නවයොවුන් ලිංගිකත්වය

මෙම ලිපිය පරිවර්තනය කළ යුතුය කරුණාකර මෙම ලිපිය සිංහල භාෂාවට පරිවර්තනය කිරීමෙන් දායකවන්න. |

නවයොවුන් ලිංගිකත්වය යනු නවයෞවනයන්ගේ ලිංගික හැගීම්, හැසිරීම් සහ මනෝලිංගික සංවර්ධනය ඇතුළත් කරගත් මානව ලිංගිකත්වයේ නිශ්චිත අවධියක් වේ. ලිංගිකත්වය නවයොවුන් දිවිය තුළ නිරන්තර ව සක්රීය භූමිකාවකට හිමිකම් කියන්නකි. ඔවුන්ගේ සංස්කෘතික වටිනාකම් සහ සමාජ සම්මතයන්, ඔවුන්ගේ ලිංගික දිශානතිය, සහ ලිංගික ව හැසිරිය හැකි අවම නෛතික වයස් සීමාව වැනි සමාජීය සීමාකිරීම් බොහෝ අවස්ථාවන්වල දී නවයොවුන් ලිංගිකත්වය කෙරෙහි බලපෑම් කරන සාධක ලෙස දැක්විය හැකි ය.

මානව විශේෂය තුළ සාමාන්යයෙන් පරිණත ලිංගික ආශාවක් ඇතිවනු දැකිය හැකිවන්නේ යෞවනෝදය උදාවීමත් සමග ය. ලිංගිකමය භාවයන් ස්වයං වින්දනය හෝ සහකරුවතු සමග ලිංගික හැසිරිම වැනි ස්වරූපයක් තුළ ප්රකාශ විය හැකි ය. වැඩිහිටියන්ගේ මෙන් ම නවයෞවනයන්ගේ ලිංගික රුචිකත්වයන් ද සෑහෙන විවිධත්වයකට හිමිකම් කියති. නවයොවුන් ලිංගික හැසිරීම් බොහෝවිට අනවශ්ය ගැබ්ගැනීම් සහ එච්. අයි.වී. ඇතුළු ලිංගික ව සම්ප්රේෂණය වන රෝග සමග බැඳී පවතී.

නවයොවුන් ලිංගිකත්වය හා සබැඳි අවදානම් තත්ත්වයන් උත්සන්න වීමට ඔවුන්ගේ මොළය නියුරෝනමය ලෙස පූර්ණසංවර්ධිත නොවීම ද හේතු විය හැකි ය. ස්වයං පාලනයට, ආශාවන් මැඩගැනීමට සහ අවදානම් හැඳිනීමට වැදගත් වන ලලාට ඛණ්ඩිකාවේ මස්තිෂ්ක වල්කයෙහි සහ හයිපොතැලමසයෙහි ප්රදේශ කීපයක් මෙම අවධිය වන විට ද මුළුමනින් ම විකසනය වී නැත. වයස අවුරුදු 25ක් වන තුරු ම මිනිස් මොළය පූර්ණ ලෙස සංවර්ධනය නොවේ.මෙයට හේතුව වශයෙන් තරුණ අසරණ දරුවන්ට හොඳ තීරණ ගැනීමට සහ ලිංගික හැසිරීම් වල ප්රතිවිපාක අපේක්ෂා කිරීම සඳහා වැඩිහිටියන් සාමාන්යයෙන් අඩු මට්ටමක පවතී. යෞවනයන් තුළ මොළයේ හැසිරීම් සහ චර්යාවන්ට සම්බන්ධිත සම්බන්ධතා අධ්යයනයන් විවේචනයට ලක් නොකළ අතර ඒවාට හේතුවක් නොවන බව හා ඇතැම් විට සංස්කෘතික අන්තරායන් යළි තහවුරු කර ගැනීම සඳහා විවේචනයට ලක් කර ඇත.

Development of sexuality[සංස්කරණය]

නවයොවුන් ලිංගිකත්වය ඇරඹෙන්නේ යෞවනෝදයෙනි. ලිංගික ව පරිණත වීමේ ක්රියාවලිය ලිංගික රුචියක් සහ චින්තාවලියක් ගොඩනංවයි. හයිපොතැලමසය සහ පූර්ව පිටියුටරි ග්රන්ථිය විසින් හෝර්මෝන ස්රාවය කිරීමත් සමග ලිංගික හැසිරීම් සඳහා අවශ්ය ජීවවිද්යාත්මක වෙනස්කම් සිදු වේ. මෙම හෝර්මෝන ලිංගික ඉන්ද්රියන් ඉළක්ක කරගනිමින් ඒවා පරිණත බවට පත්කිරීම සිදු කරයි.. Increasing levels of androgen and estrogen have an effect on the thought processes of adolescents and can be described as them being in the minds "of almost all adolescents a good deal of the time".[1]

බොහෝ නවයෞවනියන්ගේ ලිංගික ව පරිණත විමේ ක්රියාවලිය සාමාන්ය සහ අපේක්ෂිත අන්දමින් සිදු වුවද පහත සඳහන් තත්ත්වයන් පිළිබඳ ව මවුපියන් සහ විශේෂඥයන් විශේෂයෙන් සැලකිලිමත් වේ.

- ආර්තවයේ දී වේදනාකාරී තත්ත්වයක් ඇතිවිම

- ශ්රෝණි ප්රදේශයේ දැඩි වේදනාවක් ඇති වීම

- ඔසප් රුධිරය මුළුමනින් ම බැහැර කළ නොහැකි වීම/අජිද්ර හයිමනයක් තිබිම

- වෙනත් ශරීරාභ්යයන්තර අපරූපීතාවන්[2]

Behavior[සංස්කරණය]

| Country | Boys (%) | Girls (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 21.7 | 17.9 |

| Canada | 24.1 | 23.9 |

| Croatia | 21.9 | 8.3 |

| England | 34.9 | 39.9 |

| Estonia | 18.8 | 14.1 |

| Finland | 23.1 | 32.7 |

| Belgium | 24.6 | 23 |

| France | 25.1 | 17.7 |

| Greece | 32.5 | 9.5 |

| Hungary | 25 | 16.3 |

| Israel | 31 | 8.2 |

| Latvia | 19.2 | 12.4 |

| Lithuania | 24.4 | 9.2 |

| Macedonia | 34.2 | 2.7 |

| Netherlands | 23.3 | 20.5 |

| Poland | 20.5 | 9.3 |

| Portugal | 29.2 | 19.1 |

| Scotland | 32.1 | 34.1 |

| Slovenia | 45.2 | 23.1 |

| Spain | 17.2 | 13.9 |

| Sweden | 24.6 | 29.9 |

| Switzerland | 24.1 | 20.3 |

| Ukraine | 47.1 | 24 |

| Wales | 27.3 | 38.5 |

Views on sexual activity[සංස්කරණය]

