උගන්ඩාව

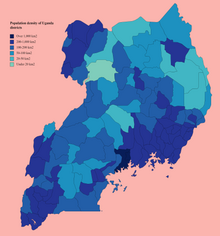

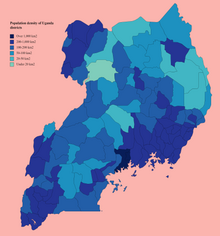

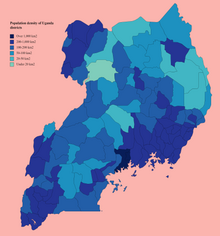

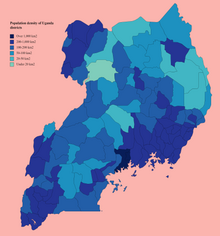

උගන්ඩාව,[lower-alpha 1] නිල වශයෙන් උගන්ඩා ජනරජය,[lower-alpha 2] නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාවේ ගොඩබිම් සහිත රටකි. රට නැගෙනහිරින් කෙන්යාව, උතුරින් දකුණු සුඩානය, බටහිරින් කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය, නිරිත දෙසින් රුවන්ඩාව සහ දකුණින් ටැන්සානියාව මායිම් වේ. රටේ දකුණු කොටසට කෙන්යාව සහ ටැන්සානියාව සමඟ බෙදාගත් වික්ටෝරියා විලෙහි සැලකිය යුතු කොටසක් ඇතුළත් වේ. උගන්ඩාව අප්රිකානු මහා විල් කලාපයේ පිහිටා ඇත, නයිල් ද්රෝණිය තුළ පිහිටා ඇති අතර විවිධ නමුත් සාමාන්යයෙන් වෙනස් කරන ලද සමක දේශගුණයක් ඇත. 2023 වන විට, එහි ජනගහනය මිලියන 49.6 ක් පමණ වන අතර, එයින් මිලියන 8.5 ක් අගනුවර සහ විශාලතම නගරය වන කම්පාලා හි වාසය කරයි.

උගන්ඩාව නම් කර ඇත්තේ කම්පාලා අගනුවර ද ඇතුළුව රටේ දකුණේ විශාල කොටසක් ආවරණය වන බුගන්ඩා රාජධානියෙන් වන අතර ලුගන්ඩා භාෂාව රට පුරා බහුලව භාවිතා වේ. 1894 සිට, ප්රදේශය එක්සත් රාජධානිය විසින් ආරක්ෂිත ප්රදේශයක් ලෙස පාලනය කරන ලද අතර, එය භූමිය පුරා පරිපාලන නීතිය ස්ථාපිත කරන ලදී. උගන්ඩාව 1962 ඔක්තෝබර් 9 දින එක්සත් රාජධානියෙන් නිදහස ලබා ගත්තේය. එතැන් සිට කාල සීමාව ඉඩි අමීන්ගේ නායකත්වයෙන් වසර අටක් පුරා පැවති මිලිටරි ආඥාදායකත්වය ඇතුළු ප්රචණ්ඩ ගැටුම් වලින් සලකුණු විය.

"පාසල් හෝ වෙනත් අධ්යාපන ආයතනවල ඉගැන්වීමේ මාධ්යයක් ලෙස හෝ නීතියෙන් නියම කර ඇති පරිදි ව්යවස්ථාදායක, පරිපාලන හෝ අධිකරණ කටයුතු සඳහා වෙනත් ඕනෑම භාෂාවක් භාවිතා කළ හැකි බව" ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාවේ සඳහන් වුවද රාජ්ය භාෂාව ඉංග්රීසි වේ. මධ්යම ප්රදේශය පදනම් කරගත් භාෂාවක් වන ලුගන්ඩා, රටේ මධ්යම සහ අග්නිදිග ප්රදේශ පුරා බහුලව කතා කරන අතර, ටෙසෝ භාෂාව (දේශීයව අටෙසෝ), ලැන්ගෝ, අචෝලි, රූන්යෝරෝ, රුන්යන්කෝලේ, රුකිගා, ලුඕ ඇතුළු තවත් භාෂා කිහිපයක් ද කතා කරයි. රුටූරෝ, සමියා, ජොපදෝලා සහ ලුසෝගා. 2005 දී විදේශීය සහ මධ්යස්ථ යැයි සැලකෙන ස්වහීලී භාෂාව උගන්ඩාවේ දෙවන නිල භාෂාව ලෙස යෝජනා කරන ලද නමුත් මෙය තවමත් පාර්ලිමේන්තුව විසින් අනුමත කර නොමැත. කෙසේ වෙතත්, 2022 දී උගන්ඩාව පාසල් විෂය මාලාවේ ස්වහීලී අනිවාර්ය විෂයයක් කිරීමට තීරණය කළේය.

උගන්ඩාවේ වත්මන් ජනාධිපති යොවේරි කගුටා මුසවේනි වන අතර ඔහු වසර හයක ගරිල්ලා යුද්ධයකින් පසු 1986 ජනවාරි මාසයේදී බලයට පත්විය. ජනාධිපතිවරයාගේ ධුර කාල සීමාවන් ඉවත් කරන ලද ව්යවස්ථාමය සංශෝධනවලින් පසුව, ඔහුට 2011, 2016 සහ 2021 මහ මැතිවරණවලදී පෙනී සිටීමට හැකි වූ අතර ජනාධිපති ලෙස තේරී පත් විය.

ඉතිහාසය[සංස්කරණය]

පූර්ව යටත් විජිත උගන්ඩාව[සංස්කරණය]

මීට වසර 3,000 කට පෙර බන්ටු කථිකයන් දකුණට පැමිණෙන තෙක් සහ නිලෝටික් කථිකයන් ඊසානදිගට පැමිණෙන තෙක් උගන්ඩාවේ බොහෝමයක් මධ්යම සුඩානික් සහ කුලියාක් භාෂාව කතා කරන ගොවීන් සහ එඬේරුන් විසින් ජනාවාස විය. ක්රිස්තු වර්ෂ 1500 වන විට, ඔවුන් සියල්ලන්ම එල්ගොන් කන්දට දකුණින්, නයිල් ගඟට සහ ක්යෝගා විලට දකුණින් පිහිටි බන්ටු කතා කරන සංස්කෘතීන්ට උකහා ගෙන ඇත.[3]

වාචික සම්ප්රදාය සහ පුරාවිද්යාත්මක අධ්යයනයන්ට අනුව, කිටාරා අධිරාජ්යය උතුරු විල් වන ඇල්බට් සහ ක්යෝගාවේ සිට දකුණු විල් වික්ටෝරියා සහ ටැන්ගානිකා දක්වා මහා විල් ප්රදේශයේ වැදගත් කොටසක් ආවරණය කළේය.[4] කිටාරා ටූරෝ, අන්කෝලේ සහ බුසෝගා රාජධානිවල පූර්වගාමියා ලෙස ප්රකාශ කරනු ලැබේ.[5]

සමහර ලුඕ කිටාරා ආක්රමණය කර එහි බන්ටු සමාජය සමඟ එකතු වී, බුන්යෝරෝ-කිටාරා හි වත්මන් ඔමුකාමා (පාලක) ගේ බයිටෝ රාජවංශය ස්ථාපිත කළේය.[6]

අරාබි වෙළඳුන් 1830 ගණන් වලදී නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාවේ ඉන්දියානු සාගර වෙරළ තීරයේ සිට වෙළඳාම සහ වාණිජ්යය සඳහා ගොඩබිමට සංක්රමණය විය.[7] 1860 ගණන්වල අගභාගයේදී, මැද-බටහිර උගන්ඩාවේ බුන්යොරෝ ඊජිප්තුවේ අනුග්රහය ලබන නියෝජිතයන් විසින් උතුරේ සිට තර්ජනයට ලක් විය.[8] නැඟෙනහිර අප්රිකානු වෙරළ තීරයේ වෙළදාම සොයා ගිය අරාබි වෙළඳුන් මෙන් නොව, මෙම නියෝජිතයන් විදේශ ආක්රමණ ප්රවර්ධනය කරමින් සිටියහ. 1869 දී, ඊජිප්තුවේ කෙදිවේ ඉස්මයිල් පාෂා, වික්ටෝරියා විලෙහි මායිම්වලට උතුරින් සහ ඇල්බට් විලට නැගෙනහිරින් සහ "ගොන්ඩොකෝරෝ හි දකුණු" ප්රදේශ ඈඳා ගැනීමට උත්සාහ කරමින්,[9] බ්රිතාන්ය ගවේෂකයෙකු වූ සැමුවෙල් බේකර් වෙත හමුදා ගවේෂණයක් යැවීය. උතුරු උගන්ඩාවේ මායිම්, එහි වහල් වෙළඳාම මර්දනය කිරීම සහ වාණිජ්යය සහ "ශිෂ්ටාචාරය" සඳහා මාර්ගය විවෘත කිරීමේ අරමුණින්. ඔහුගේ පසුබැසීම තහවුරු කර ගැනීම සඳහා මංමුලා සහගත සටනක නිරත වීමට සිදු වූ බේකර්ට බන්යොරෝ විරුද්ධ විය. බේකර් ප්රතිරෝධය ද්රෝහී ක්රියාවක් ලෙස සැලකූ අතර, ඔහු පොතක බැන්යෝරෝ හෙළා දුටුවේය (ඉස්මායිලියා - වහල් වෙළඳාම මර්දනය කිරීම සඳහා මධ්යම අප්රිකාවට කළ ගවේෂණයේ ආඛ්යානය, ඉස්මයිල්, ඊජිප්තුවේ ඛාඩිව් (1874) විසින් සංවිධානය කරන ලදී)[9] එය බ්රිතාන්යයේ බහුලව කියවන ලදී. පසුව, බුන්යෝරෝ රාජධානියට එරෙහිව නැඹුරුවක් ඇතිව බ්රිතාන්යයන් උගන්ඩාවට පැමිණ බුගන්ඩා රාජධානියේ පැත්ත ගත්හ. මෙය අවසානයේ බුන්යෝරෝට බ්රිතාන්යයන්ගෙන් ත්යාගයක් ලෙස බුගන්ඩා වෙත ලබා දුන් එහි භූමියෙන් අඩක් අහිමි වනු ඇත. "අහිමි වූ ප්රාන්ත" වලින් දෙකක් නිදහසින් පසු බුන්යොරෝ වෙත ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය කරන ලදී.

