සුඩානයේ ආර්ථිකය

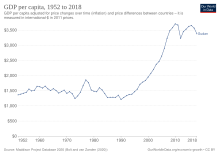

In 2010, Sudan was considered the 17th-fastest-growing economy[1] in the world and the rapid development of the country largely from oil profits even when facing international sanctions was noted by The New York Times in a 2006 article.[2] Because of the secession of South Sudan, which contained about 75 percent of Sudan's oilfields,[3] Sudan entered a phase of stagflation, GDP growth slowed to 3.4 percent in 2014, 3.1 percent in 2015 and was projected to recover slowly to 3.7 percent in 2016 while inflation remained as high as 21.8% 2015 වන විට[update].[4] Sudan's GDP fell from US$123.053 billion in 2017 to US$40.852 billion in 2018.[5]

Even with the oil profits before the secession of South Sudan, Sudan still faced formidable economic problems, and its growth was still a rise from a very low level of per capita output. The economy of Sudan has been steadily growing over the 2000s, and according to a World Bank report the overall growth in GDP in 2010 was 5.2 percent compared to 2009 growth of 4.2 percent.[6] This growth was sustained even during the war in Darfur and period of southern autonomy preceding South Sudan's independence.[7][8] Oil was Sudan's main export, with production increasing dramatically during the late 2000s, in the years before South Sudan gained independence in July 2011. With rising oil revenues, the Sudanese economy was booming, with a growth rate of about nine percent in 2007. The independence of oil-rich South Sudan, however, placed most major oil fields out of the Sudanese government's direct control and oil production in Sudan fell from around 450,000 barrels per day (72,000 m3/d) to under 60,000 barrels per day (9,500 m3/d). Production has since recovered to hover around 250,000 barrels per day (40,000 m3/d) for 2014–15.[9]

To export oil, South Sudan relies on a pipeline to Port Sudan on Sudan's Red Sea coast, as South Sudan is a landlocked country, as well as the oil refining facilities in Sudan. In August 2012, Sudan and South Sudan agreed to a deal to transport South Sudanese oil through Sudanese pipelines to Port Sudan.[10]

The People's Republic of China is one of Sudan's major trading partners, China owns a 40 percent share in the Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company.[11] The country also sells Sudan small arms, which have been used in military operations such as the conflicts in Darfur and South Kordofan.[12]

While historically agriculture remains the main source of income and employment hiring of over 80 percent of Sudanese, and makes up a third of the economic sector, oil production drove most of Sudan's post-2000 growth. Currently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is working hand in hand with Khartoum government to implement sound macroeconomic policies. This follows a turbulent period in the 1980s when debt-ridden Sudan's relations with the IMF and World Bank soured, culminating in its eventual suspension from the IMF.[13]

According to the Corruptions Perception Index, Sudan is one of the most corrupt nations in the world.[14] According to the Global Hunger Index of 2013, Sudan has an GHI indicator value of 27.0 indicating that the nation has an 'Alarming Hunger Situation.' It is rated the fifth hungriest nation in the world.[15] According to the 2015 Human Development Index (HDI) Sudan ranked the 167th place in human development, indicating Sudan still has one of the lowest human development rates in the world.[16] In 2014, 45% of the population lives on less than US$3.20 per day, up from 43% in 2009.[17]

විද්යාව සහ පර්යේෂණ

[සංස්කරණය]Sudan has around 25–30 universities; instruction is primarily in Arabic or English. Education at the secondary and university levels has been seriously hampered by the requirement that most males perform military service before completing their education.[18] In addition, the "Islamisation" encouraged by president Al-Bashir alienated many researchers: the official language of instruction in universities was changed from English to Arabic and Islamic courses became mandatory. Internal science funding withered.[19] According to UNESCO, more than 3,000 Sudanese researchers left the country between 2002 and 2014. By 2013, the country had a mere 19 researchers for every 100,000 citizens, or 1/30 the ratio of Egypt, according to the Sudanese National Centre for Research. In 2015, Sudan published only about 500 scientific papers.[19] In comparison, Poland, a country of similar population size, publishes on the order of 10,000 papers per year.[20]

Sudan's National Space Program has produced multiple CubeSat satellites, and has plans to produce a Sudanese communications satellite (SUDASAT-1) and a Sudanese remote sensing satellite (SRSS-1). The Sudanese government contributed to an offer pool for a private-sector ground surveying Satellite operating above Sudan, Arabsat 6A, which was successfully launched on 11 April 2019, from the Kennedy Space Center.[21] Sudanese president Omar Hassan al-Bashir called for an African Space Agency in 2012, but plans were never made final.[22]

යොමු කිරීම්

[සංස්කරණය]- ^ "Economy". Government of South Sudan. 20 October 2009. 13 July 2011 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (24 October 2006). "Sudanese civil war? Not Where the Oil Wealth Flows". The New York Times. සම්ප්රවේශය 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Sudan Economic Outlook". African Development Bank. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Sudan Economic Outlook". African Development Bank. 29 March 2019.

- ^ "GDP (current US$) – Sudan | Data". data.worldbank.org.

- ^ "Sudan". The World Factbook. U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. ISSN 1553-8133. සම්ප්රවේශය 10 July 2011.

- ^ "South Sudan Gets Ready for Independence". Al Jazeera. 21 June 2011. සම්ප්රවේශය 23 June 2011.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (20 June 2011). "As Secession Nears, Sudan Steps Up Drive to Stop Rebels". The New York Times. සම්ප්රවේශය 23 June 2011.

- ^ "Edit Action", Definitions (Qeios), 7 February 2020,

- ^ Maasho, Aaron (3 August 2012). "Sudan, South Sudan reach oil deal, will hold border talks". Reuters.

- ^ "The 'Big 4' – How oil revenues are connected to Khartoum". Amnesty International USA. 3 October 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 March 2009.

- ^ Herbst, Moira (14 March 2008). "Oil for China, Guns for Darfur". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. New York. 5 April 2008 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 14 March 2009.

- ^ Brown 1992, පිටු අංකය: [page needed].

- ^ Corruption Perceptions Index 2013. Full table and rankings සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 3 දෙසැම්බර් 2013 at archive.today. Transparency International. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide: 2013 Global Hunger Index – The challenge of hunger: Building Resilience to Achieve Food and Nutrition Security. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin. October 2013.

- ^ "The 2013 Human Development Report – "The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World"". HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. pp. 144–147. 26 December 2018 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $3.20 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) – Sudan | Data". data.worldbank.org. සම්ප්රවේශය 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Sudan country profile" (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. December 2004. සම්ප්රවේශය 31 May 2013.

- ^ a b Nordling, Linda (15 December 2017). "Sudan seeks a science revival". Science. 358 (6369): 1369. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1369N. doi:10.1126/science.358.6369.1369. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29242326.

- ^ "The top 20 countries for scientific output". www.openaccessweek.org. 17 March 2014 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 16 December 2017.

- ^ Africa, Space in (23 July 2019). "Inside Sudan's National Space Programme". Space in Africa (ඇමෙරිකානු ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). සම්ප්රවේශය 7 March 2023.

- ^ Smith, David; correspondent, Africa (6 September 2012). "Sudanese president calls for African space agency". The Guardian (බ්රිතාන්ය ඉංග්රීසි බසින්). ISSN 0261-3077. සම්ප්රවේශය 7 March 2023.