One study from 1996 documented the interviews of a sample of adolescent girls and boys. The girls were less likely to state that they ever had sex than adolescent boys. Among boys and girls who had experienced sexual intercourse, the proportion of girls and boys who had recently had sex and were regularly sexually active was the same.[3] Those conducting the study speculated that fewer girls say they have ever had sex because girls viewed teenage parenthood as more of a problem than boys. Girls were thought to be more restricted in their sexual attitudes; they were more likely than boys to believe that they would be able to control their sexual urges. Girls had a more negative association in how being sexually active could affect their future goals. In general, girls said they felt less pressure from peers to begin having sex, while boys reported feeling more pressure.[3]

A later study questioned the attitudes of adolescents. When asked about abstinence, many girls reported they felt conflicted. They were trying to balance maintaining a good reputation with trying to maintain a romantic relationship and wanting to behave in adult-like ways. Boys viewed having sex as social capital. Many boys believed that their male peers who were abstinent would not as easily climb the social ladder as sexually active boys. Some boys said that for them, the risks that may come from having sex were not as bad as the social risks that could come from remaining abstinent.[4]

Birth control[සංස්කරණය]

In 2002, a survey was conducted in European nations about the sexual behavior of teenagers. In a sample of fifteen year olds from 24 countries, it found that most self-reported that they had not experienced sexual intercourse. Among those who were sexually active, the majority (82%) used contraception.[5]

Teenage girls who use the most common form of birth control pills, combination birth control pills with both estrogen and progestin, are 80% more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant than girls who were not taking them.[6] Girls who take progestin-only pills are 120% more likely.[6] The risk of depression is tripled for teenage girls who use non-oral forms of hormonal contraception.[6]

Concepts about loss of virginity[සංස්කරණය]

In the United States, federally mandated programs begun in 1980, promoted adolescent abstinence from sexual intercourse, resulting in teens turning to oral sex, which about a third of teens in a study considered a form of abstinence.[7]

After their first act of sexual intercourse, adolescent girls generally see themselves in one of the following ways: as a gift, a stigma, or a normal step in development. Girls typically think of virginity as a gift, while boys think of virginity as a stigma.[8] In interviews, girls said that they viewed giving someone their virginity like giving them a very special gift. Because of this, they often expected something in return such as increased emotional intimacy with their partners or the virginity of their partner. However, they often felt disempowered because of this; they often did not feel like they actually received what they expected in return and this made them feel like they had less power in their relationship. They felt that they had given something up and didn’t feel like this action was recognized.[8]

Thinking of virginity as a stigma disempowered many boys because they felt deeply ashamed and often tried to hide the fact that they were virgins from their partners, which for some resulted in their partners teasing them and criticizing them about their limited sexual techniques. The girls who viewed virginity as a stigma did not experience this shaming. Even though they privately thought of virginity as a stigma, these girls believed that society valued their virginity because of the stereotype that women are sexually passive. This, they said, made it easier for them to lose their virginities once they wanted to because they felt society had a more positive view on female virgins and that this may have made them sexually attractive. Thinking of losing virginity as part of a natural developmental process resulted in less power imbalance between boys and girls because these individuals felt less affected by other people and were more in control of their individual sexual experience.[8] Adolescent boys, however, were more likely than adolescent girls to view their loss of virginity as a positive aspect of their sexuality because it is more accepted by peers.[8]

Adolescent sexual functioning: gender similarities and differences[සංස්කරණය]

Lucia O’Sullivan and her colleagues studied adolescent sexual functioning; they compared an adolescent sample with an adult sample and found no significant differences between them. Desire, satisfaction and sexual functioning were generally high among their sample of participants (aged 17–21). Additionally, no significant gender differences were found in the prevalence of sexual dysfunction.[9] In terms of problems with sexual functioning mentioned by participants in this study, the most common problems listed for males were experiencing anxiety about performing sexually (81.4%) and premature ejaculation (74.4%). Other common problems included issues becoming erect and difficulties with ejaculation. Generally, most problems were not experienced on a chronic basis. Common problems for girls included difficulties with sexual climax (orgasm) (86.7%), not feeling sexually interested during a sexual situation (81.2%), unsatisfactory vaginal lubrication (75.8%) anxiety about performing sexually (75.8%) and painful intercourse (25.8%). Most problems listed by the girls were not persistent problems. However, inability to experience orgasm seemed to be an issue that was persistent for some participants.[9]

The authors detected four trends during their interviews: sexual pleasure increased with the amount of sexual experience the participants had; those who had experienced sexual difficulties were typically sex-avoidant; some participants continued to engage in regular sexual activity even if they had low interest; and lastly, many experienced pain when engaging in sexual activity if they experienced low arousal.[9]

Another study found that it was not uncommon for adolescent girls in relationships to report they felt little desire to engage in sexual activity when they were in relationships. However, many girls engaged in sexual activity even if they did not desire it, in order to avoid what they think might place strains on their relationships.[10] The researcher states that this may be because of society's pressure on girls to be "good girls"; the pressure to be "good" may make adolescent girls think they are not supposed to feel desire like boys do. Even when girls said they did feel sexual desire, they said that they felt like they were not supposed to, and often tried to cover up their feelings. This is an example of how societal expectations about gender can impact adolescent sexual functioning.[10]

Same-sex attractions among adolescents[සංස්කරණය]

Adolescent girls and boys who are attracted to others of the same sex are strongly affected by their surroundings in that adolescents often decide to express their sexualities or keep them secret depending on certain factors in their societies. These factors affect girls and boys differently. If girls’ schools and religions are against same sex attractions, they pose the greatest obstacles to girls who experience same sex attractions. These factors were not listed as affecting boys as much. The researchers suggest that maybe this is because not only are some religions against same-sex attraction, but they also encourage traditional roles for women and do not believe that women can carry out these roles as lesbians. Schools may affect girls more than boys because strong emphasis is placed on girls to date boys, and many school activities place high importance on heterosexuality (such as cheerleading).[11] Additionally, the idea of not conforming to typical male gender roles inhibited many boys from openly expressing their same-sex attraction. The worry of conforming to gender roles didn’t inhibit girls from expressing their same-gender preferences as much, because society is generally more flexible about their gender expression.[11]