1860 ගණන් වලදී, අරාබිවරුන් උතුරේ සිට බලපෑම් කිරීමට උත්සාහ කරන අතර, නයිල්[10] මූලාශ්රය සොයන බ්රිතාන්ය ගවේෂකයෝ උගන්ඩාවට පැමිණියහ. ඔවුන් අනුගමනය කළේ 1877 දී බුගන්ඩා රාජධානියට පැමිණි බ්රිතාන්ය ඇංග්ලිකන් මිෂනාරිවරුන් සහ 1879 දී ප්රංශ කතෝලික මිෂනාරිවරුන් ය. මෙම තත්ත්වය 1885 දී උගන්ඩාවේ දිවි පිදූවන්ගේ මරණයට හේතු විය - I වන මුටීසා සහ ඔහුගේ රාජ සභාව හැරවීමෙන් පසුව, සහ ඔහුගේ ක්රිස්තියානි විරෝධී පුත් ම්වංගගේ අනුප්රාප්තිය.[11]

බ්රිතාන්ය රජය විසින් 1888 වසරේ සිට කලාපයේ වෙළඳ ගිවිසුම් සඳහා සාකච්ඡා කිරීමට ඉම්පීරියල් බ්රිතාන්ය නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකා සමාගම (IBEAC) වරලත් කරන ලදී.[12]

1886 සිට, බුගන්ඩාවේ ආගමික යුද්ධ මාලාවක් පැවති අතර, මුලින් මුස්ලිම්වරුන් සහ ක්රිස්තියානින් අතර සහ පසුව, 1890 සිට, "බා-ඉංග්ලේසා" රෙපරමාදු භක්තිකයන් සහ "බා-ෆ්රාන්සා" කතෝලිකයන් අතර, ඔවුන් පෙලගැසී සිටි අධිරාජ්ය බලවතුන්ගේ කන්ඩායම් අතර විය.[13][14] සිවිල් නොසන්සුන්තා සහ මූල්ය බර නිසා, IBEAC කියා සිටියේ තමන්ට කලාපය තුළ "ඔවුන්ගේ රැකියාව පවත්වාගෙන යාමට" නොහැකි වූ බවයි.[15] බ්රිතාන්ය වාණිජ අවශ්යතා නයිල් නදියේ වෙළඳ මාර්ගය ආරක්ෂා කිරීම සඳහා දැඩි වූ අතර, එය 1894 දී උගන්ඩා ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශය නිර්මාණය කිරීම සඳහා බුගන්ඩාව සහ යාබද ප්රදේශ ඈඳා ගැනීමට බ්රිතාන්ය රජය පොළඹවන ලදී.[12][16]

උගන්ඩා ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශය (1894–1962)[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාවේ ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශය 1894 සිට 1962 දක්වා බ්රිතාන්ය අධිරාජ්යයේ ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශයක් විය. 1893 දී, ඉම්පීරියල් බ්රිතාන්ය නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු සමාගම ප්රධාන වශයෙන් බුගන්ඩා රාජධානියෙන් සමන්විත භූමි ප්රදේශයේ පරිපාලන අයිතිය බ්රිතාන්ය රජයට පවරන ලදී. උගන්ඩාවේ අභ්යන්තර ආගමික යුද්ධ නිසා උගන්ඩාව බංකොලොත් භාවයට ඇද දැමීමෙන් පසුව IBEAC උගන්ඩාවේ පාලනය අත්හැරියේය.[17]

1894 දී, උගන්ඩා ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශය පිහිටුවන ලද අතර, අනෙකුත් රාජධානි (1900 දී ටෝරෝ,[18] 1901 දී ඇන්කෝල් සහ 1933 දී බුන්යෝරෝ[19]) සමඟ තවත් ගිවිසුම් අත්සන් කිරීමෙන් බුගන්ඩා දේශසීමාවෙන් ඔබ්බට ප්රදේශය ව්යාප්ත කරන ලදී. එය දළ වශයෙන් වර්තමාන උගන්ඩාවට අනුරූප වේ.[20]

ප්රදේශය අසල්වැසි කෙන්යාව වැනි යටත් විජිතයක් බවට පත් කළාට වඩා ආරක්ෂක රාජ්යයේ තත්ත්වය උගන්ඩාවට සැලකිය යුතු වෙනස් ප්රතිවිපාක ඇති කළේ, උගන්ඩාව පූර්ණ යටත් විජිත පාලනයක් යටතේ වෙනත් ආකාරයකින් සීමා වීමට ඉඩ තිබූ ස්වයං පාලන උපාධියක් රඳවාගෙන සිටින තාක් දුරට ය.[21]

1890 ගණන් වලදී, උගන්ඩාවේ දුම්රිය මාර්ගය ඉදිකිරීම සඳහා ගිවිසුම්ගත කම්කරු කොන්ත්රාත්තු යටතේ බ්රිතාන්ය ඉන්දියාවේ කම්කරුවන් 32,000ක් නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාවට බඳවා ගන්නා ලදී.[22] දිවි ගලවා ගත් බොහෝ ඉන්දියානුවන් ආපසු සිය රට බලා ගිය නමුත් 6,724 ක් රේඛාව අවසන් වූ පසු නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකාවේ රැඳී සිටීමට තීරණය කළහ.[23] පසුව, ඇතැමෙක් වෙළෙන්දන් බවට පත් වූ අතර කපු ජින් කිරීම සහ සාර්ටෝරියල් සිල්ලර වෙළඳාම පාලනය කර ගත්හ.[24]

1900 සිට 1920 දක්වා උගන්ඩාවේ දකුණු ප්රදේශයේ, වික්ටෝරියා විලෙහි උතුරු වෙරළ ආශ්රිතව හටගත් නිදිමත රෝග වසංගතයක් හේතුවෙන් පුද්ගලයන් 250,000කට වැඩි පිරිසක් මිය ගියහ.[25]

දෙවන ලෝක සංග්රාමය උගන්ඩාවේ යටත් විජිත පරිපාලනය විසින් රජුගේ අප්රිකානු රයිෆල් හමුදාවට සේවය කිරීම සඳහා සොල්දාදුවන් 77,143 ක් බඳවා ගැනීමට දිරිමත් කරන ලදී. ඔවුන් බටහිර කාන්තාර ව්යාපාරය, අබිසීනියානු ව්යාපාරය, මැඩගස්කර සටන සහ බුරුම ව්යාපාරයේ ක්රියා කරන ආකාරය දැකගත හැකි විය.

ස්වාධීනත්වය (1962 සිට 1965)[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාව 1962 ඔක්තෝම්බර් 9 වන දින එක්සත් රාජධානියෙන් නිදහස ලබා ගත්තේ II වන එලිසබෙත් රැජින රාජ්ය නායකයා සහ උගන්ඩාවේ රැජින ලෙසය. 1963 ඔක්තෝම්බර් මාසයේදී උගන්ඩාව ජනරජයක් බවට පත් වූ නමුත් පොදුරාජ්ය මණ්ඩලීය ජාතීන්ගේ සාමාජිකත්වය පවත්වා ගෙන ගියේය.

නිදහසින් පසු 1962 පැවති පළමු මැතිවරණය උගන්ඩා මහජන කොංග්රසය (UPC) සහ කබක යක්කා (KY) අතර සන්ධානයකින් ජයග්රහණය කරන ලදී. UPC සහ KY විධායක අගමැති ලෙස මිල්ටන් ඔබෝට් සමඟින් නිදහසින් පසු පළමු රජය පිහිටවූ අතර බුගන්ඩා කබකා (රජු) II වන එඩ්වඩ් මුටීසා බොහෝ දුරට චාරිත්රානුකූල ජනාධිපති තනතුර දරයි.[26][27]

බුගන්ඩා අර්බුදය (1962-1966)[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාවේ නිදහසින් පසු ආසන්න වසර තුළ මධ්යම රජය සහ විශාලතම ප්රාදේශීය රාජධානිය - බුගන්ඩාව අතර සම්බන්ධය ආධිපත්යය දැරීය.[28]

බ්රිතාන්යයන් උගන්ඩා ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශය නිර්මාණය කළ මොහොතේ සිට, ඒකීය රාජ්ය රාමුව තුළ විශාලතම රාජාණ්ඩුව කළමනාකරණය කරන්නේ කෙසේද යන ගැටලුව සැමවිටම ගැටලුවක් විය. යටත් විජිත ආණ්ඩුකාරවරුන් වැඩ කරන සූත්රයක් ඉදිරිපත් කිරීමට අසමත් විය. මධ්යම ආන්ඩුව සමග ඇති සම්බන්ධය පිලිබඳ බුගන්ඩාගේ නොසැලකිලිමත් ආකල්පය නිසා මෙය තවත් සංකීර්ණ විය. බුගන්ඩා කිසි විටෙකත් ස්වාධීනත්වය අපේක්ෂා නොකළ නමුත් බ්රිතාන්යයන් ඉවත්ව යන විට ආරක්ෂක ප්රදේශය තුළ ඇති අනෙකුත් යටත්වැසියන්ට වඩා වැඩි වරප්රසාද හෝ විශේෂ තත්වයක් සහතික කරන ලිහිල් විධිවිධානයක් සමඟ සැපපහසු වූ බවක් පෙනෙන්නට තිබුණි. මෙය බ්රිතාන්ය යටත් විජිත බලධාරීන් සහ නිදහස ලැබීමට පෙර බුගන්ඩා අතර පැවති සතුරුකම් වලින් අර්ධ වශයෙන් සාක්ෂි දරයි.[29]

බුගන්ඩාව තුළ, කබකා අධිපති රජෙකු ලෙස සිටීමට කැමති අය සහ නවීන ලෞකික රාජ්යයක් නිර්මාණය කිරීම සඳහා උගන්ඩාවේ සෙසු ප්රදේශ සමඟ එක්වීමට කැමති අය අතර බෙදීම් ඇති විය. මෙම භේදයේ ප්රතිඵලය වූයේ බුගන්ඩාව පදනම් කරගත් ප්රමුඛ පක්ෂ දෙකක් - කබක යක්කා (කබක පමණි) KY සහ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී පක්ෂය (DP) කතෝලික පල්ලියේ මුල් බැස ගැනීමයි. විශේෂයෙන්ම පශ්චාත් යටත් විජිත පාර්ලිමේන්තුව සඳහා පළමු මැතිවරණය ළං වන විට මෙම පක්ෂ දෙක අතර තිත්තකම අතිශයින් උග්ර විය. කබකා විශේෂයෙන්ම DP නායක බෙනඩික්ටෝ කිවානුකාට අකමැති විය.[30]

බුගන්ඩාවෙන් පිටත, උතුරු උගන්ඩාවේ මෘදු දේශපාලකයෙකු වන මිල්ටන් ඔබෝටේ, උගන්ඩා මහජන කොංග්රසය (UPC) පිහිටුවීම සඳහා බුගන්ඩා නොවන දේශපාලනඥයන්ගේ සන්ධානයක් ගොඩනඟා ගෙන තිබුණි. UPC එහි හදවතේ ආධිපත්යය දැරුවේ බුගන්ඩාගේ විශේෂ තත්ත්වයට අනුග්රහය දක්වන කලාපීය අසමානතාවය ලෙස ඔවුන් දුටු දේ නිවැරදි කිරීමට අවශ්ය දේශපාලනඥයන් විසිනි. මෙය බුගන්ඩාවෙන් පිටත සිට සැලකිය යුතු සහයෝගයක් ලබා ගත්තේය. පක්ෂය කෙසේ වෙතත් ලිහිල් සන්ධානයක් ලෙස පැවති නමුත්, ඔබෝටේ ෆෙඩරල් සූත්රයක් මත පදනම් වූ පොදු පදනමක් බවට සාකච්චා කිරීමට විශාල දක්ෂතාවයක් පෙන්නුම් කළේය.[31]

