PM after political agreement signed". www.aljazeera.com (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 21 November 2021.

- ^ Staff (27 November 2021). "Reinstated Sudanese PM Hamdok dismisses police chiefs". Al Jazeera.com (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Sudan PM Abdalla Hamdok resigns after deadly protest". www.aljazeera.com (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Sudan's Burhan forms caretaker government". sudantribune.com. 20 February 2022. 24 January 2022 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 19 February 2022.

- ^ "Acting Council of Ministers Approves General Budget for Year 2022". MSN. 2022-02-19 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 2022-02-19.

- ^ a b Bachelet, Michelle (7 March 2022). "Oral update on the situation of human rights in the Sudan – Statement by United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights". ReliefWeb/ 49th Session of the UN Human Rights Council (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 22 March 2022.

- ^ Associated Press (18 March 2022). "Sudan group says 187 wounded in latest anti-coup protests". ABC News (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 18 March 2022 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Fighting continues in Sudan despite humanitarian pause". France 24. 2023-04-16. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-04-16.

- ^ El-Bawab, Nadine (16 April 2023). "Clashes erupt in Sudan between army, paramilitary group over government transition". ABC News. සම්ප්රවේශය 16 April 2023.

- ^ Masih, Niha; Pietsch, Bryan; Westfall, Sammy; Berger, Miriam (2023-04-18). "What's behind the fighting in Sudan, and what is at stake?". The Washington Post. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-05-03.

- ^ Jeffery, Jack; Magdy, Samy (17 April 2023). "Sudan's generals battle for 3rd day; death toll soars to 185". Associated Press.

- ^ Eltahir, Nafisa (2023-11-28). "Sudanese general accuses UAE of supplying paramilitary RSF". Reuters (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-12-19.

- ^ "War crimes and civilian suffering in Sudan". Amnesty International (ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). 2023-08-02. 2023-09-25 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 2023-09-30.

- ^ "US declares warring factions in Sudan have committed war crimes". Al Jazeera. 6 December 2023.

- ^ "DTM Sudan – Monthly Displacement Overview (04)". IOM UN Migration. 29 December 2023. 30 December 2023 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Genocide returns to Darfur". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. 10 November 2023 දින පැවති මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත. සම්ප්රවේශය 11 November 2023.

- ^ "Ethnic killings in one Sudan city left up to 15,000 dead: UN report". The Business Standard. 20 January 2024.

- ^ "Over 95 Percent Of Sudanese Cannot Afford A Meal A Day: WFP". Barron's.

- ^ "Sudan violence: The horrifying statistics behind the brutal conflict - and still the death toll is unknown". Sky News. 17 April 2024.

- ^ a b Bariyo, Nicholas; Steinhauser, Gabriele. "Genocide Survivors in Darfur Are Caught in Another Brutal Battle". The Wall Street Journal. සම්ප්රවේශය 2024-06-01.

- ^ "Congressional Briefing: Report on UAE Intervention in Sudan, War Crimes, and Arms Export". Washington Center For Human Rights. 2 June 2024. 3 June 2024 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 4 June 2024.