Researchers such as Lisa Diamond are interested in how some adolescents depart from the socially constructed norms of gender and sexuality. She found that some girls, when faced with the option of choosing "heterosexual", "same-sex attracted" or "bisexual", preferred not to choose a label because their feelings do not fit into any of those categories.[12]

In Brazil[සංස්කරණය]

The average age Brazilians lose their virginity is 17.4 years of age, the second lowest number in the countries researched (first was Austria), according to the 2007 research finding these results, and they also ranked low at using condoms at their first time, at 47.9% (to the surprise of the researchers, people of lower socioeconomic status were far more likely to do so than those of higher ones). 58.4% of women reported that it was in a committed relationship, versus solely 18.9% of men (traditional Mediterranean cultures-descended mores tend to enforce strongly about male sexual prowess equating virility and female quality being chastity and purity upon marriage), and scored among the countries where people have the most positive feelings about their first time, feeling pleasure and more mature afterwards (versus the most negative attitudes coming from Japan).[13]

In another research, leading the international ranking, 29.6% of Brazilian men lost their virginity before age 15 (versus 8.8% of women), but the average is really losing virginity at age 16.5 and marrying at age 24 for men, and losing virginity at age 18.5 and marrying at age 20 for women.[14] These do not differ much from national figures. In 2005, 80% of then adolescents lost their virginity before their seventeenth birthday, and about 1 in each 5 new children in the country were born to an adolescent mother,[15] where the number of children per women is solely 1.7 in average, below the natural replacement and the third lowest in independent countries of the Americas, after Canada and Cuba.

A 2013 report through national statistics of students of the last grade before high school, aged generally (86%) 13–15, found out 28.7% of them already had lost their virginity, with both demographics of 40.1% of boys and 18.3% of girls having reduced their rate since the last research, in 2009, that found the results as 30.5% overall, 43.7% for boys and 18.7% for girls. Further about the 2013 research, 30.9% of those studying in public schools were already sexually initiated, versus 18% in private ones; 24.7% of sexually initiated adolescents did not use a condom in their most recent sexual activity (22.9% of boys, 28.2% of girls), in spite of at the school environment 89.1% of them receiving orientation about STDs, 69.7% receiving orientation of where to acquire condoms for free (as part of a public health campaign from the Brazilian government) and 82.9% had heard of other forms of contraceptive methods.[16]

In Canada[සංස්කරණය]

One group of Canadian researchers found a relationship between self-esteem and sexual activity. They found that students, especially girls, who were verbally abused by teachers or rejected by their peers were more likely than other students to have sex by the end of the Grade 7. The researchers speculate that low self-esteem increases the likelihood of sexual activity: "low self-esteem seemed to explain the link between peer rejection and early sex. Girls with a poor self-image may see sex as a way to become 'popular', according to the researchers".[17]

In India[සංස්කරණය]

In India there is growing evidence that adolescents are becoming more sexually active. It is feared that this will lead to an increase in spread of HIV/AIDS among adolescents, increase the number of unwanted pregnancies and abortions, and give rise to conflict between contemporary social values. Adolescents have relatively poor access to health care and education. With cultural norms opposing extramarital sexual behavior "these implications may acquire threatening dimensions for the society and the nation".[18]

- Motivation and frequency

Sexual relationships outside marriage are not uncommon among teenage boys and girls in India. By far, the best predictor of whether or not a girl would be having sex is if her friends were engaging in the same activities. For those girls whose friends were having a physical relationship with a boy, 84.4% were engaging in the same behavior. Only 24.8% of girls whose friends were not having a physical relationship had one themselves. In urban areas, 25.2% of girls have had intercourse and in rural areas 20.9% have. Better indicators of whether or not girls were having sex were their employment and school status. Girls who were not attending school were 14.2% (17.4% v. 31.6%) more likely and girls who were employed were 14.4%(36.0% v. 21.6%) more likely to be having sex.[18]

In the Indian sociocultural milieu girls have less access to parental love, schools, opportunities for self-development and freedom of movement than boys do. It has been argued that they may rebel against this lack of access or seek out affection through physical relationships with boys. While the data reflects trends to support this theory, it is inconclusive.[18] The freedom to communicate with adolescent boys was restricted for girls regardless of whether they lived in an urban or rural setting, and regardless of whether they went to school or not. More urban girls than rural girls discussed sex with their friends. Those who did not may have felt "the subject of sexuality in itself is considered an 'adult issue' and a taboo or it may be that some respondents were wary of revealing such personal information."[19]

- Contraceptive use

Among Indian girls, "misconceptions about sex, sexuality and sexual health were large. However, adolescents having sex relationships were somewhat better informed about the sources of spread of STDs and HIV/AIDS."[18] While 40.0% of sexually active girls were aware that condoms could help prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS and reduce the likelihood of pregnancy, only 10.5% used a condom during the last time they had intercourse.[18]

In The Netherlands[සංස්කරණය]

According to Advocates for Youth, the United States' teen pregnancy rate is over four times as much as it is in the Netherlands.[20] In comparison, in the documentary, Let's Talk About Sex, a photographer named James Houston travels from Los Angeles to D.C. and to the Netherlands.[21] In the Netherlands, he contrasts European and American attitudes about sex. From the HIV rates to the contemplations of teen parenthood in America, Houston depicts a society in which America and the Netherlands differ.

Most Dutch parents practice vigilant leniency,[22] in which they have a strong familial bond and are open to letting their children make their own decisions.

Gezelligheid is a term used by many Dutch adolescents to describe their relationship with their family. The atmosphere is open and there is little that is not discussed between parents and children.