නිදහසේ දී බුගන්ඩා ප්රශ්නය නොවිසඳී පැවතුනි. උගන්ඩාව යනු පාර්ලිමේන්තුවේ පැහැදිලි බහුතරයක් සහිත ප්රමුඛ දේශපාලන පක්ෂයකින් තොරව නිදහස ලබා ගත් යටත් විජිත ප්රදේශ කිහිපයෙන් එකකි. නිදහසට පෙර පැවති මැතිවරනයේදී, UPC බුගන්ඩාවේ කිසිදු අපේක්ෂකයෙකු ඉදිරිපත් නොකළ අතර සෘජුවම තේරී පත් වූ ආසන 61 න් 37 ක් දිනා ගත්තේය (බුගන්ඩාවෙන් පිටත). ඩීපී බුගන්ඩාවෙන් පිටත ආසන 24 ක් දිනා ගත්තේය. බුගන්ඩාවට ලබා දී ඇති "විශේෂ තත්ත්වය" යන්නෙන් අදහස් කළේ බුගන්ඩා ආසන 21 බුගන්ඩා පාර්ලිමේන්තුවට - ලුකික්කෝ සඳහා වන මැතිවරණ පිළිබිඹු කරමින් සමානුපාතික නියෝජනයෙන් තේරී පත් වූ බවයි. KY ආසන 21 ම දිනා ගනිමින් DP ට වඩා විශිෂ්ට ජයග්රහණයක් ලබා ගත්තේය.

1964 අවසානයේ පාර්ලිමේන්තුවේ DP නායක බැසිල් කීසා බටරිංගයා තවත් මන්ත්රීවරුන් පස් දෙනෙකු සමඟ පාර්ලිමේන්තු තට්ටුව තරණය කළ විට UPC ඉහළ මට්ටමකට පැමිණියේය, DP ට ආසන නවයක් පමණක් ඉතිරි විය. ඔවුන්ගේ නායක බෙනඩික්ටෝ කිවානුකා කබකා කෙරෙහි දක්වන සතුරුකම KY සමග සම්මුතියකට පැමිණීමට බාධාවක් වීම ගැන DP මන්ත්රීවරුන් විශේෂයෙන් සතුටු වූයේ නැත.[32] UPC සමග විධිමත් සභාගය තවදුරටත් ශක්ය නොවන බව වටහාගත් KY සාමාජිකයින් 10 දෙනෙකු බිම තරණය කළ විට, පලායාමේ ජලගැල්ම ගංවතුරක් බවට පත් විය. රට පුරා ඔබෝටේ ගේ ප්රචලිත කතා ඔහු ඉදිරියෙන් පැතිර ගිය අතර, UPC පැවැත් වූ සෑම ප්රාදේශීය මැතිවරණයක්ම පාහේ ජයග්රහණය කරමින් බුගන්ඩාවෙන් පිටත සියලුම දිස්ත්රික් සභා සහ ව්යවස්ථාදායකයන්හි සිය පාලනය වැඩි කර ගනිමින් සිටියේය.[33] කබකාගේ ප්රතිචාරය ගොළු විය - බොහෝ විට ඔහුගේ චාරිත්රානුකූල භූමිකාවෙන් සහ රටෙහි ඔහුගේ කොටසෙහි සංකේතවාදයෙන් සෑහීමට පත් විය හැකිය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, ඔහුගේ මාලිගාව තුළ විශාල බෙදීම් ද ඇති වූ අතර එමඟින් ඔබෝටේට එරෙහිව ඵලදායී ලෙස ක්රියා කිරීමට ඔහුට අපහසු විය. උගන්ඩාව ස්වාධීන වූ කාලය වන විට, බුගන්ඩාව "විවාදාත්මක සමාජ සහ දේශපාලන බලවේග සමඟ බෙදී ගිය නිවසක් විය"[34] කෙසේ වෙතත් UPC තුළ ගැටලු ඇති විය. එහි තරාතිරම වැඩි වූ විට, වාර්ගික, ආගමික, ප්රාදේශීය සහ පුද්ගලික අවශ්යතා පක්ෂය දෙදරීමට පටන් ගත්තේය. එහි මධ්යම හා ප්රාදේශීය ව්යුහය තුළ කන්ඩායම් ගැටුම්වල සංකීර්ණ අනුපිළිවෙලක් තුළ පක්ෂයේ පෙනෙන ශක්තිය ඛාදනය විය. තවද 1966 වන විට UPC එක දෙකඩ විය. DP සහ KY වෙතින් පාර්ලිමේන්තු බිම තරණය කළ නවකයින් නිසා ගැටුම් තවත් තීව්ර විය.[35]

UPC නියෝජිතයන් ඔවුන්ගේ නියෝජිත සමුළුව සඳහා 1964 දී Gulu වෙත පැමිණියහ. ඔබ්ටේට තම පක්ෂයේ පාලනය ගිලිහී යන ආකාරය පිළිබඳ පළමු ප්රදර්ශනය වූයේ මෙහිදීය. පක්ෂයේ මහලේකම්වරයාගේ සටන නව මධ්යස්ථ අපේක්ෂක ග්රේස් ඉබිංගිරා සහ රැඩිකල් ජෝන් කකෝන්ගේ අතර තියුණු තරගයක් විය. ඉබිංගිර පසුව UPC තුළ ඔබෝටේ විරෝධයේ සංකේතය බවට පත් විය. බුගන්ඩා සහ මධ්යම රජය අතර අර්බුදයට තුඩු දුන් පසුකාලීන සිදුවීම් දෙස බලන විට මෙය වැදගත් සාධකයකි. UPC පිටත සිටින අයට (KY ආධාරකරුවන් ඇතුළුව), මෙය ඔබෝටේ අවදානමට ලක්ව ඇති බවට ලකුණක් විය. UPC යනු සමෝධානික ඒකකයක් නොවන බව දැඩි නිරීක්ෂකයෝ වටහා ගත්හ.[36]

UPC-KY සන්ධානයේ බිඳවැටීම බුගන්ඩාගේ "විශේෂ තත්ත්වය" ගැන ඔබෝටේ සහ අනෙකුත් අය තුළ තිබූ අතෘප්තිය විවෘතව හෙළිදරව් විය. 1964 දී, ඔවුන් කබකාගේ යටත්වැසියන් නොවන බවට විශාල බුගන්ඩා රාජධානියේ සමහර ප්රදේශවලින් කළ ඉල්ලීම්වලට රජය ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීය. යටත් විජිත පාලනයට පෙර, බුගන්ඩාව අසල්වැසි බුන්යෝරෝ රාජධානිය විසින් ප්රතිවාදී විය. බුගන්ඩා විසින් බුන්යොරෝ හි කොටස් අත්පත් කර ගෙන ඇති අතර බ්රිතාන්ය යටත් විජිතවාදීන් බුගන්ඩා ගිවිසුම් මගින් මෙය විධිමත් කර ඇත. "අහිමි ප්රාන්ත" ලෙස හැඳින්වෙන, මෙම ප්රදේශවල ජනතාව නැවත බුන්යොරෝ හි කොටසක් වීමට කැමති විය. ඔබෝටේ ජනමත විචාරණයකට ඉඩ දීමට තීරණය කළ අතර එය කබකා සහ බුගන්ඩාවේ සෙසු බොහෝ දෙනා කෝපයට පත් කළේය. කබකා ඡන්දයට බලපෑම් කිරීමට උත්සාහ කළද ප්රාන්තවල පදිංචිකරුවන් බුන්යෝරෝ වෙත ආපසු යාමට ඡන්දය දුන්හ.[37] ජනමත විචාරණයෙන් පරාජය වූ KY, Bunyoro වෙත ප්රාන්ත සම්මත කිරීමේ පනතට විරුද්ධ වූ අතර, එමඟින් UPC සමඟ ඇති සන්ධානය අවසන් විය.

උගන්ඩා දේශපාලනයේ ගෝත්රික ස්වභාවය රජය තුළ ද ප්රකාශ වෙමින් තිබිණි. මීට පෙර ජාතික පක්ෂයක්ව සිටි UPC ගෝත්රික රේඛාවන් ඔස්සේ කැඩී යාමට පටන් ගත්තේ ඉබිංගිරා UPC තුළ ඔබෝටේට අභියෝග කිරීමත් සමඟය. ආර්ථික හා සමාජීය ක්ෂේත්රවල ප්රකටව තිබූ "උතුර/දකුණු" වාර්ගික භේදය දැන් දේශපාලනයේ මුල් බැස ඇත. ඔබෝටේ ප්රධාන වශයෙන් උතුරේ දේශපාලනඥයින් වටකරගත් අතර, පසුව ඔහු සමඟ අත්අඩංගුවට ගෙන සිරගත කරන ලද ඉබිංගිරාගේ ආධාරකරුවන් ප්රධාන වශයෙන් දකුණේ අය වූහ. කාලයාගේ ඇවෑමෙන්, කන්ඩායම් දෙක වාර්ගික ලේබල් ලබා ගත්හ - "බන්ටු" (ප්රධාන වශයෙන් දකුණු ඉබිංගිරා කන්ඩායම) සහ "නිලෝටික්" (ප්රධාන වශයෙන් උතුරු ඔබෝටේ කන්ඩායම). ඉබිංගිරාට සහය දුන් ප්රධාන වශයෙන් බන්ටු ඇමතිවරුන් ඔබොටේ අත්අඩංගුවට ගෙන සිරගත කිරීමත් සමඟ රජය බන්ටු සමඟ යුද්ධයක යෙදී සිටින බවට වූ මතය තවදුරටත් වර්ධනය විය.[38]

මෙම ලේබල් ඉතා ප්රබල බලපෑම් දෙකක් මිශ්රණයට ගෙන එන ලදී. පළමු බුගන්ඩා - බුගන්ඩාවේ ජනතාව බන්ටු වන අතර එබැවින් ස්වභාවිකවම ඉබිංගිරා කන්ඩායමට පෙලගැසී ඇත. ඉබිංගිර පාර්ශවය මෙම සන්ධානය තව දුරටත් ඉදිරියට ගෙන ගියේ කබක පෙරලීමට ඔබ්ටේට අවශ්ය බවට චෝදනා කරමිනි.[38] ඔවුන් දැන් ඔබෝටේට විරුද්ධ වීමට පෙළ ගැසී සිටියහ. දෙවනුව - ආරක්ෂක හමුදා - බ්රිතාන්ය යටත්විජිතවාදීන් හමුදාව සහ පොලිසිය බඳවාගෙන තිබුණේ උතුරු උගන්ඩාවේ සිට මෙම භූමිකාවන් සඳහා ඔවුන්ගේ යෝග්ය බව වටහා ගත් නිසාය. නිදහසේ දී, හමුදාව සහ පොලිසිය ආධිපත්යය දැරුවේ උතුරු ගෝත්රිකයන් විසිනි - ප්රධාන වශයෙන් නිලෝටික්. ඔවුන් දැන් ඔබෝටේට වඩාත් සම්බන්ධ බවක් දැනෙනු ඇති අතර, ඔහු තම බලය තහවුරු කර ගැනීමට මෙයින් උපරිම ප්රයෝජන ගත්තේය. 1966 අප්රේල් මාසයේදී, ඔබෝටේ විසින් මොරෝටෝ හි නව හමුදා බඳවා ගැනීම් අටසියයක් සමත් වූ අතර, ඔවුන්ගෙන් සියයට හැත්තෑවක් උතුරු ප්රදේශයෙන් පැමිණි අයයි.[39]

එකල මධ්යම ආන්ඩුව සහ ආරක්ෂක හමුදා "උතුරු" ආධිපත්යය දැරීමේ ප්රවණතාවක් පැවතුනි - විශේෂයෙන් UPC හරහා ජාතික මට්ටමේ රජයේ තනතුරු සඳහා සැලකිය යුතු ප්රවේශයක් ඇති අචෝලි.[40]උ තුරු උගන්ඩාවේ ද බුගන්ඩා විරෝධී හැඟීම්වල විවිධ මට්ටම් ඇති විය, විශේෂයෙන් නිදහසට පෙර සහ පසු රාජධානියේ "විශේෂ තත්ත්වය" සහ මෙම තත්ත්වය සමඟ ලැබුණු සියලු ආර්ථික හා සමාජ ප්රතිලාභ පිළිබඳව. "ඔබෝටේ සිවිල් සේවය සහ හමුදාව හරහා සැලකිය යුතු සංඛ්යාවක් උතුරේ වැසියන් මධ්යම ප්රාන්තයට ගෙන ආ අතර උතුරු උගන්ඩාවේ අනුග්රාහක යන්ත්රයක් නිර්මාණය කළේය".[40] කෙසේ වෙතත්, "බන්ටු" සහ "නිලෝටික්" ලේබල් දෙකම සැලකිය යුතු අපැහැදිලි භාවයන් නියෝජනය කරයි. උදාහරණයක් ලෙස බන්ටු කාණ්ඩයට බුගන්ඩා සහ බුන්යොරෝ යන දෙකම ඇතුළත් වේ - ඓතිහාසික වශයෙන් කටුක ප්රතිවාදීන්. Nilotic ලේබලයට ලුග්බරා, අචෝලි සහ ලැන්ගි ඇතුළත් වන අතර, ඔවුන් සියල්ලන්ටම උගන්ඩාවේ හමුදා දේශපාලනය පසුව නිර්වචනය කිරීමට තිත්ත එදිරිවාදිකම් ඇත. මෙම අපැහැදිලිකම් තිබියදීත්, මෙම සිදුවීම් නොදැනුවත්වම උගන්ඩා දේශපාලනයට යම් දුරකට බලපෑම් කරන උතුරු/දකුණු දේශපාලන භේදය ඉදිරියට ගෙන ආවේය.

UPC ඛණ්ඩනය දිගටම සිදු වූයේ විරුද්ධවාදීන් Obote ගේ දුර්වලතාවය දැනගත් බැවිනි. UPC බොහෝ සභාවල ආධිපත්යය දැරූ ප්රාදේශීය මට්ටමින් අතෘප්තිය වත්මන් සභා නායකයින්ට අභියෝග කිරීමට පටන් ගත්තේය. ඔබෝටේ ගේ උපන් දිස්ත්රික්කයේ පවා, 1966 දී ප්රාදේශීය දිස්ත්රික් කවුන්සිලයේ ප්රධානියා නෙරපා හැරීමට උත්සාහ කරන ලදී. UPC සඳහා වඩාත් කනස්සල්ලට කරුණක් වූයේ 1967 දී මීළඟ ජාතික මැතිවරනය එළඹීමයි - සහ KY ගේ සහාය නොමැතිව (දැන් ඉඩ ඇති) DP ට පිටුපෑවා), සහ UPC තුල වැඩෙන කන්ඩායම්වාදය, UPC මාස කිහිපයකින් බලයෙන් ඉවත් වීමේ සැබෑ හැකියාව විය.

1966 මුල් භාගයේ දී බුගන්ඩාවෙන් පිටත ව්යාප්ත කිරීමට KY දරන ඕනෑම උත්සාහයක් අවහිර කළ නව පාර්ලිමේන්තු පනතක් සමඟ ඔබෝටේ KY පසුපස ගියේය. KY ඔවුන්ගේ ඉතිරිව සිටින මන්ත්රීවරුන් කිහිප දෙනාගෙන් කෙනෙකු වන මාරාන්තික රෝගාතුර වූ ඩවුඩි ඔචියං හරහා පාර්ලිමේන්තුවේදී ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීමට පෙනී සිටියේය. ඔචියං උත්ප්රාසජනක විය - උතුරු උගන්ඩාවේ සිට වුවද, ඔහු KY නිලයෙන් ඉහළට ගොස් බුගන්ඩාවේ විශාල ඉඩම් හිමිකම් ලබා දුන් කබකාගේ සමීප විශ්වාසවන්තයෙකු බවට පත්විය. ඔබෝටේගේ හමුදා මාණ්ඩලික ප්රධානී කර්නල් ඉඩි අමීන් විසින් සංවිධානය කරන ලද කොංගෝවෙන් ඇත් දළ සහ රත්රං නීතිවිරෝධී ලෙස කොල්ලකෑම ගැන ඔබෝටේ පාර්ලිමේන්තුවට නොපැමිණීමේදී හෙළි කළේය. ඔහු තවදුරටත් චෝදනා කළේ ඔබෝටේ, ඕනාමා සහ නෙයිකොන් යන සියලු දෙනාම මෙම යෝජනා ක්රමයෙන් ප්රතිලාභ ලැබූ බවයි.[41] අමීන් වාරණය කිරීමට සහ ඔබෝටේගේ මැදිහත්වීම විමර්ශනය කිරීමට යෝජනාවකට පක්ෂව පාර්ලිමේන්තුව විශාල වශයෙන් ඡන්දය ප්රකාශ කළේය. මෙය රජය දෙදරා ගිය අතර රට තුළ ආතතීන් ඇති කළේය.

KY, KY, ඉබිංගිර සහ බුගන්ඩා හි අනෙකුත් ඔබෝටේ විරෝධී කොටස්වල පිටුබලය ඇතැයි විශ්වාස කරන කන්ඩායමක් විසින් ගොඩ්ෆ්රි බිනයිසා (නීතිපති) නෙරපා හරින ලද UPC බුගන්ඩා සමුළුවේදී KY විසින් ඔබෝටේ ට තම පක්ෂය තුලින්ම අභියෝග කිරීමේ හැකියාව තවදුරටත් පෙන්නුම් කළේය.[34] ඔබෝටේගේ ප්රතිචාරය වූයේ කැබිනට් රැස්වීමකදී ඉබිංගිරා සහ අනෙකුත් අමාත්යවරුන් අත්අඩංගුවට ගෙන 1966 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේදී විශේෂ බලතල ලබා ගැනීමයි. 1966 මාර්තු මාසයේදී ඔබෝටේ ජනාධිපති සහ උප සභාපති කාර්යාල නොපවත්වන බව ප්රකාශ කළේය. ඔබෝටේ අමීන්ට වැඩි බලයක් ද ලබා දුන්නේය - විවාහය හරහා බුගන්ඩා සමඟ සබඳතා පැවැත්වූ පෙර හිමිකරුට (ඔපොලොට්) වඩා හමුදාපති තනතුර ඔහුට ලබා දීම (සමහර විට ඔපොලොට් කබකාට එරෙහිව හමුදා ක්රියාමාර්ග ගැනීමට අකමැති වනු ඇතැයි විශ්වාස කරයි). ඔබෝටේ ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාව අහෝසි කර මාස කිහිපයකින් පැවැත්වීමට නියමිත මැතිවරණ ඵලදායී ලෙස අත්හිටුවා ඇත. අමීන් කුමන්ත්රණයක් සැලසුම් කරන බවට පැතිර යන කටකතාවලින් පසුව කබකා විසින් ගවේෂණය කළ බව පෙනෙන විදේශීය හමුදා ඉල්ලා සිටීම ඇතුළු විවිධ වැරදි සම්බන්ධයෙන් කබකාට චෝදනා කිරීමට ඔබෝටේ රූපවාහිනියෙන් සහ ගුවන් විදුලියෙන් ගියේය. ඔබෝටේ අනෙකුත් ක්රියාමාර්ග අතර නිවේදනය කරමින් කබකගේ අධිකාරිය තවදුරටත් බිඳ දැමීය:

- ෆෙඩරල් ඒකක සඳහා ස්වාධීන රාජ්ය සේවා කොමිෂන් සභා අහෝසි කිරීම. මෙමගින් බුගන්ඩාවේ සිවිල් සේවකයන් පත්කිරීමේ කබකාගේ බලතල ඉවත් කරන ලදී.

- බුගන්ඩා මහාධිකරණය අහෝසි කිරීම - කබකාට තිබූ ඕනෑම අධිකරණ අධිකාරියක් ඉවත් කිරීම.

- බුගන්ඩා මූල්ය කළමනාකරණය තවදුරටත් මධ්යම පාලනය යටතට ගෙන ඒම.

- බුගන්ඩා ප්රධානීන් සඳහා ඉඩම් අහෝසි කිරීම. ඉඩම් කබකගේ යටත්වැසියන් කෙරෙහි බලයේ ප්රධාන මූලාශ්රවලින් එකකි.