Amy Schalet, author of Not Under My Roof: Parents, Teens, and the Culture of Sex discusses in her book how the practices of Dutch parents strengthen their bonds with their children. Teenagers feel more comfortable about their sexuality and engage in discussion with their parents about it. A majority of Dutch parents feel comfortable allowing their teenagers to have their significant other spend the night.[23]

Sexually transmitted infections[සංස්කරණය]

Adolescents have the highest rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) when compared to older groups. Sexually active adolescents are more likely to believe that they will not contract a sexually transmitted infection than adults. Adolescents are more likely to have an infected partner and less likely to receive health care when an STI is suspected. They are also less likely to comply with the treatment for an STI. Coinfection is common among adolescents.[2]

An STI can have a large negative physiological and psychological effect on an adolescent. The goal of the pediatrician is for early diagnosis and treatment. Early treatment is important for preventing medical complications and infertility. Prevention of STIs should be a priority for all health care providers for adolescents. Diagnosis of an STI begins the evaluation of concomitant STIs and the notification and treatment of sexual partners. Some states in the US require the reporting of STIs to the state's health department.[2]

Media influence[සංස්කරණය]

Modern media contains more sexual messages than was true in the past and the effects on teen sexual behavior remain relatively unknown.[24] Only 9% of the sex scenes on 1,300 of cable network programming discusses and deals with the negative consequences of sexual behavior.[25] The Internet may further provide adolescents with poor information on health issues, sexuality, and sexual violence.[26]

A study on examining sexual messages in popular TV shows found that 2 out of 3 programs contained sexually related actions. 1 out of 15 shows included scenes of sexual intercourse itself. Shows featured a variety of sexual messages, including characters talking about when they wanted to have sex and how to use sex to keep a relationship alive. Some researchers believe that adolescents can use these messages as well as the sexual actions they see on TV in their own sexual lives.[27]

The results of a study by Deborah Tolman and her colleagues indicated that adolescent exposure to sexuality on television in general does not directly affect their sexual behaviors, rather it is the type of message they view that has the most impact.[28] What really affected adolescents was what type of societal gender stereotypes they were seeing enacted in the sexual scenes they saw on TV.

Girls felt they had less control over their sexuality when they saw men objectifying women and behaving as if commitment wasn’t important. The consequences of this kind of influence are not minuscule. Young girls become surrounded by women that influence sexual objectification and show that it is okay to be weak and answer to men all the time. However, girls who saw women on TV who refuted men’s sexual advances usually felt more comfortable talking about their own sexual needs in their sexual experiences as well as standing up for themselves. They were comfortable setting sexual limits and therefore held more control over their sexuality. Findings for boys were less clear; those who saw dominant and aggressive men actually had less sexual experiences. Perhaps there were less effects on boys because this Heterosexual Script does not affect them as deeply as it does girls.[28]

However some scholars have argued that such claims of media effects have been premature.[29] Furthermore, according to US government health statistics, teens have delayed the onset of sexual intercourse in recent years, despite increasingly amounts of sexual media.[30]

A 2008 study wanted to find out if there was any correlation between sexual content shown in the media and teenage pregnancy. Research showed that teens who viewed high levels of sexual content were twice as likely to get pregnant within three years compared to those teens who were not exposed to as much sexual content. The study concluded that the way media portrays sex has a huge effect on adolescent sexuality.[31]

Teenage pregnancy[සංස්කරණය]

Adolescent girls become fertile following the menarche (first menstrual period), which occurs in the United States at an average age of 12.5, although it can vary widely between different girls. After menarche, sexual intercourse (especially without contraception) can lead to pregnancy. The pregnant teenager may then miscarry, have an abortion, or carry the child to full term.

Pregnant teenagers face many of the same issues of childbirth as women in their 20s and 30s. However, there are additional medical concerns for younger mothers, particularly those under 15 and those living in developing countries; for example, obstetric fistula is a particular issue for very young mothers in poorer regions.[32] For mothers between 15 and 19, risks are associated more with socioeconomic factors than with the biological effects of age.[33] However, research has shown that the risk of low birth weight is connected to the biological age itself, as it was observed in teen births even after controlling for other risk factors (such as utilisation of antenatal care etc.).[34][35]

Worldwide, rates of teenage births range widely. For example, sub-Saharan Africa has a high proportion of teenage mothers whereas industrialized Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan have very low rates.[36] Teenage pregnancy in developed countries is usually outside of marriage, and carries a social stigma; teenage mothers and their children in developed countries show lower educational levels, higher rates of poverty, and other poorer "life outcomes" compared with older mothers and their children.[37] In the developing world, teenage pregnancy is usually within marriage and does not carry such a stigma.[38]

Legal aspects of adolescent sexual activity[සංස්කරණය]

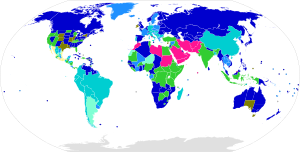

– puberty

– less than 12

– 12

– 13

– 14

– 15

– 16

– 17

– 18

– 19

– 20

– 21+

– varies by state/province/region/territory

– must be married

– no law

– no data available

Sexual conduct between adults and adolescents younger than the local age of consent is illegal, and in some Islamic countries any kind of sexual activity outside marriage is prohibited. In many jurisdictions, sexual intercourse between adolescents with a close age difference is not prohibited. Around the world, the average age-of-consent is 16,[39] but this varies from being age 12 in Angola, age 16 in Spain and Canada, and age 16-18 in the United States. In some jurisdictions, the age-of-consent for homosexual acts may be different from that for heterosexual acts. The age-of-consent in a particular jurisdiction is typically the same as the age of majority or several years younger. The age at which one can legally marry is also sometimes different from the legal age-of-consent.

Sexual relations with a person under the age-of-consent are generally a criminal offense in the jurisdiction in which the crime was committed, with punishments ranging from token fines to life imprisonment. Many different terms exist for the charges laid and include statutory rape, illegal carnal knowledge, or corruption of a minor. In some cases, sexual activity with someone above the legal age-of-consent but beneath the age of majority can be punishable under laws against contributing to the delinquency of a minor.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

Society’s influence on adolescent sexuality[සංස්කරණය]

Social constructionist perspective[සංස්කරණය]

The social constructionist perspective (see social constructionism for a general definition) on adolescent sexuality examines how power, culture, meaning and gender interact to affect the sexualities of adolescents.[40] This perspective is closely tied to feminist and queer theory. Those who believe in the social constructionist perspective state that the current meanings most people in our society tie to female and male sexuality are actually a social construction to keep heterosexual and privileged people in power.[41]

Researchers interested in exploring adolescent sexuality using this perspective typically investigates how gender, race, culture, socioeconomic status and sexual orientation affect how adolescent understand their own sexuality.[42] An example of how gender affects sexuality is when young adolescent girls state that they believe sex is a method used to maintain relationships when boys are emotionally unavailable. Because they are girls, they believe they ought to engage in sexual behavior in order to please their boyfriends.[43]