බුගන්ඩා සහ මධ්යම රජය අතර සංදර්ශනයක් සඳහා දැන් රේඛා ඇඳ තිබේ. සම්මුතියෙන් මෙය වළක්වා ගත හැකිව තිබුණා දැයි ඉතිහාසඥයන් තර්ක කළ හැකිය. ඔබෝට දැන් නිර්භීත බවක් දැනුණු අතර කබකා දුර්වල බව දුටු නිසා මෙය කළ නොහැක්කකි. ඇත්ත වශයෙන්ම, වසර හතරකට පෙර ජනාධිපතිකම පිළිගෙන යූපීසීයට පක්ෂව සිටීමෙන්, කබකා තම ජනතාව දෙකඩ කර අනෙකාට එරෙහිව එකෙකුගේ පැත්ත ගෙන ඇත. බුගන්ඩාගේ දේශපාලන ආයතන තුළ, ආගම හා පෞද්ගලික අභිලාෂයන් විසින් මෙහෙයවන ලද එදිරිවාදිකම් නිසා ආයතන අකාර්යක්ෂම වූ අතර මධ්යම රජයේ පියවරයන්ට ප්රතිචාර දැක්වීමට නොහැකි විය. තම සම්ප්රදායික ප්රතිලාභ පවත්වාගෙන යන තාක් කල් සිදුවෙමින් පවතින දේ ගැන දෙගිඩියාවෙන් සිටි සම්ප්රදායිකවාදීන් මෙන් නොව, නව පශ්චාත්-නිදහස් දේශපාලනය වඩා හොඳින් අවබෝධ කරගත් තරුණ බුගන්ඩා දේශපාලකයන්ගේ උපදෙස්වලට කබකා බොහෝ විට වෙන්ව සහ ප්රතිචාර නොදක්වන ලෙස සැලකේ. කබක නව සම්ප්රදායිකවාදීන්ට අනුග්රහය දැක්වීය.[42]

1966 මැයි මාසයේදී කබකා ඔහුගේ පියවර ගත්තේය. ඔහු විදේශ ආධාර ඉල්ලා සිටි අතර, බුගන්ඩා පාර්ලිමේන්තුව උගන්ඩා රජයට බුගන්ඩාවෙන් (කම්පාලා අගනුවර ඇතුළුව) ඉවත් විය යුතු යැයි ඉල්ලා සිටියේය. ඊට ප්රතිචාර වශයෙන් ඔබෝතේ ඉඩි අමීන්ට කබකගේ මාලිගාවට පහර දෙන ලෙස නියෝග කළේය. කබකගේ මාලිගය සඳහා වූ සටන දරුණු විය - කබකගේ ආරක්ෂකයින් බලාපොරොත්තු වූවාට වඩා වැඩි ප්රතිරෝධයක් ඇති කළේය. බ්රිතාන්යයන් විසින් පුහුණු කරන ලද කපිතාන් - කබකා සන්නද්ධ මිනිසුන් 120ක් පමණ සමග ඉඩි අමීන්ව පැය දොළහක් බොක්කෙහි තබා ගත්හ.[43] හමුදාව බර තුවක්කු කැඳවා මාලිගාව අත්පත් කර ගැනීමත් සමඟ අවසන් වූ සටනේදී මිනිසුන් 2,000 ක් පමණ මිය ගිය බව ගණන් බලා ඇත. බුගන්ඩාවේ අපේක්ෂිත ගම්බද කැරැල්ල ක්රියාත්මක නොවූ අතර පැය කිහිපයකට පසු ඔබෝටේ ඔහුගේ ජයග්රහණය රස විඳීමට මාධ්යවේදීන් හමු විය. කබකා මාලිගාවේ බිත්ති මතින් පැන ගිය අතර ආධාරකරුවන් විසින් ලන්ඩනයට පිටුවහල් කරන ලදී. වසර තුනකට පසු ඔහු එහිදී මිය ගියේය.

1966-1971 (කුමන්ත්රණයට පෙර)[සංස්කරණය]

1966 දී, ඔබෝටේ ප්රමුඛ රජය සහ මුටීසා රජු අතර ඇති වූ බල අරගලයකින් පසු, ඔබෝටේ ව්යවස්ථාව අත්හිටුවා චාරිත්රානුකූල ජනාධිපති සහ උප සභාපති ඉවත් කළේය. 1967 දී නව ආණ්ඩුක්රම ව්යවස්ථාවකින් උගන්ඩාව ජනරජයක් ලෙස ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලද අතර සම්ප්රදායික රාජධානි අහෝසි කරන ලදී. ඔබෝටේ ජනාධිපතිවරයා ලෙස ප්රකාශයට පත් කරන ලදී.[11]

1971 (කුමන්ත්රණයෙන් පසු) –1979 (අමීන් පාලනයේ අවසානය)[සංස්කරණය]

1971 ජනවාරි 25 හමුදා කුමන්ත්රණයකින් පසු ඔබෝටේ බලයෙන් නෙරපා හරින ලද අතර ජෙනරාල් ඉඩි අමීන් රටේ පාලනය අල්ලා ගත්තේය. අමීන් උගන්ඩාව ආඥාදායක ලෙස පාලනය කළේ හමුදාවේ සහාය ඇතිව ඉදිරි වසර අට තුළය.[44] ඔහු තම පාලනය පවත්වා ගැනීම සඳහා රට තුළ සමූහ ඝාතන සිදු කළේය. ඔහුගේ පාලන සමයේදී උගන්ඩා ජාතිකයන් 80,000-500,000ක් පමණ මිය ගිය බව ගණන් බලා ඇත.[45] ඔහුගේ ම්ලේච්ඡ ක්රියා පසෙකලා, ඔහු ව්යවසායක ඉන්දියානු සුළුතරය උගන්ඩාවෙන් බලහත්කාරයෙන් ඉවත් කළේය.[46] 1976 ජූනි මාසයේදී පලස්තීන ත්රස්තවාදීන් එයාර් ෆ්රාන්ස් ගුවන් යානයක් පැහැරගෙන එන්ටෙබේ ගුවන් තොටුපළට ගොඩ බස්වන ලෙස බල කළේය. ඊශ්රායල කමාන්ඩෝ ප්රහාරයකින් දින දහයකට පසු ඔවුන් බේරා ගන්නා තෙක් මුලින් යානයේ සිටි මගීන් 250 න් සියයක් ප්රාණ ඇපකරුවන් ලෙස තබා ගන්නා ලදී.[47] 1979 දී උගන්ඩා-ටැන්සානියා යුද්ධයෙන් පසු අමීන්ගේ පාලනය අවසන් වූ අතර, උගන්ඩාවේ පිටුවහල් කරන ලද ටැන්සානියානු හමුදා උගන්ඩාව ආක්රමණය කළෝය.

1979-වර්තමානය[සංස්කරණය]

1980 දී, උගන්ඩා බුෂ් යුද්ධය ආරම්භ වූ අතර එහි ප්රතිඵලයක් ලෙස යොවේරි මුසවේනි 1986 ජනවාරි මාසයේ දී ඔහුගේ හමුදා පෙර පාලනය පෙරළා දැමූ දා සිට ජනාධිපති බවට පත් විය.[49]

නිකායික ප්රචණ්ඩත්වය අවම කිරීම සඳහා නිර්මාණය කර ඇති පියවරක් ලෙස උගන්ඩාවේ දේශපාලන පක්ෂ එම වසරේ සිට ඔවුන්ගේ ක්රියාකාරකම් සීමා කරන ලදී. මුසවේනි විසින් ආරම්භ කරන ලද පක්ෂ නොවන "ව්යාපාරය" ක්රමය තුළ දේශපාලන පක්ෂ දිගටම පැවතුනද ඔවුන්ට ක්රියාත්මක කළ හැක්කේ මූලස්ථාන කාර්යාලයක් පමණි. ඔවුන්ට ශාඛා විවෘත කිරීමට, රැස්වීම් පැවැත්වීමට හෝ සෘජුවම අපේක්ෂකයන් ඉදිරිපත් කිරීමට නොහැකි විය (මැතිවරණ අපේක්ෂකයින් දේශපාලන පක්ෂවලට අයත් විය හැකි වුවද). ව්යවස්ථාපිත ජනමත විචාරණයක් 2005 ජූලි මාසයේදී බහු-පක්ෂ දේශපාලනය සඳහා වූ මෙම දහනව වසරක තහනම අවලංගු කරන ලදී.

1993 දී IIවන ජුවාම් පාවුළු පාප් වහන්සේ තම දින 6ක එඬේර චාරිකාවේදී උගන්ඩාවට ගොස් සංහිඳියාව සෙවීමට උගන්ඩාවේ වැසියන්ගෙන් ඉල්ලා සිටියේය. මහා සැමරුම් අතරතුර, ඔහු මියගිය ක්රිස්තියානි ප්රාණ පරිත්යාගිකයින්ට උපහාර දැක්වීය.

1990 දශකයේ මැද භාගයේ සිට අග භාගය දක්වා, බටහිර රටවල් විසින් මුසවේනි අප්රිකානු නායකයින්ගේ නව පරම්පරාවක කොටසක් ලෙස පැසසුමට ලක් විය.[50]

කෙසේ වෙතත්, දෙවන කොංගෝ යුද්ධයේ දී කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජය ආක්රමණය කර එය අත්පත් කර ගැනීමෙන්, 1998 සිට ඇස්තමේන්තුගත මිලියන 5.4 ක් මිය ගිය අතර, අප්රිකාවේ මහා විල් කලාපයේ වෙනත් ගැටුම්වලට සහභාගී වීමෙන් ඔහුගේ ජනාධිපති ධූරය විනාශ වී ඇත. ළමා වහල් සේවය, ඇටැක් සංහාරය සහ අනෙකුත් සමූහ ඝාතන ඇතුළු මනුෂ්යත්වයට එරෙහි අපරාධ රැසකට වරදකරු වූ ලෝඩ්ස් ප්රතිරෝධක හමුදාවට එරෙහි සිවිල් යුද්ධයේ ඔහු වසර ගණනාවක් අරගල කර ඇත. උතුරු උගන්ඩාවේ ගැටුම් හේතුවෙන් දහස් ගණනක් මිය ගොස් මිලියන ගණනක් අවතැන් වී ඇත.[51]

2005 දී පාර්ලිමේන්තුව විසින් ජනාධිපති ධුර කාල සීමාවන් අහෝසි කරන ලදී, එම පියවරට සහය දුන් සෑම මන්ත්රීවරයෙකුටම ඇමරිකානු ඩොලර් 2,000 ක් ගෙවීමට මුසවේනි මහජන මුදල් භාවිතා කළ නිසා යැයි කියනු ලැබේ.[52] ජනාධිපතිවරනය 2006 පෙබරවාරි මාසයේදී පැවැත්විණි. Museveni අපේක්ෂකයින් කිහිප දෙනෙකුට එරෙහිව තරඟ කළ අතර, ඔවුන්ගෙන් වඩාත්ම කැපී පෙනෙන පුද්ගලයා වූයේ කිසා බෙසිග්යේ ය.

2011 පෙබරවාරි 20 දින, උගන්ඩා මැතිවරණ කොමිෂන් සභාව, 2011 පෙබරවාරි 18 වැනි දින පැවති 2011 මැතිවරණයේ ජයග්රාහී අපේක්ෂකයා ලෙස වත්මන් ජනාධිපති යොවේරි කගුටා මුසවේනි ප්රකාශයට පත් කළේය. කෙසේ වෙතත්, විපක්ෂය ප්රතිඵල ගැන සෑහීමකට පත් නොවූ අතර, ඒවා ව්යාජ සහ වංචාවලින් පිරී ඇති බව හෙළා දකිමින්. . නිල ප්රතිඵලවලට අනුව සියයට 68ක ඡන්ද ප්රතිශතයක් ලබා ගනිමින් මුසවේනි ජයග්රහණය කළේය. මෙය පහසුවෙන්ම මුසවේනිගේ වෛද්යවරයා වූ ඔහුගේ ආසන්නතම අභියෝගකරුවා වන බෙසිග්යේ ඉහළින්ම පත් වූ අතර වාර්තාකරුවන්ට පැවසුවේ ඔහු සහ ඔහුගේ ආධාරකරුවන් ප්රතිපලය මෙන්ම මුසවේනිගේ හෝ ඔහු පත් කළ හැකි ඕනෑම පුද්ගලයෙකුගේ අනවරත පාලනය "සැබෑ ලෙසම නිෂ්ප්රභා කරන" බවයි. දූෂිත මැතිවරණ නිසැකවම නීත්යානුකූල නොවන නායකත්වයකට තුඩු දෙනු ඇති බවත්, මෙය විවේචනාත්මකව විග්රහ කිරීම උගන්ඩා ජාතිකයින්ට පැවරී ඇති බවත් Besigye වැඩිදුරටත් පැවසීය. යුරෝපා සංගමයේ මැතිවරණ නිරීක්ෂණ මෙහෙයුම උගන්ඩා මැතිවරණ ක්රියාවලියේ වැඩිදියුණු කිරීම් සහ දෝෂයන් පිළිබඳව වාර්තා කළේය: "මැතිවරණ ප්රචාරක කටයුතු සහ ඡන්ද විමසීමේ දිනය සාමකාමී ආකාරයකින් පවත්වන ලදී. කෙසේ වෙතත්, මැතිවරණ ක්රියාවලිය පිළිගත නොහැකි සංඛ්යාවකට තුඩු දුන් වළක්වා ගත හැකි පරිපාලනමය සහ සැපයුම් අසාර්ථකත්වයන් මගින් විනාශ විය. උගන්ඩාවේ පුරවැසියන්ගේ ඡන්ද බලය අහිමි වීම."[53]

2012 අගෝස්තු මාසයේ සිට, හක්ටිවිස්ට් කණ්ඩායමක් වන Anonymous, සමලිංගික විරෝධී පනත් සම්බන්ධයෙන් උගන්ඩාවේ නිලධාරීන්ට තර්ජනය කර රජයේ නිල වෙබ් අඩවි හැක් කර ඇත.[54] සමහර ජාත්යන්තර පරිත්යාගශීලීන් සමලිංගික විරෝධී පනත් දිගටම පැවතුනහොත් රටට මූල්ය ආධාර කපා හරින බවට තර්ජනය කර ඇත.[55]

ජනාධිපතිගේ පුත්, මුහුසි කයිනෙරුගබා විසින් අනුප්රාප්තිකය සඳහා සැලැස්මක් පිලිබඳ දර්ශක ආතතිය වැඩි කර ඇත.[56][57][58][59]

ජනාධිපති යොවේරි මුසවේනි 1986 සිට රට පාලනය කර ඇති අතර ඔහු 2021 ජනවාරි ජනාධිපතිවරණයේ දී නැවත තේරී පත් විය.[60] නිල ප්රතිඵලවලට අනුව මුසවේනි 58% ක ඡන්ද ප්රතිශතයක් ලබා ගනිමින් මැතිවරණය ජයග්රහණය කළ අතර පොප්ස්ටාර් බවට පත් වූ දේශපාලනඥයෙකු වූ බොබි වයින් 35% ක් ලබා ගත්තේය. පුළුල් වංචා සහ අක්රමිකතා පිලිබඳ චෝදනා හේතුවෙන් විපක්ෂය ප්රතිඵලය අභියෝගයට ලක් කළේය.[61][62] තවත් විපක්ෂයේ අපේක්ෂකයා වූයේ 24 හැවිරිදි ජෝන් කටුම්බාය.[63]

භූගෝලය[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාව අග්නිදිග අප්රිකාවේ 1º S සහ 4º N අක්ෂාංශ අතර සහ 30º E සහ 35º E දේශාංශ අතර පිහිටා ඇත. එහි භූගෝලය ගිනිකඳු කඳු, කඳු සහ විල් වලින් සමන්විත ඉතා විවිධාකාර වේ. රට සාමාන්යයෙන් මුහුදු මට්ටමේ සිට මීටර් 900 ක උසකින් පිහිටා ඇත. උගන්ඩාවේ නැගෙනහිර සහ බටහිර මායිම් දෙකේම කඳු ඇත. රුවෙන්සෝරි කඳුවැටිය උගන්ඩාවේ උසම කඳු මුදුන අඩංගු වන අතර එය ඇලෙක්සැන්ඩ්රා ලෙස නම් කර ඇති අතර එහි විශාලත්වය මීටර් 5,094 කි.

විල් සහ ගංගා[සංස්කරණය]

දිවයිනේ බොහෝ දකුණු ප්රදේශය ලොව විශාලතම විල්වලින් එකක් වන වික්ටෝරියා විලෙහි බලපෑමට ලක්ව ඇති අතර එය බොහෝ දූපත් වලින් සමන්විත වේ. කම්පාලා අගනුවර[64][65][66] සහ එන්ටෙබේ අගනුවර ඇතුළුව මෙම වැව ආසන්නයේ වඩාත් වැදගත් නගර දකුණේ පිහිටා ඇත.[67] කියෝගා විල රට මධ්යයේ පිහිටා ඇති අතර එය පුළුල් වගුරු බිම් වලින් වටවී ඇත.[68]

ගොඩබිම් සහිත වුවද උගන්ඩාවේ විශාල විල් රාශියක් ඇත. වික්ටෝරියා සහ ක්යෝගා විල් වලට අමතරව ඇල්බට් විල, එඩ්වඩ් විල සහ කුඩා ජෝර්ජ් විල ඇත. එය සම්පූර්ණයෙන්ම පාහේ නයිල් ද්රෝණිය තුළ පිහිටා ඇත. වික්ටෝරියා නයිල් ගඟ වික්ටෝරියා විලෙන් කියෝගා විලටත් එතැනින් කොංගෝ දේශ සීමාවේ ඇල්බට් විලටත් ගලා යයි. ඉන්පසු එය උතුරු දෙසට දකුණු සුඩානයට දිව යයි. නැගෙනහිර උගන්ඩාවේ ප්රදේශයක් තුර්කානා විලෙහි අභ්යන්තර ජලාපවහන ද්රෝණියේ කොටසක් වන සුවාම් ගඟෙන් ජලය බැස යයි. උගන්ඩාවේ අන්ත ඊසානදිග කොටස ප්රධාන වශයෙන් කෙන්යාවේ පිහිටි ලොටිකිපි ද්රෝණියට ගලා යයි.[67]

ජෛව විවිධත්වය සහ සංරක්ෂණය[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාවට ජාතික වනෝද්යාන දහයක් ඇතුළුව ආරක්ෂිත ප්රදේශ 60ක් ඇත: බ්වින්ඩි ඉන්පෙනෙට්රබල් ජාතික වනෝද්යානය සහ ර්වෙන්සෝරි කඳු ජාතික වනෝද්යානය (UNESCO ලෝක උරුම අඩවි දෙකම[69]), කිබාලේ ජාතික වනෝද්යානය, කිඩෙපෝ නිම්නය ජාතික වනෝද්යානය, ලේක් ම්බුරෝ ජාතික වනෝද්යානය, ම්ගහිංගා ගෝරිල්ලා ජාතික උද්යානය, මවුන්ට් එල්ගොන් ජාතික වනෝද්යානය, මර්චිසන් දිය ඇල්ල ජාතික වනෝද්යානය, එලිසබෙත් රැජින ජාතික වනෝද්යානය සහ සෙමුලිකි ජාතික උද්යානය.

බ්වින්ඩි ඉන්පෙනෙට්රබල් ජාතික වනෝද්යානයේ කඳුකර ගෝරිල්ලන්, ම්ගහිංගා ගෝරිල්ලා ජාතික වනෝද්යානයේ ගෝරිල්ලන් සහ රන් වඳුරන් සහ මර්චිසන් ඇල්ල ජාතික වනෝද්යානයේ හිපෝ ඇතුළු විශේෂ විශාල සංඛ්යාවක් උගන්ඩාවේ වාසය කරයි.[70] කොස් රට පුරා ද සොයා ගත හැක.[71]

රටෙහි 2019 වනාන්තර භූ දර්ශන අඛණ්ඩතා දර්ශකයේ මධ්යන්ය ලකුණු 4.36/10ක් තිබූ අතර, එය රටවල් 172ක් අතරින් ගෝලීය වශයෙන් 128 වැනි ස්ථානයට පත් විය.[72]

රජය සහ දේශපාලනය[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාවේ ජනාධිපතිවරයා රාජ්ය නායකයා මෙන්ම රජයේ ප්රධානියා ද වේ. ජනාධිපතිවරයා ඔහුට පාලනය කිරීමට සහාය වීම සඳහා උප ජනාධිපතිවරයෙකු සහ අගමැතිවරයෙකු පත් කරයි.

පාර්ලිමේන්තුව පිහිටුවා ඇත්තේ මන්ත්රීවරුන් 449 දෙනෙකුගෙන් සමන්විත ජාතික සභාව මගිනි. මැතිවරණ කොට්ඨාශ නියෝජිතයින් 290 ක්, දිස්ත්රික් කාන්තා නියෝජිතයින් 116 ක්, උගන්ඩා මහජන ආරක්ෂක බලකායේ නියෝජිතයින් 10 ක්, තරුණ නියෝජිතයින් 5 ක්, කම්කරු නියෝජිතයින් 5 ක්, ආබාධ සහිත පුද්ගලයින්ගේ නියෝජිතයින් 5 ක් සහ නිල බලයෙන් යුත් සාමාජිකයින් 18 දෙනෙකු මෙයට ඇතුළත් වේ.[73]

විදේශ සබඳතා[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාව කෙන්යාව, ටැන්සානියාව, රුවන්ඩාව, බුරුන්ඩි සහ දකුණු සුඩානය සමඟින් නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු ප්රජාවේ (ඊඒසී) සාමාජිකයෙකි. 2010 නැගෙනහිර අප්රිකානු පොදු වෙළෙඳපොළ ප්රොටෝකෝලයට අනුව, රැකියා අරමුණු සඳහා වෙනත් සාමාජික රටක පදිංචි වීමේ අයිතිය ඇතුළුව මිනිසුන්ගේ නිදහස් වෙළඳාම සහ නිදහස් සංචලනය සහතික කෙරේ. කෙසේ වෙතත්, මෙම ප්රොටෝකෝලය, වැඩ බලපත්රය සහ අනෙකුත් නිලධර, නීතිමය සහ මූල්ය බාධාවන් නිසා ක්රියාත්මක කර නොමැත. උගන්ඩාව යනු සංවර්ධනය පිළිබඳ අන්තර් රාජ්ය අධිකාරියේ (IGAD) ආරම්භක සාමාජිකයෙකි, එය අප්රිකාවේ අං, නයිල් නිම්නය සහ අප්රිකානු මහා විල් ඇතුළු රටවල් අටකින් සමන්විත කණ්ඩායමකි.[74] එහි මූලස්ථානය ජිබුටි නගරයේ පිහිටා ඇත. උගන්ඩාව ඉස්ලාමීය සහයෝගිතා සංවිධානයේ ද සාමාජිකයෙකි.[75]