Developmental feminist perspective[සංස්කරණය]

The developmental feminist perspective is closely tied to the social constructionist perspective. It is specifically interested in how society's gender norms affect adolescent development, especially for girls. For example, some researchers on the topic hold the view that adolescent girls are still strongly affected by gender roles imposed on them by society and that this in turn affects their sexuality and sexual behavior. Deborah Tolman is an advocate for this viewpoint and states that societal pressures to be "good" cause girls to pay more attention to what they think others expect of them than looking within themselves to understand their own sexuality. Tolman states that young girls learn to objectify their own bodies and end up thinking of themselves as objects of desire. This causes them to often see their own bodies as others see it, which causes them to feel a sense of detachment from their bodies and their sexualities. Tolman calls this a process of disembodiment. This process leaves young girls unassertive about their own sexual desires and needs because they focus so much on what other people expect of them rather than on what they feel inside.[10]

Another way gender roles affect adolescent sexuality is thought the sexual double standard. This double standard occurs when others judge women for engaging in premarital sex and for embracing their sexualities, while men are rewarded for the same behavior.[44] It is a double standard because the genders are behaving similarly, but are being judged differently for their actions because of their gender. An example of this can be seen in Tolman’s research when she interviews girls about their experiences with their sexualities. In Tolman’s interviews, girls who sought sex because they desired it felt like they had to cover it up in order (for example, they blamed their sexual behavior on drinking) to not be judged by others in their school. They were afraid of being viewed negatively for enjoying their sexuality. Many girls were thus trying to make their own solutions (like blaming their sexual behavior on something else or silencing their own desires and choosing to not engage in sexual behavior) to a problem that is actually caused by power imbalances between the genders within our societies.[10] Other research showed that girls were tired of being judged for their sexual behavior because of their gender. However, even these girls were strongly affected by societal gender roles and rarely talked about their own desires and instead talked about how "being ready" (rather than experiencing desire) would determine their sexual encounters.[44]

O’Sullivan and her colleagues assessed 180 girls between the ages of 12 and 14 on their perceptions on what their first sexual encounters would be like; many girls reported feeling negative emotions towards sex before their first time. The researchers think this is because adolescent girls are taught that society views adolescent pre-marital sex in negative terms. When they reported positive feelings, the most commonly listed one was feeling attractive. This shows how many girls objectify their own bodies and often think about this before they think of their own sexual desires and needs.[45]

Researchers found that having an older sibling, especially an older brother, affected how girls viewed sex and sexuality.[46] Girls with older brothers held more traditional views about sexuality and said they were less interested in seeking sex, as well as less interested responding to the sexual advances of boys compared with girls with no older siblings. Researchers believe this is because older siblings model gender roles, so girls with older siblings (especially brothers) may have more traditional views of what society says girls and boys should be like; girls with older brothers may believe that sexual intercourse is mostly for having children, rather than for gaining sexual pleasure. This traditional view can inhibit them from focusing on their own sexualities and desires, and may keep them constrained to society’s prescribed gender roles.[46]

Social learning and the sexual self-concept[සංස්කරණය]

Developing a sexual self-concept is an important developmental step during adolescence. This is when adolescents try to make sense and organize their sexual experiences so that they understand the structures and underlying motivations for their sexual behavior.[47] This sexual self-concept helps adolescents organize their past experiences, but also gives them information to draw on for their current and future sexual thoughts and experiences. Sexual self-concept affects sexual behavior for both men and women, but it also affects relationship development for women.[47] Development of one’s sexual self-concept can occur even before sexual experiences begin.[48] An important part of sexual self-concept is sexual esteem, which includes how one evaluates their sexuality (including their thoughts, emotions and sexual activities).[49] Another aspect is sexual anxiety; this includes one’s negative evaluations of sex and sexuality.[49] Sexual self-concept is not only developed from sexual experiences; both girls and boys can learn from a variety of social interactions such as their family, sexual education programs, depictions in the media and from their friends and peers.[47][50] Girls with a positive self-schema are more likely to be liberal in their attitudes about sex, are more likely to view themselves as passionate and open to sexual experience and are more likely to rate sexual experiences as positive. Their views towards relationships show that they place high importance on romance, love and intimacy. Girls who have a more negative view often say they feel self-conscious about their sexuality and view sexual encounters more negatively. The sexual self-concept of girls with more negative views are highly influenced by other people; those of girls who hold more positive views are less so.[47]

Boys are less willing to state they have negative feelings about sex than girls when they describe their sexual self-schemas.[51] Boys are not divided into positive and negative sexual self-concepts; they are divided into schematic and non-schematic (a schema is a cluster of ideas about a process or aspect of the world; see schema). Boys who are sexually schematic are more sexually experienced, have higher levels of sexual arousal, and are more able to experience romantic feelings. Boys who are not schematic have fewer sexual partners, a smaller range of sexual experiences and are much less likely than schematic men to be in a romantic relationship.[51]

When comparing the sexual self-concepts of adolescent girls and boys, researchers found that boys experienced lower sexual self-esteem and higher sexual anxiety. The boys stated they were less able to refuse or resist sex at a greater rate than the girls reported having difficulty with this. The authors state that this may be because society places so much emphasis on teaching girls how to be resistant towards sex, that boys don’t learn these skills and are less able to use them when they want to say no to sex. They also explain how society’s stereotype that boys are always ready to desire sex and be aroused may contribute to the fact that many boys may not feel comfortable resisting sex, because it is something society tells them they should want.[52] Because society expects adolescent boys to be assertive, dominant and in control, they are limited in how they feel it is appropriate to act within a romantic relationship. Many boys feel lower self-esteem when they can’t attain these hyper-masculine ideals that society says they should. Additionally, there is not much guidance on how boys should act within relationships and many boys do not know how to retain their masculinity while being authentic and reciprocating affection in their relationships. This difficult dilemma is called the double-edged sword of masculinity by some researchers.[53]

Hensel and colleagues conducted a study with 387 female participants between the ages of 14 and 17 and found that as the girls got older (and learned more about their sexual self-concept), they experienced less anxiety, greater comfort with sexuality and experienced more instances of sexual activity.[50] Additionally, across the four years (from 14-17), sexual self-esteem increased, and sexual anxiety lessened. The researchers stated that this may indicate that the more sexual experiences the adolescent girls have had, the more confidence they hold in their sexual behavior and sexuality. Additionally, it may mean that for girls who have not yet had intercourse, they become more confident and ready to participate in an encounter for the first time.[54] Researchers state that these patterns indicate that adolescent sexual behavior is not at all sporadic and impulsive, rather that it is strongly affected by the adolescent girls’ sexual self-concept and changes and expands through time.[54]

Sex education[සංස්කරණය]

Sex education, also called "Sexuality Education" or informally "Sex Ed" is education about human sexual anatomy, sexual reproduction, sexual intercourse, human sexual behavior, and other aspects of sexuality, such as body image, sexual orientation, dating, and relationships. Common avenues for sex education are parents, caregivers, friends, school programs, religious groups, popular media, and public health campaigns.

Sexual education is not always taught the same in every country. For example, in France sex education has been part of school curricula since 1973. Schools are expected to provide 30 to 40 hours of sex education, and pass out condoms to students in grades eight and nine. In January, 2000, the French government launched an information campaign on contraception with TV and radio spots and the distribution of five million leaflets on contraception to high school students.[55]

In Germany, sex education has been part of school curricula since 1970. Since 1992 sex education is by law a governmental duty.[56] A survey by the World Health Organization concerning the habits of European teenagers in 2006 revealed that German teenagers care about contraception. The birth rate among German 15- to 19-year-olds is 11.7 per 1000 population, compared to 2.9 per 1000 population in Korea, and 55.6 per 1000 population in US.[57]

According to SIECUS, the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, in most families, parents are the primary sex educators of their adolescents. They found 93% of adults they surveyed support sexuality education in high school and 84% support it in junior high school.[58] In fact, 88% of parents of junior high school students and 80% of parents of high school students believe that sex education in school makes it easier for them to talk to their adolescents about sex.[59] Also, 92% of adolescents report that they want both to talk to their parents about sex and to have comprehensive in-school sex education.[තහවුරු කර නොමැත]

In America, not only do U.S. students receive sex education within school or religious programs, but they are also educated by their parents. American parents are less prone to influencing their children's actual sexual experiences than they are simply telling their children what they should not do. They promote abstinence while educating their children with things that may make their adolescents not want to engage in sexual activity.[60]

Almost all U.S. students receive some form of sex education at least once between grades 7 and 12; many schools begin addressing some topics as early as grade 5 or 6.[61] However, what students learn varies widely, because curriculum decisions are quite decentralized.[62] Two main forms of sex education are taught in American schools: comprehensive and abstinence-only. A 2002 study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 58% of secondary school principals describe their sex education curriculum as comprehensive, while 34% said their school's main message was abstinence-only.[62] The difference between these two approaches, and their impact on teen behavior, remains a controversial subject in the U.S.[63][64] Some studies have shown abstinence-only programs to have no positive effects.[65] Other studies have shown specific programs to result in more than 2/3 of students maintaining that they will remain abstinent until marriage months after completing such a program;[66] such virginity pledges, however, are statistically ineffective,[67][68] and over 95% of Americans do, in fact, have sex before marriage.[69]

In Asia the state of sex education programs are at various stages of development. Indonesia, Mongolia, South Korea and Sri Lanka have a systematic policy framework for teaching about sex within schools. Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand have assessed adolescent reproductive health needs with a view to developing adolescent-specific training, messages and materials. India has programs that specifically aim at school children at the age group of nine to sixteen years. These are included as subjects in the curriculum and generally involved open and frank interaction with the teachers. Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan have no coordinated sex education programs.[70]

Some educators hold the view that sexuality is equated with violence. These educators think that not talking about sexuality will decrease the rate of adolescent sexuality. However, not having access to sexual education has been found to have negative effects upon students, especially groups such as adolescent girls who come from low-income families. Not receiving appropriate sexual health education increases teenage pregnancy, sexual victimization and high school dropout rates. Researchers state that it is important to educate students about all aspects of sexuality and sexual health to reduce the risk of these issues.[71]

The view that sexuality is victimization teaches girls to be careful of being sexually victimized and taken advantage of. Educators who hold this perspective encourage sexual education, but focus on teaching girls how to say no, teaching them of the risks of being victims and educate them about risks and diseases of being sexually active. This perspective teaches adolescents that boys are predators and that girls are victims of sexual victimization. Researchers state that this perspective does not address the existence of desire within girls, does not address the societal variables that influence sexual violence and teaches girls to view sex as dangerous only before marriage. In reality, sexual violence can be very prevalent within marriages too.[71]

Another perspective includes the idea that sexuality is individual morality; this encourages girls to make their own decisions, as long as their decision is to say no to sex before marriage. This education encourages self-control and chastity.[71]

Lastly, the sexual education perspective of the discourse of desire is very rare in U.S. high schools.[40] This perspective encourages adolescents to learn more about their desires, gaining pleasure and feeling confident in their sexualities. Researchers state that this view would empower girls because it would place less emphasis on them as the victims and encourage them to have more control over their sexuality.[71]

Research on how gender stereotypes affect adolescent sexuality is important because researchers believe it can show sexual health educators how they can improve their programming to more accurately attend to the needs of adolescents. For example, studies have shown how the social constructed idea that girls are "supposed to" not be interested in sex have actually made it more difficult for girls to have their voices heard when they want to have safer sex.[72][73] At the same time, sexual educators continuously tell girls to make choices that will lead them to safer sex, but don’t always tell them ‘how’ they should go about doing this. Instances such as these show the difficulties that can arise from not exploring how society’s perspective of gender and sexuality affect adolescent sexuality.[74]

See also[සංස්කරණය]

- Adolescent sexuality in Canada

- Adolescent sexuality in the United Kingdom

- Adolescent sexuality in the United States

- Age disparity in sexual relationships

- Romeo and Juliet laws

- Child sexuality

- Condom

- Family planning

- Sexual ethics

References[සංස්කරණය]

- ↑ Feldman, Robert (2015). Discovering the life span. Boston: Pearson. ISBN 9780205992317.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Marcdante, Karen (2015). Nelson essentials of pediatrics. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 9781455759804: Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 De Gaston J. F.; Weed S. (1996). "Understanding gender differences in adolescent sexuality". Adolescence. 31 (121): 217–231. PMID 9173787.

- ↑ Ott M. A.; Pfeiffer E. J.; Fortenberry J. D. (2006). "Perceptions of Sexual Abstinence among High-Risk Early and Middle Adolescents". Journal of Adolescent Health. 39 (2): 192–198. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.009. PMID 16857530.