හමුදා බලය[සංස්කරණය]

උගන්ඩාවේ, උගන්ඩා මහජන ආරක්ෂක බලකාය හමුදාව ලෙස සේවය කරයි. උගන්ඩාවේ හමුදා සාමාජිකයින් සංඛ්යාව ක්රියාකාරී රාජකාරියේ යෙදී සිටින සොල්දාදුවන් 45,000 ක් ලෙස ගණන් බලා ඇත. උගන්ඩා හමුදාව කලාපයේ සාම සාධක සහ සටන් මෙහෙයුම් කිහිපයකට සම්බන්ධ වන අතර, විචාරකයින් සඳහන් කරන්නේ එක්සත් ජනපද සන්නද්ධ හමුදාවන් පමණක් වැඩි රටවල යොදවා ඇති බවයි. උගන්ඩාව කොංගෝ ප්රජාතන්ත්රවාදී ජනරජයේ උතුරු සහ නැගෙනහිර ප්රදේශවල සහ මධ්යම අප්රිකානු ජනරජය, සෝමාලියාව සහ දකුණු සුඩානය යන ප්රදේශවල සොල්දාදුවන් යොදවා ඇත.[76]

දූෂණය[සංස්කරණය]

ට්රාන්ස්පේරන්සි ඉන්ටර්නැෂනල් ආයතනය උගන්ඩාවේ රාජ්ය අංශය ලොව දූෂිතම එකක් ලෙස ශ්රේණිගත කර ඇත. 2016 දී, උගන්ඩාව 176 න් 151 වැනි හොඳම ස්ථානයට පත් වූ අතර 0 (වඩාත්ම දූෂිත ලෙස සැලකේ) සිට 100 (පිරිසිදු යැයි සැලකේ) දක්වා පරිමාණයෙන් ලකුණු 25 ක් ලබා ගෙන ඇත.[77]

ලෝක බැංකුවේ 2015 ලෝක ව්යාප්ත පාලන දර්ශක උගන්ඩාව සියලුම රටවල් අතරින් නරකම සියයට 12 ලෙස ශ්රේණිගත කර ඇත.[78] එක්සත් ජනපද රාජ්ය දෙපාර්තමේන්තුවේ 2012 මානව හිමිකම් වාර්තාවට අනුව උගන්ඩාව පිළිබඳ, "ලෝක බැංකුවේ නවතම ලෝක ව්යාප්ත පාලන දර්ශක මගින් දූෂණය බරපතල ගැටලුවක් විය" සහ "රටට වාර්ෂිකව දූෂණය හේතුවෙන් සිලිං බිලියන 768.9 (ඩොලර් මිලියන 286) අහිමි වේ."[79]

2014 දී උගන්ඩාවේ පාර්ලිමේන්තු මන්ත්රීවරු බොහෝ රාජ්ය සේවකයින් උපයාගත් ආදායම මෙන් 60 ගුණයක් උපයා ගත් අතර ඔවුන් විශාල වැඩිවීමක් අපේක්ෂා කළහ. මෙය 2014 ජූනි මාසයේදී පාර්ලිමේන්තු මන්ත්රීවරුන් අතර දූෂිතයන් හුවා දැක්වීමට ඌරු පැටවුන් දෙදෙනෙකු පාර්ලිමේන්තුවට ගෙන ඒම ඇතුළු පුලුල් විවේචන සහ විරෝධතාවලට හේතු විය. අත්අඩංගුවට ගත් විරෝධතාකරුවන්, ඔවුන්ගේ දුක්ගැනවිලි ඉස්මතු කිරීමට "MPigs" යන වචනය භාවිතා කළහ.[80]

සැලකිය යුතු ජාත්යන්තර ප්රතිවිපාක ඇති කළ සහ ඉහළ මට්ටමේ රජයේ කාර්යාලවල දූෂණ පවතින බව ඉස්මතු කළ විශේෂිත සෝලියක් වූයේ 2012 දී අගමැති කාර්යාලයෙන් ඩොලර් මිලියන 12.6 ක පරිත්යාගශීලී අරමුදල් වංචා කිරීම ය. වසර 20ක යුද්ධයකින් විනාශ වූ උතුරු උගන්ඩාව සහ උගන්ඩාවේ දුප්පත්ම කලාපය වන කරමෝජා යළි ගොඩනැගීම." මෙම සෝලිය EU, එක්සත් රාජධානිය, ජර්මනිය, ඩෙන්මාර්කය, අයර්ලන්තය සහ නෝර්වේ ආධාර අත්හිටුවීමට පොළඹවන ලදී.[81]

රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන් සහ දේශපාලන අනුග්රහ පද්ධති සම්බන්ධ පුලුල්ව පැතිරුනු මහා සහ සුළු දූෂණ ද උගන්ඩාවේ ආයෝජන වාතාවරණයට බරපතල ලෙස බලපා ඇත. ඉහළ දූෂණ අවදානම් ක්ෂේත්රවලින් එකක් වන්නේ මහජන ප්රසම්පාදනය වන අතර එහිදී ප්රසම්පාදන නිලධාරීන්ගෙන් විනිවිද පෙනෙන නොවන මුදල් ගෙවීම් බොහෝ විට ඉල්ලා සිටී.[82]

මෙම ගැටලුව අවසානයේ සංකීර්ණ විය හැක්කේ තෙල් ලබා ගැනීමේ හැකියාවයි. 2012 දී පාර්ලිමේන්තුව විසින් සම්මත කරන ලද සහ NRM විසින් තෙල් අංශයට විනිවිදභාවයක් ගෙන එන ලෙස හුවා දක්වන ලද ඛනිජ තෙල් පනත දේශීය හා ජාත්යන්තර දේශපාලන විචාරකයින් සහ ආර්ථික විද්යාඥයින් සතුටු කිරීමට අපොහොසත් වී ඇත. නිදසුනක් වශයෙන්, එක්සත් ජනපදය පදනම් කරගත් විවෘත සමාජ පදනමේ උගන්ඩාවේ බලශක්ති විශ්ලේෂකයෙකු වන ඇන්ජලෝ ඉසාමා පැවසුවේ නව නීතිය මුසවේනිට සහ ඔහුගේ පාලන තන්ත්රයට "ATM (මුදල්) යන්ත්රයක් භාර දීමට" සමාන බවයි.[83] 2012 දී Global Witness ට අනුව, ජාත්යන්තර නීතියට කැප වූ රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධානයක්, උගන්ඩාවේ දැන් "වසර හයේ සිට දහය දක්වා කාලය තුළ රජයේ ආදායම දෙගුණ කිරීමට හැකියාව ඇති තෙල් සංචිත ඇති අතර, ඇස්තමේන්තුගත වසරකට ඇමරිකානු ඩොලර් බිලියන 2.4 ක වටිනාකමක් ඇත."[84]

2006 දී සම්මත කරන ලද රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන (සංශෝධන) පනත, ක්ෂේත්රය තුළට ඇතුළුවීම, ක්රියාකාරකම්, අරමුදල් සහ එකලස් කිරීම සඳහා බාධා කිරීම් හරහා රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධානවල ඵලදායිතාව අඩාල කර ඇත. බර සහ දූෂිත ලියාපදිංචි කිරීමේ ක්රියා පටිපාටි (එනම් රාජ්ය නිලධාරීන්ගේ නිර්දේශ අවශ්ය වීම; වාර්ෂික නැවත ලියාපදිංචි කිරීම), අසාධාරණ මෙහෙයුම් නියාමනය (එනම් රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධානයේ උනන්දුවක් දක්වන ක්ෂේත්රයේ පුද්ගලයින් සමඟ සම්බන්ධ වීමට පෙර රජයේ දැනුම්දීමක් අවශ්ය කිරීම) සහ සියලුම විදේශීය අරමුදල් සම්මත කර ගැනීමේ පූර්ව කොන්දේසිය උගන්ඩා බැංකුව හරහා, වෙනත් දේ අතර, රාජ්ය නොවන සංවිධාන අංශයේ නිෂ්පාදනය දැඩි ලෙස සීමා කරයි. තවද, බිය ගැන්වීම් හරහා එම අංශයේ භාෂණයේ නිදහස අඛණ්ඩව උල්ලංඝනය වී ඇති අතර, මෑත කාලීන මහජන සාමය කළමනාකරණ පනත් කෙටුම්පත (එක්රැස්වීමේ නිදහස දැඩි ලෙස සීමා කිරීම) රජයේ පතොරම් තොගයට එකතු කරනු ඇත.[85]

මානව හිමිකම්[සංස්කරණය]

There are many areas which continue to attract concern when it comes to human rights in Uganda.

Conflict in the northern parts of the country continues to generate reports of abuses by both the rebel Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), led by Joseph Kony, and the Ugandan Army. A UN official accused the LRA in February 2009 of "appalling brutality" in the Democratic Republic of Congo.[86]

The number of internally displaced persons is estimated at 1.4 million. Torture continues to be a widespread practice amongst security organisations. Attacks on political freedom in the country, including the arrest and beating of opposition members of parliament, have led to international criticism, culminating in May 2005 in a decision by the British government to withhold part of its aid to the country. The arrest of the main opposition leader Kizza Besigye and the siege of the High Court during a hearing of Besigye's case by heavily armed security forces – before the February 2006 elections – led to condemnation.[87]

Child labour is common in Uganda. Many child workers are active in agriculture.[88] Children who work on tobacco farms in Uganda are exposed to health hazards.[88] Child domestic servants in Uganda risk sexual abuse.[88] Trafficking of children occurs.[88] Slavery and forced labour are prohibited by the Ugandan constitution.[88]

The US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants reported several violations of refugee rights in 2007, including forcible deportations by the Ugandan government and violence directed against refugees.[89]

Torture and extrajudicial killings have been a pervasive problem in Uganda in recent years. For instance, according to a 2012 US State Department report, "the African Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation for Torture Victims registered 170 allegations of torture against police, 214 against the UPDF, 1 against military police, 23 against the Special Investigations Unit, 361 against unspecified security personnel, and 24 against prison officials" between January and September 2012.[79]

In September 2009, Museveni refused Kabaka Muwenda Mutebi, the Baganda king, permission to visit some areas of Buganda Kingdom, particularly the Kayunga district. Riots occurred and over 40 people were killed while others still remain imprisoned. Furthermore, 9 more people were killed during the April 2011 "Walk to Work" demonstrations. According to the Humans Rights Watch 2013 World Report on Uganda, the government has failed to investigate the killings associated with both of these events.[90]