- ↑ Godeau E, Nic Gabhainn S, Vignes C, Ross J, Boyce W, Todd J (January 2008). "Contraceptive use by 15-year-old students at their last sexual intercourse: results from 24 countries". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162 (1): 66–73. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.8. PMID 18180415.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Amanda MacMillan / Health. com. "Your Birth Control Pill Might Raise Your Depression Risk". TIME.com. සම්ප්රවේශය 2016-10-05.

- ↑ Orenstein, Peggy (2016). Girls & sex : navigating the complicated new landscape. New York, NY: Harper, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. ISBN 9780062209726.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Carpenter L. M. (2002). "Gender and the meaning and experience of virginity loss in the contemporary United States". Gender and Society. 16: 345–365. doi:10.1177/0891243202016003005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 O'Sullivan Lucia; Majerovich JoAnn (2008). "Difficulties with sexual functioning in a sample of male and female late adolescent and young adult university students". The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 17 (3): 109–121. සැකිල්ල:Hdl.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Tolman, Deborah L. (2002). "Female adolescent sexuality: an argument for a developmental perspective on the new view of women's sexual problems". Women & Therapy. Taylor and Francis. 42 (1–2): 195–209. doi:10.1300/J015v24n01_21.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Waldner Haugrud; Macgruder B (1996). "Homosexual identity expression among lesbian and gay adolescents: An analysis of perceived structural associations". Youth & Society. 27: 313–333. doi:10.1177/0044118X96027003003.

- ↑ Diamond L (2000). "Sexual identity, attractions, and behavior among young sexual-minority women over a two-year period". Developmental Psychology. 36 (2): 241–250. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.241. PMID 10749081.

- ↑ Brazilians among those who lose virginity earliest සැකිල්ල:Pt icon

- ↑ Saúde em Movimento's Health Journal – 30% of Brazilian boys lose their virginity before age 15, Brazil leads ranking සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත ජනවාරි 14, 2014 at the Wayback Machine සැකිල්ල:Pt icon

- ↑ Época – The Brazilian through statistics සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine සැකිල්ල:Pt icon

- ↑ IBGE: 28.7% of students aged 13-15 said they already have lost their virginity – Terra Educação සැකිල්ල:Pt icon

- ↑ Peer rejection tied to early sex in pre-teens සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත ඔක්තෝබර් 11, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 R.S.Goya. "Socio-psychological Constructs of Premarital Sex Behavior among Adolescent Girls in India" (pdf). Abstract. Princeton University. සම්ප්රවේශය 2007-01-21.

- ↑ Dhoundiyal Manju; Venkatesh Renuka (2006). "Knowledge regarding human sexuality among adolescent girls". The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 73 (8): 743. doi:10.1007/BF02898460. PMID 16936373. 2007-09-28 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2017-01-09.

- ↑ සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත, http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/publications/publications-a-z/419-adolescent-sexual-health-in-europe-and-the-us, ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 2017-01-09

- ↑ සංරක්ෂිත පිටපත, http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/press-room/1811-lets-talk-about-sex-documentary-and-campaign-take-on-sexual-health-crisis, ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 2017-01-09

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Schalet, Amy (2011). Not Under My Roof: Parents, Teens, and the Culture of Sex. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Brown JD (February 2002). "Mass media influences on sexuality". J Sex Res. 39 (1): 42–5. doi:10.1080/00224490209552118. PMID 12476255.

- ↑ Pawlowski,Cheryl.,PH d. Glued to the Tube., Sourcebooks, INC., Naperville,Il.2000.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam, Kaveri., Greenfield, Patricia,M., Tynes, Brendesha. The Internet Influences Teen Sexual Attitudes. Teen Sexuality:Opposing Viewpoints 2006.

- ↑ Brown J. D. (2002). "Mass media influences on sexuality". The Journal of Sex Research. 39 (1): 42–45. doi:10.1080/00224490209552118. PMID 12476255.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Tolman DL, Kim JL, Schooler D, Sorsoli CL (January 2007). "Rethinking the associations between television viewing and adolescent sexuality development: bringing gender into focus". J Adolesc Health. 40 (1): 84.e9–16. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.002. PMID 17185211.

- ↑ Steinberg L, Monahan KC (November 2007). "Age differences in resistance to peer influence". Dev Psychol. 43 (6): 1531–43. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. PMC 2779518. PMID 18020830.

- ↑ childstats.gov

- ↑ Chandra, A., Martino, S. C., Collins, R. L., Elliott, M. N., Berry, S. H., Kanouse, D. E., & Miu, A. (2008). Does Watching Sex on Television Predict Teen Pregnancy? Findings From a National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Pediatrics, 122(5), 1047-1054. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3066.

- ↑ Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries

- ↑ Makinson C (1985). "The health consequences of teenage fertility". Fam Plann Perspect. 17 (3): 132–9. doi:10.2307/2135024. JSTOR 2135024. PMID 2431924.

- ↑ Loto, OM; Ezechi, OC; Kalu, BKE; Loto, Anthonia B; Ezechi, Lilian O; Ogunniyi, SO (2004). "Poor obstetric performance of teenagers: is it age- or quality of care-related?". Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 24 (4): 395–8. doi:10.1080/01443610410001685529. PMID 15203579.

- ↑ Abalkhail, BA (1995). "Adolescent pregnancy: Are there biological barriers for pregnancy outcomes?". The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association. 70 (5–6): 609–25. PMID 17214178.

- ↑ Indicator: Births per 1000 women (15–19 ys) – 2002 සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත ජූලි 13, 2007 at the Wayback Machine UNFPA, State of World Population 2003, Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ↑ The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. (2002). "Not Just Another Single Issue: Teen Pregnancy Prevention's Link to Other Critical Social Issues" (PDF). (58.5 KB). Retrieved May 27, 2006.

- ↑ Population Council (January 2006). "Unexplored Elements of Adolescence in the Developing World". Population Briefs. 12 (1). 2007-08-14 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2017-01-09.

- ↑ http://www.avert.org/age-of-consent.htm

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Tolman D. L.; Diamond L. M. (2001). "Desegregating sexuality research: Cultural and biological perspectives on gender and desire". Annual Review of Sex Research. 12: 33–74. PMID 12666736.