LGBT හිමිකම්[සංස්කරණය]

In 2007 a newspaper, the Red Pepper, published a list of allegedly gay men, many of whom suffered harassment as a result.[91]

On 9 October 2010, the Ugandan newspaper Rolling Stone published a front-page article titled "100 Pictures of Uganda's Top Homos Leak" that listed the names, addresses, and photographs of 100 homosexuals alongside a yellow banner that read "Hang Them."[92] The paper also alleged Homosexual recruitment of Ugandan children. The publication attracted international attention and criticism from human rights organisations, such as Amnesty International,[93] No Peace Without Justice[94] and the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association.[95] According to gay rights activists, many Ugandans have been attacked since the publication.[96] On 27 January 2011, gay rights activist David Kato was murdered.[97]

In 2009, the Ugandan parliament considered an Anti-Homosexuality Bill which would have broadened the criminalisation of homosexuality by introducing the death penalty for people who have previous convictions, or are HIV-positive, and engage in same-sex sexual acts. The bill included provisions for Ugandans who engage in same-sex sexual relations outside of Uganda, asserting that they may be extradited back to Uganda for punishment, and included penalties for individuals, companies, media organisations, or non-governmental organizations that support legal protection for homosexuality or sodomy. On 14 October 2009, MP David Bahati submitted the private member's bill and was believed to have had widespread support in the Uganda parliament.[98] The hacktivist group Anonymous hacked into Ugandan government websites in protest of the bill.[99] In response to global condemnation the debate of the bill was delayed, but it was eventually passed on 20 December 2013 and President Museveni signed it on 24 February 2014. The death penalty was dropped in the final legislation. The law was widely condemned by the international community. Denmark, the Netherlands, and Sweden said they would withhold aid. On 28 February 2014 the World Bank said it would postpone a US$90 million loan, while the United States said it was reviewing ties with Uganda.[100] On 1 August 2014, the Constitutional Court of Uganda ruled the bill invalid as it was not passed with the required quorum.[101][102][103] A 13 August 2014 news report said that the Ugandan attorney general had dropped all plans to appeal, per a directive from President Museveni who was concerned about foreign reaction to the bill and who also said that any newly introduced bill should not criminalise same-sex relationships between consenting adults.[104] As of 2019 progress on the African continent was slow but progressing with South Africa being the only country where same sex marriages are recognised.[105]

2023 සමලිංගික විරෝධී පනත[සංස්කරණය]

On 21 March 2023, the Ugandan parliament passed a bill that would make identifying as homosexual punishable by life in prison and the death penalty for anyone found guilty of "aggravated homosexuality."[106][107]

On 9 March 2023 Asuman Basalirwa, a member of parliament since 2018 from the opposition representing Bugiri Municipality on Justice Forum party ticket tabled a proposed law which seeks out to castigate gay sex and "the promotion or recognition of such relations" and he made remarks that: "In this country, or in this world, we talk about human rights. But it is also true that there are human wrongs. I want to submit that homosexuality is a human wrong that offends the laws of Uganda and threatens the sanctity of the family, the safety of our children and the continuation of humanity through reproduction."[108] The speaker of parliament, Annet Anita Among, referred the bill to a house committee for scrutiny, the first step in an accelerated process to pass the proposal into law. The parliament speaker had earlier noted that: "We want to appreciate our promoters of homosexuality for the social economic development they have brought to the country," in reference to western countries and donors. "But we do not appreciate the fact that they are killing morals. We do not need their money, we need our culture." during a prayer service held in parliament and attended by several religious leaders.[109] The Speaker vowed to pass the bill into law at whatever cost to shield Uganda's culture and its sovereignty.[110]

On March 21, 2023, parliament rapidly passed the anti-homosexuality bill with overwhelming support.[111]

The United States strongly condemned the bill. During a White House Press briefing on March 22, 2023, Karine Jean-Pierre stated. "Human rights are universal. No one should be attacked, imprisoned, or killed simply because of who they are or whom they love."[112] In the following days, further criticism came from the United Kingdom,[113] Canada,[114] Germany,[115] and the European Union.

පරිපාලන අංශ[සංස්කරණය]

2022 වන විට[update], Uganda is divided into four Regions of Uganda and 136 districts.[116][117] Rural areas of districts are subdivided into sub-counties, parishes, and villages. Municipal and town councils are designated in urban areas of districts.[118]

Political subdivisions in Uganda are officially served and united by the Uganda Local Governments Association (ULGA), a voluntary and non-profit body which also serves as a forum for support and guidance for Ugandan sub-national governments.[119]

Parallel with the state administration, five traditional Bantu kingdoms have remained, enjoying some degrees of mainly cultural autonomy. The kingdoms are Toro, Busoga, Bunyoro, Buganda, and Rwenzururu. Furthermore, some groups attempt to restore Ankole as one of the officially recognised traditional kingdoms, to no avail yet.[120] Several other kingdoms and chiefdoms are officially recognised by the government, including the union of Alur chiefdoms, the Iteso paramount chieftaincy, the paramount chieftaincy of Lango and the Padhola state.[121]

ආර්ථිකය සහ යටිතල පහසුකම්[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[122]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[123]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[124]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[126] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[127] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[128] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[130]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[132] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[133][134]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[135] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[136] and seventh in Africa.[137] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[138] South Sudan,[139] and Rwanda.[140]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[141] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[142]

කර්මාන්ත[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[143]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[144]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[145]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[146] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[147] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[148] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[149]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[150] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[151][152]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[153] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[154] and seventh in Africa.[155] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[156] South Sudan,[157] and Rwanda.[158]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[159] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[160]

දරිද්රතාව[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[161]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[162]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[163]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[164] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[165] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[166] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[167]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[168] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[169][170]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[171] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[172] and seventh in Africa.[173] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[174] South Sudan,[175] and Rwanda.[176]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[177] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[178]

ගුවන් ප්රවාහනය[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[179]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[180]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[181]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[182] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[183] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[184] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[185]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[186] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[187][188]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[189] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[190] and seventh in Africa.[191] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[192] South Sudan,[193] and Rwanda.[194]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[195] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[196]

මාර්ග ජාලය[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[197]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[198]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[199]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[200] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[201] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[202] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[203]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[204] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[205][206]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[207] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[208] and seventh in Africa.[209] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[210] South Sudan,[211] and Rwanda.[212]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[213] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[214]

දුම්රිය මාර්ග[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[215]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[216]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[217]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[218] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[219] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[220] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[221]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[222] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[223][224]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[225] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[226] and seventh in Africa.[227] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[228] South Sudan,[229] and Rwanda.[230]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[231] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[232]

සන්නිවේදනය[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[233]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[234]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[235]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[236] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[237] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[238] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[239]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[240] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[241][242]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[243] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[244] and seventh in Africa.[245] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[246] South Sudan,[247] and Rwanda.[248]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[249] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[250]

බලශක්තිය[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[251]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[252]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[253]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[254] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[255] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[256] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[257]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[258] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[259][260]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[261] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[262] and seventh in Africa.[263] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[264] South Sudan,[265] and Rwanda.[266]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[267] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[268]

ජල සැපයුම සහ සනීපාරක්ෂාව[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[269]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[270]

The country has been experiencing consistent economic growth. In fiscal year 2015–16, Uganda recorded gross domestic product growth of 4.6 percent in real terms and 11.6 percent in nominal terms. This compares to 5.0 percent real growth in fiscal year 2014–15.[271]:vii

The country has largely untapped reserves of both crude oil and natural gas.[125] While agriculture accounted for 56 percent of the economy in 1986, with coffee as its main export, it has now been surpassed by the services sector, which accounted for 52 percent of GDP in 2007.[272] In the 1950s, the British colonial regime encouraged some 500,000 subsistence farmers to join co-operatives.[273] Since 1986, the government (with the support of foreign countries and international agencies) has acted to rehabilitate an economy devastated during the regime of Idi Amin[274] and the subsequent civil war.[129]

In 2012, the World Bank still listed Uganda on the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries list.[275]

Economic growth has not always led to poverty reduction. Despite an average annual growth of 2.5 percent between 2000 and 2003, poverty levels increased by 3.8 percent during that time.[131] This has highlighted the importance of avoiding jobless growth and is part of the rising awareness in development circles of the need for equitable growth not just in Uganda, but across the developing world.[131]

With the Uganda securities exchanges established in 1996, several equities have been listed. The government has used the stock market as an avenue for privatisation. All government treasury issues are listed on the securities exchange. The Capital Markets Authority has licensed 18 brokers, asset managers, and investment advisors including: African Alliance Investment Bank, Baroda Capital Markets Uganda Limited, Crane Financial Services Uganda Limited, Crested Stocks and Securities Limited, Dyer & Blair Investment Bank, Equity Stock Brokers Uganda Limited, Renaissance Capital Investment Bank and UAP Financial Services Limited.[276] As one of the ways of increasing formal domestic savings, pension sector reform is the centre of attention (2007).[277][278]

Uganda traditionally depends on Kenya for access to the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa. Efforts have intensified to establish a second access route to the sea via the lakeside ports of Bukasa in Uganda and Musoma in Tanzania, connected by railway to Arusha in the Tanzanian interior and to the port of Tanga on the Indian Ocean.[279] Uganda is a member of the East African Community and a potential member of the planned East African Federation.

Uganda has a large diaspora, residing mainly in the United States and the United Kingdom. This diaspora has contributed enormously to Uganda's economic growth through remittances and other investments (especially property). According to the World Bank, Uganda received in 2016 an estimated US$1.099 billion in remittances from abroad, second only to Kenya (US$1.574 billion) in the East African Community,[280] and seventh in Africa.[281] Uganda also serves as an economic hub for a number of neighbouring countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo,[282] South Sudan,[283] and Rwanda.[284]

The Ugandan Bureau of Statistics announced inflation was 4.6 percent in November 2016.[285] On 29 June 2018, Uganda's statistics agency said the country registered a drop in inflation to 3.4 percent in the financial year ending 2017/18 compared to the 5.7 percent recorded in the financial year 2016/17.[286]

අධ්යාපනය[සංස්කරණය]

The Bank of Uganda is the central bank of Uganda and handles monetary policy along with the printing of the Ugandan shilling.[287]

In 2015, Uganda's economy generated export income from the following merchandise: coffee (US$402.63 million), oil re-exports (US$131.25 million), base metals and products (US$120.00 million), fish (US$117.56 million), maize (US$90.97 million), cement (US$80.13 million), tobacco (US$73.13 million), tea (US$69.94 million), sugar (US$66.43 million), hides and skins (US$62.71 million), cocoa beans (US$55.67 million), beans (US$53.88 million), simsim (US$52.20 million), flowers (US$51.44 million), and other products (US$766.77 million).[288]