- ↑ Kitzinger, C., & Wilkinson, S. (1993). Theorizing heterosexuality. In S. Wilkinson & C. Kitzinger, (Eds.), Heterosexuality: A feminism and psychology reader (pp. 1-32). London: Sage Publications

- ↑ Tolman D. L.; Striepe M. I.; Harmon T. (2003). "Gender Matters: Constructing a Model of Adolescent Sexual Health". Journal of sex research. 40 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1080/00224490309552162. PMID 12806527.

- ↑ O'Sullivan L.; Meyer-Bahlburg H. F. L. (1996). "African-American and Latina inner-city girls' reports of romantic and sexual development". Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 20 (2): 221–238. doi:10.1177/02654075030202006.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Jackson S. M.; Cram F. (2003). "Disrupting the sexual double standard: young women's talk about heterosexuality". British Journal of Social Psychology. 42 (Pt 1): 113–127. doi:10.1348/014466603763276153. PMID 12713759.

- ↑ O'Sullivan L.; Hear K. D. (2008). "Predicting first intercourse among urban early adolescent girls: The role of emotions". Cognition and Emotion. 22 (1): 168–179. doi:10.1080/02699930701298465.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Kornreich J. L.; Hearn K. D.; Rodriguez G.; O'Sullivan L. F. (2003). "Sibling Influence, Gender Roles, and the Sexual Socialization of Unban Early Adolescent Girls". Journal of Sex Research. 40 (1): 101–110. doi:10.1080/00224490309552170. PMID 12806535.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Andersen B. L.; Cyranowski J. M. (1994). "Women's sexual self-schema". Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 67 (6): 1079–1100. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1079.

- ↑ Butler T. H.; Miller K. S.; Holtgrave D. R.; Forehand R.; Long N. (2006). "Stages of sexual readiness and six-month stage progression among African American pre-teens". Journal of Sex Research. 43 (4): 378–386. doi:10.1080/00224490609552337. PMID 17599259.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Snell, W. E. (1998). The multidimensional sexual self-concept questionnaire. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.),Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 521–524). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Hensel D. J.; Fortenberry J. D.; O'Sullivan L. F.; Orr D. P. (2011). "The developmental association of sexual self-concept with sexual behavior among adolescent women". Journal of Adolescence. 34 (4): 675–684. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.005. PMID 20970178.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Andersen B. L.; Cyranowski J. M.; Espindle D. (1999). "Men's sexual self-schema". Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 76 (4): 645–661. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.645.

- ↑ Dekhtyar O.; Cupp P.; Anderman E. (2008). "Sexual self-concept and sexual self-efficacy in adolescents: a possible clue to promoting sexual health?". Journal of Sex Research. 45 (3): 277–286. doi:10.1080/00224490802204480. PMID 18686156.

- ↑ Chu J. Y.; Porche M. V.; Tolman D. L. (2005). "The adolescent masculinity ideology in relationships scale: Development and validation of a new measure for boys". Men and Masculinities. 8: 93–115. doi:10.1177/1097184X03257453.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 O'Sullivan L. F.; Brooks-Gunn J. (2005). "The timing of changes in girls' sexual cognitions and behaviors in early adolescence: a prospective, cohort study". Journal of Adolescent Health. 37 (3): 211–219. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.019. PMID 16109340.

- ↑ Britain: Sex Education Under Fire UNESCO Courier

- ↑ Sexualaufklärung in Europa (German)

- ↑ http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/repcard3e.pdf

- ↑ SIECUS Report of Public Support of Sexuality Education(1999)SIECUS Report Online සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත දෙසැම්බර් 19, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Sex Education in America. (Washington, DC: National Public Radio, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, and Kennedy School of Government, 2004), p. 5.

- ↑ Schalet, Amy (2011). Not Under My Roof: Parents, Teens, and the Culture of Sex. The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Landry DJ, Singh S, Darroch JE (2000). "Sexuality education in fifth and sixth grades in U.S. public schools, 1999". Fam Plann Perspect. 32 (5): 212–9. doi:10.2307/2648174. PMID 11030258.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Sex Education in the U.S.: Policy and Politics" (PDF). Issue Update. Kaiser Family Foundation. October 2002. 2005-11-27 දින මුල් පිටපත (PDF) වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2007-05-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Hauser, Debra (2004). "Five Years of Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Education: Assessing the Impact". Advocates for Youth. 28 May 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2007-05-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ "Mathematica Findings Too Narrow" (Press release). National Abstinence Education Association. 2007-04-13. 17 May 2007 දින මුල් පිටපත වෙතින් සංරක්ෂණය කරන ලදී. සම්ප්රවේශය 2007-05-25.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ↑ Report: Abstinence Not Curbing Teen Sex[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Why Know Says They Are Effective In Increasing Teen Abstinence, http://www.chattanoogan.com/articles/article_116666.asp, ප්රතිෂ්ඨාපනය 2017-01-09

- ↑ Bearman PS, Brückner H (2001). "Promising the future: virginity pledges and first intercourse". American Journal of Sociology. 106 (4): 859–912. doi:10.1086/320295.

- ↑ Brückner H, Bearman P (April 2005). "After the promise: the STD consequences of adolescent virginity pledges". J Adolesc Health. 36 (4): 271–8. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.01.005. PMID 15780782.

- ↑ Finer LB (2007). "Trends in premarital sex in the United States, 1954–2003". Public Health Rep. 122 (1): 73–8. PMC 1802108. PMID 17236611.

- ↑ Adolescents In Changing Times: Issues And Perspectives For Adolescent Reproductive Health In The ESCAP Region සංරක්ෂණය කළ පිටපත 2012-02-11 at the Wayback Machine United Nations Social and Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 Fine M (1988). "Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: the missing discourse of desire". Harvard Educational Review. 58 (1): 29–53.

- ↑ Holland J.; Ramazanoglu C.; Scott S.; Sharpe S.; Thompson R. (1992). "Risk, power and the possibility of pleasure: Young women and safe sex". AIDS Care. 4 (3): 273–283. doi:10.1080/09540129208253099. PMID 1525200.

- ↑ Thompson, SR. & Holland, J. (1994). Younger women and safer (hetero)sex: Context, constraints and strategies, In C. Kitzinger & S. Wilkinson (Eds.), Women and health: Feminist perspectives. London: Falmer

- ↑ Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Scott, S., Sharpe, S., & Thompson, R. (1994). Sex, gender and power: young women’s sexuality in the shadow of AIDS. In B. Rauth (Ed.), AIDS: Reading on a global crisis. London: Allyn and Bacon.